Daniel Bonnell is a contemplative artist who infuses biblical stories with new light. Because of what he sees as the ambiguity in the current moment, he has started painting on paper grocery bags to symbolize poverty of spirit conveying the sacred.

He earned a bachelor of fine arts degree from the Atlanta College of Art and a master of fine arts degree from the Savannah College of Art and Design. His post-graduate studies included classes with photographers Ansel Adams and Ed Ross, as well as the iconic graphic designer Milton Glaser.

Daniel Bonnell

In 2018, Bonnell won the prestigious Brother Nathan Cochran Award in Sacred Arts. His paintings hang in churches and cathedrals all over the world, and his art has appeared in publications in more than 100 countries and 30 languages. Many of his finest works may be viewed on his website.

Would you share any early memories about when you first became interested in art?

One special memory immediately comes to mind. When I was 9 years old, my parents took me to the 1964 New York World’s Fair. I will never forget how I felt when we rode the moving sidewalk into a building there. We first passed through a completely dark room and then suddenly found ourselves in the next room facing Michelangelo’s illuminated “Pieta” – which shows Mary holding the crucified body of Christ. That made quite an impression on my young soul and spirit.

Have you always focused on producing only sacred art images in your work or did you decide to solely concentrate on this specific field at some distinct point in your lengthy career?

Beginning in 1997, I chose to only paint sacred works so that I can be more focused on what I am as an individual artist — and most importantly — as a follower of the teachings of Jesus.

Would you describe how you often prepare yourself to begin a new drawing or painting?

I will first often read a devotion or spend time meditating over a few specific verses of Scripture. I will then sit there in front of a blank canvas, just waiting — sometimes for hours.

That must require great patience.

Well, I just pray and wait for inspiration. Back during the earliest times in my career, I would also sometimes sit there and repent about anything I knew I needed to change in my life. It was really about confession. After all, how could I expect anything holy to come through if I did not do that first?

“I also had to learn that when you try to create it is perfectly OK if you fail.”

So, you were trying to empty yourself first before beginning?

Yes. And then the work seemed to flow rather easily. Of course, I also had to learn that when you try to create it is perfectly OK if you fail. It is all part of a pilgrimage. And we do not have to be afraid if we fail at what we are trying to do.

You have commented in past articles about your use of ambiguity in many of your paintings. Can you explain that concept a bit more?

Ambiguity holds opposites together. The cross is a symbol of ambiguity in that it holds the suffering of Christ as well as the love of Christ. Even the two thieves on each side of Jesus were opposites, one cursing Jesus, the other hailing him as a king. I embrace ambiguity in multiple ways. The most obvious use of ambiguity is that I now paint on grocery bag paper as a sign of poverty of spirit even though the subject matter is sacred.

“The Holy Family” by Daniel Bonnell

Your paintings seem to convey many layers of meaning and really pull people in to study them more closely. Could you reference a few of the images a viewer might not readily see upon first viewing your painting titled “The Holy Family”?

Well, I am a symbolist artist. That means that I work out of my head, not from models or any imagery except what my mind’s eye gives me. I am also a symbolist artist in that there are many embedded symbols in my work that represent important dynamics of the narrative. Parables do the same thing.

In this painting called “The Holy Family,” you may not first see where the little boy Jesus appears. Look closely: he is standing right in front of his father, Joseph, and his mother, Mary, who is pregnant with James. He is reacting to you, the viewer, approaching them. He is trying to protect them like many young children might by spreading out his arms in front of them.

Another image you may not readily see unless you enlarge the painting is that young Jesus is facing a shadow in front of him — the crucifixion. Other symbols also await your discovery.

Your paintings and drawings often reveal a deep awareness of human suffering. Could you share the other early memory you mentioned from age 9 – just prior to this interview starting?

Yes. While I was in New York visiting the 1964 World’s Fair at age 9, my parents happened to drive along Houston Street. As we crossed by Bowery Street in Lower Manhattan, I looked over at a sidewalk and saw a man lying face down. He was not moving — and no one was attempting to help him. For me, that was very traumatizing. I could not understand why no one was helping him. And when I looked farther down the street, I could see other men just like him. That stayed in my subconscious for many years, just like the image of “The Pieta.”

You then did something very remarkable in response to those images, when you were just 24 years old. Could you share that here? You surely saw a lot of suffering during that period of service.

Well, I decided to just give up my apartment in a different part of the country and move to New York City. I did not know anyone there and I wanted to serve others by working at the Bowery Mission. I moved in and volunteered there for about two-and-a-half years. They had a 90-day program to help alcoholics recover and a soup kitchen. Jesus came to serve, not to be served. Apart from all I learned — and I was still quite naive then — I met my wife there when she came in to do some volunteer work.

“They did not really care about my title as their teacher; they just wanted to know that I loved them.”

So, you learned quite a bit about human suffering then and much later during your life while teaching art to inner city teens, right?

Yes, they taught me so many things. Many of those kids in Savannah were descended from the slave culture. Like their parents, they have known much poverty and suffering. Yet they often display so much thankfulness and contentment with whatever they have. And they really know how to be fully present in the moment. They did not really care about my title as their teacher; they just wanted to know that I loved them.

Those students also changed my theology. You cannot teach them sanctification because they have already been sanctified. I believe they are a millennium ahead of us in many ways.

Returning now to your personal approach to your work, would you also describe how you experience each painting or drawing while you are completing it or once you have finished it?

Well, I always like to say that each painting is a personal devotion — or a phone call home to my Heavenly Father. My art is also about being embraced; we are all first embraced by love in the womb and then we spend our lives trying to get back to the womb. We are all just spirits having a bodily experience.

Besides love, what other feelings or emotions are you trying to directly convey in your work, or do they simply come forth on their own?

What artists do, if they are aware of what they need to do, is they must channel creativity from a source. Non-Christians would say that they are channeling creativity from the ground of being. The Christian would refer to the source as the Holy Spirit.

Yet to channel creativity, you must first put away your false self. Only then can you get out of the way of the creative gifts that await you. In other words, that is when you can begin channeling love, compassion and all the other gifts that the Holy Spirit seeks to give you. And you will often find out that the gifts know much more than you do.

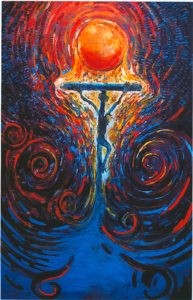

“The Beautiful Mess” by Daniel Bonnell

Would you offer a few reflections on two very colorful paintings, “The Road to Emmaus” and “The Beautiful Mess”?

Well, in “The Road to Emmaus,” the sky is the symbol for God the Father fully embracing his Son, Jesus, who is walking along the road with two disciples.

As for “The Beautiful Mess,” we see great ambiguity there. God is raining down a myriad of bright and joyful colors of love and compassion, yet all that beauty is happening within the context of watching his much-beloved son, Jesus, die on the cross. It is great beauty happening within deep pain. You can also say that right now during the pandemic, every day is a beautiful mess — yet it is all part of the mystery of God’s love.