Today, July 17, marks the anniversary of one of the darkest moments in Baptist history. But as with so many events in the Christian saga, God worked with those who love God to turn darkness into light and to redeem beauty from ashes.

On July 17, 1990, the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee gathered in Nashville for a called meeting to fire the leaders of Baptist Press. BP Director Al Shackleford and News Editor Dan Martin first refused to turn the SBC’s respected news service into a public relations office and then refused to resign. So, the Executive Committee fired them.

This is a historical story, but it’s also a personal story. Until about a month previously, I worked alongside Martin and Shackleford as a BP editor. I covered their firing as the editor of the Western Recorder, then the Kentucky Baptist Convention’s newspaper.

On that muggy summer afternoon, Martin and Shackleford became early martyrs in the crusade to turn the historically conservative Southern Baptist Convention far to the right. The “Baptist Holy War” began years before. It pitted the insurgents (who preferred to call themselves “conservatives” but also bore the labels “fundamental-conservatives” and, by the other side, “fundamentalists”) against the establishment (who likewise preferred to be called “conservatives” but bore the labels “moderates,” “moderate-conservatives” and, by the other side, “liberals.”)

The insurgents framed the challenge as a battle for the Bible, which they claimed is literal, transcribed word-for-word from God. The SBC’s six seminaries, which taught preachers how to interpret, proclaim and apply the Bible, received the focus of attention. The insurgents accused the seminaries of “liberalism,” while their defenders noted their orthodoxy and general right-of-center position within Christianity.

But because the SBC’s schism was political, the media got its share of attention, too. For almost four decades, BP had been charged with covering the SBC, both for its string of state newspapers, but for the secular media, as well. Across those years, BP earned the respect of editors and reporters across the country, who depended upon the news service to cover “the nation’s largest non-Catholic religious body.”

As journalists, our job was exhilarating. We covered one of the biggest religion stories of the 20th century — the struggle for the future of the SBC. Through the state papers and the hundreds of daily and weekly newspapers who received BP, our readers numbered in the millions. We covered news that truly mattered and a historic clash of ideas.

As Baptists, our job was heartbreaking. We sat in rooms and heard saints vilified. We watched the SBC — our denominational home — falling apart before our eyes.

As denominational workers, our job was perilous. Shackleford received verbal abuse practically every week from partisans who wanted the stories we wrote to reflect their — and only their — perspectives. The Executive Committee’s president, our boss, received intense pressure, particularly from the insurgents, to fire us.

“Everybody claims they want a free press. But what most people really want is an advocate.”

As Martin often said: “Everybody claims they want a free press. But what most people really want is an advocate.”

Over and over, Baptists told us they wanted us to be fair. But as the insurgents’ proportion of Executive Committee members steadily increased, they made it clear they wanted Baptist Press to advocate for their cause and to castigate the other side.

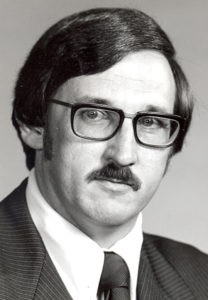

Dan Martin (Photo courtesy of Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives, Nashville, Tenn.)

Let me say straight up: I’ve never known, much less worked with, two people more honest, ethical and committed to fairness than Dan Martin and Al Shackleford. As we wrote articles about contentious issues, we balanced ideas and presenters: If someone on one side took a position on an issue, we found someone of equal “ranking” from the other side to explain the alternate perspective. Beyond that, we gave each side an equal number of paragraphs with an approximately equal number of lines.

This word-counting-as-fairness approach to journalism produced balanced articles. Unfortunately, they sometimes lacked nuance. And they certainly lacked the context we could have provided to such highly complicated issues. Back then, any explanation of context was deemed opinion. If sentences and paragraphs did not provide attribution to Baptist sources, we left them out.

“The new leaders of the Executive Committee proved they never wanted a fair news organization. They wanted someone to spin news their way, to make them look good.”

As it turned out, all this didn’t matter. In the New Orleans Superdome in June of 1990, the insurgents’ weakest-ever presidential candidate, Morris Chapman, defeated the other side’s strongest-ever candidate, Daniel Vestal. Simultaneously, thanks to presidential wins the previous 11 consecutive years, the SBC nominating system finally gave the insurgents a clear majority on the Executive Committee.

The next month, its leaders told Martin and Shackleford to resign. They declined. Then the committee convened and fired them. The new leaders of the Executive Committee proved they never wanted a fair news organization. They wanted someone to spin news their way, to make them look good.

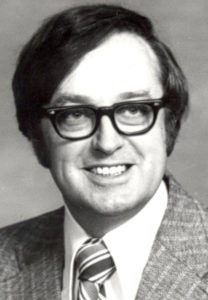

Al Shackleford (Photo courtesy of Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives, Nashville, Tenn.)

Al Shackleford worked at odd jobs for a couple of years before he accepted the editorship of Mature Living magazine at the SBC’s Sunday School Board. He held the position eight years until he died in a car accident almost a decade after his firing, July 23, 2000.

Baptists suffered a major loss with the firing of Martin at age 51. He was the best Baptist reporter of his generation and one of the best reporters in the United States in the latter half of the 20th century. One can only imagine the articles he would have written across another decade or two in Baptist life. Later, he used his abundant gifts generously — as a journalism professor, pastor, anti-gambling advocate and hospice chaplain. Now retired, he lives in the Dallas area.

Martin and Shackleford paid a huge price for their commitment to truth-telling and integrity. Other Baptists received residual blessings out of their sacrifice.

Shortly after their firing, a group of Baptists met in Atlanta to talk about what to do next, now that they felt cast out of the SBC. They grieved the indignities heaped upon revered seminary professors and worried about the fate of beloved missionaries. They also felt rage at the treatment of Martin and Shackleford. All this prompted them to launch the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, which will celebrate its 30th anniversary next summer.

But on the day of the firing, a group of journalists and other concerned Baptists announced formation of Associated Baptist Press, an independent news service by and for Baptists. Martin sealed its DNA for trustworthiness and independence as its interim founding editor.

Across the years, ABP faced its share of challenges — always needing more money, also processing churning change in mass media, church life and denominationalism — but it has remained free and independent. As a testimony to which side more favored a strong, independent press, ABP has not had to contend with external control issues and has not been considered a spinner of news. ABP merged with the Religious Herald of Virginia in 2013 to become Baptist News Global. Although the name has changed, the organization celebrates its 30th anniversary today, on the sad occasion of Martin’s and Shackleford’s firing.

Thank God for the lives and legacy of Dan Martin and Al Shackleford. And thank God for the historic freedom and promising future of Baptist News Global.

Marv Knox was a Baptist journalist for nearly 40 years, including editorships at the Western Recorder in Kentucky and Baptist Standard in Texas. Today, he leads Fellowship Southwest, a missions and ministry collaborative.

BNG’s board of directors invites readers to join them in making anniversary gifts to the news service’s Annual Fund. Today, your gift will be matched dollar-for-dollar by board member gifts. Give online at our Anniversary Page.