Why Donald Trump? Why are American evangelicals so enamored of a president who could serve as a poster boy for the seven deadly sins?

Simple hypocrisy is the simplest answer. Others see evangelical support for Trump as nothing more than transactional politics.

Simple hypocrisy is the simplest answer. Others see evangelical support for Trump as nothing more than transactional politics.

Kristen Kobes Du Mez, a history professor at Calvin College, isn’t buying either of these explanations. In Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, she explains why. The majority of white American evangelicals support Trump, she says, because he embodies the kind of militant masculinity they have learned to love.

Du Mez’s first hint that a radical shift had taken place in the world of white American evangelicalism came when students directed her attention to John Eldredge’s Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man’s Soul. First published in 2001, the book sold more than 4 million copies in the United States alone. Men are brimming with testosterone, Eldredge explained, because God needs warriors. Men are dangerous, unpredictable, combative and aggressively sexual — characteristics that fitted them for lives of adventure and leadership. Instead of repenting of these traits, Eldredge said, Christian men should embrace them.

In 2015, as she watched evangelicals lining up behind the strutting embodiment of the militant masculinity celebrated in Eldredge’s book, Du Mez decided to take a closer look.

I first became aware of Du Mez’s project shortly after writing a piece for Baptist News Global in October of 2016 called Jesus and John Wayne: Must we choose? When I Googled “Jesus and John Wayne,” the first item up was a 1980s song by that title by the Gaither Vocal Band that portrayed American evangelicals as living in a healthy tension between the fierce masculinity of John Wayne and the radical grace of Jesus. Evangelical enthusiasm for Donald Trump, I argued, suggested that that militant masculinity of John Wayne had eclipsed the spirituality of Jesus.

I first became aware of Du Mez’s project shortly after writing a piece for Baptist News Global in October of 2016 called Jesus and John Wayne: Must we choose? When I Googled “Jesus and John Wayne,” the first item up was a 1980s song by that title by the Gaither Vocal Band that portrayed American evangelicals as living in a healthy tension between the fierce masculinity of John Wayne and the radical grace of Jesus. Evangelical enthusiasm for Donald Trump, I argued, suggested that that militant masculinity of John Wayne had eclipsed the spirituality of Jesus.

Du Mez came across my article because she was thinking along similar lines. Her book includes a couple of references to my article and uses one of my best lines as a chapter title: “The unspoken mantra of post-war evangelicalism was simple: Jesus can save your soul, but John Wayne will save your ass.”

“Since the 1960s,” Du Mez notes, “male blue-collar work such as construction, manufacturing and agriculture had been in decline” while sectors open to educated women “such as health care, retail, education, finance and food service” were rapidly expanding. At the same time, “American culture still associated masculinity with working-class jobs.” By the 1970s, American men were in the throes of an identity crisis.

Saying ‘no’ to the 1960s

The militant masculinity described in Jesus and John Wayne is organically related to what scholars now call “white Christian nationalism.” Evangelicals had been on a roll in the wake of the Second World War with new churches springing up everywhere and liberals and conservative Christians agreeing that God had given America a leadership role to play in the world. America was great, it was widely believed, because America was good.

But in the 1960s, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement and second-wave feminism shattered American confidence. If the country was as imperialist, racist and misogynistic as her critics were claiming, the “goodness” of America was cast in doubt.

While Protestant mainline churches wrestled with issues of race, gender and imperialism, evangelicals, with few exceptions, clung to the myth of white Christian nationalism. Because racism was a personal and spiritual failing, the solution lay with the Christian gospel, not public policy.

Activist Phyllis Schafly wearing a “Stop ERA” badge, demonstrating with other women against the Equal Rights Amendment in front of the White House, Washington, D.C.

America’s anti-communist crusade was ordained of God and therefore noble. The quagmire of Vietnam simply indicated that America’s latest crop of young men had gone soft.

Most significant for Du Mez’s thesis, evangelicals charged that the feminist call for equal rights was a tacit rejection of biblical revelation. God created men and women with complementary, but very different, emotional attributes. Men and women were different, evangelicals typically argued, because they were built for distinct vocations.

Du Mez acknowledges that a small but valiant evangelical left has been wrestling with racism, sexism and imperialism for half a century; but she regards this movement as a minority report within the larger evangelical world. The prevailing evangelical response to these challenges has been to double down on white Christian nationalism.

In 1972, Phyllis Schlafly launched her crusade against the Equal Rights Amendment by insisting that “the very notion of women’s oppression was ludicrous.”

Meanwhile, Marabel Morgan sold 10 million copies of The Total Woman, an account of how she revived a troubled marriage by transforming herself into a submissive servant-temptress. Morgan introduced a “model of masculinity” in which “to be a man was to have a fragile ego and a vigorous libido. Men were entitled to lead, to rule and to have their needs met — all their needs, on their terms.”

A military model of family life

Next, Du Mez moves to Bill “chain-of-command” Gothard, a controversial figure who established the intellectual foundation on which others would build. Gothard channeled the Christian Reconstructionist thinking of Rousas John Rushdoony, a brooding, cantankerous writer who characterized the Civil War as “a religious war in which the South was defending Christian civilization.” Rushdoony, Du Mez later explains, took his leading ideas from Robert Lewis Dabney, the 19th century Southern Presbyterian scholar who supplied a theological justification for slavery.

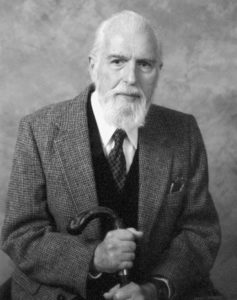

R.J. Rushdoony

The only answer to the problems facing America, in Rushdoony’s view, was the imposition of Old Testament law. “At the heart of this project,” Du Mez argues, “was the assertion of hierarchical authority.”

Drawing on Rushdoony, Gothard taught that God used natural hierarchies to regulate life. Wives must submit to husbands, children must submit to their parents, and employees must submit to employers. “In this way,” Du Mez says, “proponents of ‘biblical law’ married ‘traditional’ gender roles to unrestrained, free-market capitalism.”

Gothard’s hierarchical philosophy ordered Christian marriage on a military model in which “a wife owed her husband total submission, requiring approval for even the smallest household decisions.”

In 1970, child psychologist James Dobson offered a more palatable patriarchal vision in his influential book, Dare to Discipline. The authoritarian contours of Dobson’s philosophy would become increasingly apparent over time. The explicitly military cast of his thinking became more apparent once he moved his Focus on the Family enterprise from Pasadena, Calif., to Colorado Springs, Colo., in 1991. Like megachurch pastor Ted Haggard, Dobson exported his patriarchal theology into the American military using the Air Force Academy north of town as a Trojan horse.

“What started as a backlash against hippies, antiwar protestors, civil rights activists and urban minorities, evolved into a veneration of law enforcement and the military.”

“Meanwhile,” Du Mez asserts, “military men were refashioning Christianity in their own image, and offering their own brand of militant evangelicalism for broader consumption.” Soon military men like Oliver North and Jerry Boykin were emerging as Christian exemplars.

“With evangelicals in the vanguard, Americans had come to see the military as a bastion of ‘traditional values and old-fashioned virtue,’” Du Mez suggests. “Within this genre, real-life military warriors continued to bring an aura of authenticity that mere pastors couldn’t match.”

And if warriors were being valorized, the traditional “war is hell” mantra began to fade. “If the military was a source of virtue,” Du Mez says, “war, too, attained a moral bearing — even preemptive war.”

“What started as a backlash against hippies, antiwar protestors, civil rights activists and urban minorities,” in other words, “evolved into a veneration of law enforcement and the military.”

It’s a man’s world

Du Mez notes that the heroes venerated by the cult of militant masculinity were much more likely to be drawn from Hollywood, pop culture and current events than from the Bible. John Wayne, Teddy Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, Oliver North, Douglas MacArthur and George Patton were frequently held up as exemplars. When Mel Gibson’s Braveheart was released in 1995, William Wallace, the movie’s hero, was embraced as the prototypical Christian warrior.

The “purity culture” that took the evangelical world by storm in the 1980s and 1990s defined the role God had in mind for girls and women. Christian girls were to remain pure, “saving themselves for marriage” and ensuring that they did not create temptations for men. According to Eldridge’s Wild at Heart, “a woman sinned when she tried to control her world, when she was grasping rather than vulnerable, when she sought to control her own adventure rather than share in the adventure of a man.”

Men and women who kept themselves pure until marriage, the reasoning went, would be rewarded with what one writer called “mind-blowing sex.” Wives also could expect the protection of a godly husband.

The evangelical aversion to the LGBTQ movement flows from the same logic. Same-sex attraction isn’t part of God’s plan and therefore constitutes rebellion against the revealed will of God.

Du Mez argues that “over time, a common commitment to patriarchal power began to define the boundaries of the evangelical movement itself, as those who ran afoul of these orthodoxies quickly discovered.” When Russell Moore announced as a never-Trumper, he was forced to embark on a post-election “apology tour” in order to keep his job as president of the Southern Baptists Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

Shifts in biblical interpretation

The subheading of Jesus and John Wayne suggests that the cult of militant masculinity “corrupted” American evangelicalism. Du Mez identifies three ways in which a renewed focus on patriarchy shifted the focus of a faith.

Kristen Kobes Du Mez

First, references to pop culture and American political and military history abound in the body of literature she is describing, while biblical references recede into the background.

Second, when the Bible is quoted, the erotic poetry of Song of Songs and the violent visions of Revelation receive outsized attention. Song of Songs is used to justify the frequent allusions to testosterone-driven male sexuality found in this literature. The visions of Revelation demonstrate how “the suffering Messiah turned into the conquering Messiah.” New Calvinist pastor Mark Driscoll captured the tenor of the movement when he argued that “Jesus was a hero, not a loser, an Ultimate Fighter warrior king with a tattoo down his leg who rides into battle against Satan, sin and death on a trusty horse.” Tim LaHaye’s wildly successful Left Behind series, Du Mez points out, “ends in a violent bloodbath ushered in by Christ himself.”

Third, Du Mez argues, traditional virtues such as the fruit of the spirit and the Sermon on the Mount are either overtly rejected by these authors or categorized as “feminine virtues that don’t apply to men.”

The right enemies

Du Mez notes how the shifting fortunes of American politics and foreign policy influenced evangelical teaching. On the whole, she says, conservative evangelicalism flourished when the White House was in the hands of a Bill Clinton or a Barack Obama and floundered somewhat during the Reagan and two Bush administrations.

As Religious Right organizer Ralph Reed once said: “Part of politics is having the right friends, but an important part of politics is having the right enemies.” For decades, evangelicals had used communism as “the right enemy,” but with the collapse of Soviet Communism that became problematic. The Promise Keepers, a movement which Du Mez discusses at length, provided a softer version of evangelical patriarchy than Dobson and Gothard represented. Marital submission was seen as mutual and the responsibilities of Christian fatherhood, as opposed to male prerogatives, were emphasized.

The Promise Keepers even experimented cautiously with racial reconciliation, inviting Black preachers like Tony Evans and E.V. Hill to address their overwhelmingly white mass rallies. They even asked civil rights icon John Perkins to provide a critique of white evangelical racism in a widely distributed publication. But as Bill McCartney, the retired football coach who sparked the movement, has admitted, few white participants were ready to address the subject of race.

This experiment with soft patriarchy ended with 9/11. The communist boogie man was quickly replaced by the Islamist terrorism, and charlatans like Ergun and Emir Caner, Walid Shoebat, Zachariah Anani and Kamal Saleem were soon marketing themselves as Islamic terrorists redeemed by the blood of the Lamb. Long after the distortions and misrepresentations perpetrated by these imposters had been thoroughly vetted, they were still featured speakers at evangelical churches and conferences.

“Were evangelicals embracing an increasingly militant faith in response to a new threat from the Islamic world?” Du Mez asks. “Or were they creating the perception of threat to justify their own militancy and enhance their own power?” The question answers itself.

“Invariably,” Du Mez observes, “the heroic Christian man was a white man, and not infrequently a white man who defended against the threat of nonwhite men and foreigners.” God’s call to “wild, militant masculinity” was not extended to Black, Middle Eastern or Hispanic men. “Their aggression,” she writes, “is seen as dangerous, a threat to the stability of home and nation.”

The fringe goes mainstream

Du Mez anticipates the obvious critique that she is mistaking a fringe element for normative evangelicalism. The brand of militant masculinity described in Jesus and John Wayne may exist in some quarters, critics will argue, but American evangelicalism is too theologically and sociologically diverse to be reduced to white Christian nationalism and militant masculinity.

Du Mez admits that men like Rushdoony and Gothard were initially viewed as fringe actors within the American evangelicalism. But evangelical opinion leaders almost never got into trouble for pushing the envelope on patriarchy. Only for those deemed too inclusive did danger lurk. “As militant masculinity took hold across evangelicalism,” she says, “it helped bind together those on the fringes of the movement with those closer to the center, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish the margins from the mainstream.”

Patriarchy drives the game

Du Mez is fully versed in the theological complexity within the American religious community. But her purpose is to reckon with the fact that 81% of self-identifying evangelicals voted for Donald Trump. Few of these people, she points out, read theological tomes, and few are biblically literate. They take their ideological cues from Christian television, the titles prominently displayed in Christian bookstores, the lyrics of contemporary Christian music, the opinions expressed on conservative talk radio and Fox personalities like Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson. And it is this web of ideas, she argues, that defines the parameters of the possible for evangelical pastors.

“Concerns over (biblical) inerrancy gave way to a newly politicized commitment to female submission and to related culture war issues.”

Du Mez uses the struggle for control of the Southern Baptist Convention in the 1980s to illustrate how, for American evangelicals, social issues trump theology every time. “Large numbers of Southern Baptists — even denominational officials — lacked any real theological prowess and were in fact functionally atheological,” she suggests. Which is why, “concerns over (biblical) inerrancy gave way to a newly politicized commitment to female submission and to related culture war issues.”

And it was this commitment, Du Mez argues, that allowed the “New Calvinists” within the SBC to participate in post-denominational networks such as the Gospel Coalition. “Within a generation,” she says, “Southern Baptists began to place their ‘evangelical’ identity over their identity as Southern Baptists. Patriarchy was at the heart of this new sense of themselves.”

In similar fashion, Du Mez suggests, militant masculinity allowed evangelical opinion leaders to paper over theological disagreements. Evangelical authorities were all over the board on the contested subject of eschatology, but it didn’t matter. The authors chronicled in Jesus and John Wayne “patched over a long-standing division within conservative Protestantism” by subordinating theological clarity to a shared desire “to reclaim the culture for Christ by reasserting patriarchal authority and waging battle against encroaching secular humanism, in all its guises.”

Collapse and cover-up

The crumbling foundations of white evangelical militant masculinity were exposed to the world in the years leading up to the election of 2016. One prominent evangelical leader after another stood accused of sexual assault, gross abuse of power or covering up for their evangelical friends. Toward the end of Jesus and John Wayne, Du Mez chronicles the imploding careers of C.J. Mahaney, Mark Driscoll, Darrin Patrick, John MacArthur, James McDonald, Bill Gothard, Ted Haggard, Andy Savage, Doug Phillips, Jack Hyles, Darrell Gilyard and Paige Patterson in excruciating detail.

The rapid implosion of dozens of the men who placed militant masculinity on the evangelical map should have served as a wake-up call. Instead, evangelical icons like Al Mohler and John Piper rushed to the defense of their fallen brothers, making excuses and blaming victims.

“The evangelical cult of masculinity links patriarchal power to masculine aggression and sexual desire,” Du Mez explains, and “men assign themselves the role of protector.” But “immersed in these teachings about sex and power, evangelicals are often unable or unwilling to name abuse, to believe women, to hold perpetrators accountable, and to protect and empower survivors.”

In other words, President Trump is just another exemplar of militant masculinity who gets a mulligan. “Trump might not have been the best Christian,” Du Mez concludes, “but as a Christian nationalist he could more than hold his own.”

Is there hope?

Because militant masculinity is a defining feature of white Christian nationalism, it won’t be renounced anytime soon. Jesus and John Wayne isn’t a book about what more authentic expressions of Christianity might look like; it’s a book about what American evangelicalism has become in the age of Trump and how it got that way.

But by so thoroughly exposing a faux religion rooted in power and privilege, Du Mez poses a provocative question: What would white American evangelicalism look like if we had listened to the civil rights marchers, anti-war protesters, gay rights advocates, and second-wave feminists instead of shutting them out and shutting them down?

Why don’t we find out?