In the land of the free and the home of the I-don’t-have-to-wear-a-mask-if-I-don’t-want-to-even-to-save-lives, we’re less than three months from the presidential election, and it’s getting nastier by the day. On the way to Nov. 3, apparently even God will not be spared.

Bill Leonard

President Trump, speaking recently in Ohio, declared that the Democratic candidate, Joe Biden, is “going to do things that nobody ever would ever think even possible because he’s following the radical left agenda. Take away your guns, destroy your Second Amendment. No religion, no anything. Hurt the Bible. Hurt God. He’s against God. He’s against guns. He’s against energy. Our kind of energy.”

Trump’s probably referencing a certain pop dogma of American exceptionalism that “God, guns and gas make America great.” Yet will Biden, the rosary-toting, transubstantiation-affirming, gun-owning, sometimes-oversharing, cradle Catholic “hurt God” any more than an administration whose policies cage immigrant children, undergird racial inequality and appear functionally inept at reducing deaths in a national pandemic? And what exactly is the source of “our” kind of energy? Gas and oil? Nuclear? Solar? Or Big Macs and sausage biscuits?

Theologizing by and about a candidate’s faith is nothing new in American religio-politics. In the presidential campaign of 1800, Thomas Jefferson’s evangelical critics labeled him a “howling infidel” who professed Christianity but with a dangerous Enlightenment-Deist twist.

When Catholic Al Smith ran on the Democratic ticket in 1928, Methodist bishop James Cannon cast him as a candidate “of the intolerant, bigoted type, characteristic of the Irish Roman Catholic hierarchy of New York City.” Cannon and his supporters were convinced their opposition to Smith would help “to bring in the kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

In the 1960 election, W.A. Criswell, pastor of First Baptist Church, Dallas (that’s in Texas), proclaimed: “The election of (Catholic) John F. Kennedy will lead to the death of a free church in a free state.” Ultra-conservative Baptist millionaire H.L. Hunt, a First Baptist member, funded wide distribution of Criswell’s anti-Kennedy sermon.

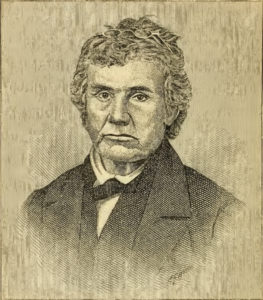

Don’t forget Abraham Lincoln, who in 1846 was an Illinois Whig candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives, his entry point to national office. Lincoln’s Democratic opponent was the Rev. Peter Cartwright, Methodist circuit rider, anti-slavery-anti-liquor advocate.

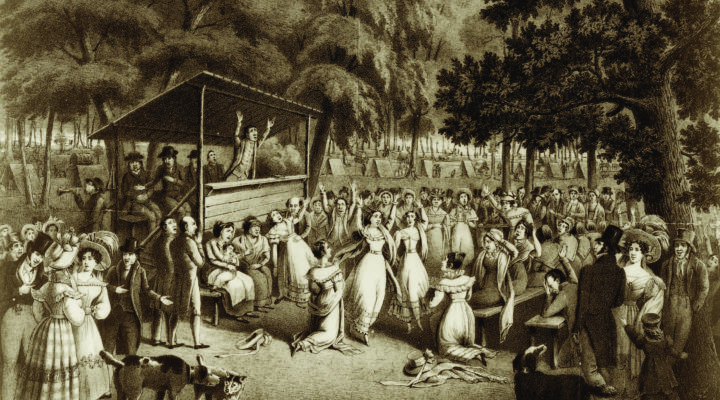

Converted amid the rough-and-tumble frontier camp meetings, Cartwright once bested a tavernkeeper who attacked him, singing All Hail the Power of Jesus Name throughout the fight! Cartwright labeled Lincoln an “infidel,” untouched by the new birth, and without membership in any church.

“Brother Cartwright asks me directly where I am going. I desire to reply with equal directness: I am going to Congress.”

When Lincoln showed up at one of Cartwright’s revival meetings, the evangelist put the reputed unbeliever to the 19th century conversionist test. As the service drew to a close, Cartwright first called sinners to salvation, then demanded: “All who do not wish to go to hell will stand.” The entire congregation rose to their feet, except Honest Abe.

Peter Cartwright

Cartwright then asserted: “I further observe that all of you save one indicated that you did not desire to go to hell. The sole exception is Mr. Lincoln, who did not respond to either invitation. May I inquire of you, Mr. Lincoln, where are you going?”

Lincoln: “I came here as a respectful listener. I did not know that I was to be singled out by Brother Cartwright. I believe in treating religious matters with due solemnity. I admit that the questions propounded by Brother Cartwright are of great importance.”

He continued: “I did not feel called upon to answer as the rest did. Brother Cartwright asks me directly where I am going. I desire to reply with equal directness: I am going to Congress.” (And he did.)

The incident led Lincoln to circulate a “handbill” to voters, explaining: “That I am not a member of any Christian Church, is true; but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular.”

As we all know, Donald Trump’s relationship to Christianity has been a major public issue since the 2016 campaign, especially for the 82% of American evangelicals who voted for him. Rather than defend his faith commitments, most have affirmed his opposition to abortion, appointment of conservative judges and support for Christian schools.

Few evangelical leaders have been more supportive of the 45th president than Jerry Falwell Jr., the erstwhile president of Liberty University who recently was placed on “indefinite leave of absence” by the school’s trustees.

Few evangelical leaders have been more supportive of the 45th president than Jerry Falwell Jr., the erstwhile president of Liberty University who recently was placed on “indefinite leave of absence” by the school’s trustees.

Like many evangelicals, Falwell cautioned against linking Christian commitment too closely to political prowess, noting: “Jesus said, ‘Judge not, lest ye be judged.’ Let’s stop trying to choose the political leaders who we believe are the most godly because, in reality, only God knows people’s hearts. You and I don’t, and we are all sinners.”

He added: “It’s not our job to choose the best Sunday school teacher, like Jimmy Carter was. It’s our job to choose who would defend and protect our nation, who would be the best president.”

Falwell may not be “the best Sunday school teacher” either. His “indefinite leave” from Liberty’s presidency resulted from what the Chronicle of Higher Education described as “posting on social media a photo of himself with his pants partially unzipped and his arm draped around a woman with an exposed midriff.” He also holds a glass of what he called “black water,” a visual challenge to Liberty’s anti-liquor policy.

Falwell Jr.’s 2020 politico-evangelical endorsement of Donald Trump’s second term may carry a bit less weight than in 2016. With friends like that … .

Writing in the Aug. 9 New York Times, reporter Elizabeth Diaz explores that faith-based political connection present among Christians in Sioux Center, Iowa, a community in which Trump’s evangelical support remains strong. After providing interviews with Sioux Center churchgoers documenting Trump’s continued popularity, Diaz concludes: “The Trump era has revealed the complete fusion of evangelical Christianity and conservative politics, even as white evangelical Christianity continues to decline as a share of the national population.” She reminds readers that while there are “signs of fraying,” “mainstream evangelical Christianity has made plain its deepest impulses and exposed where the majority of its believers pledge allegiance.”

“’Our kind of energy,’” infused by Christ’s gospel, requires us to help, not hurt, in addressing the needs, injustices and sins of our time.”

In America 2020, the challenges seem daunting, at times insurmountable: a divisive presidential election, rampant pandemic, Black Lives Matter injustices, joblessness, evictions, voter suppression, school openings and/or closings, increasing gun violence, shuttered church buildings, to name only a few.

Yet beyond shuttered buildings, the body of Christ is not shut down. “Our kind of energy,” infused by Christ’s gospel, requires us to help, not hurt, in addressing the needs, injustices and sins of our time. If that gospel can’t work now, through us, it may not be much help at all.

Politically, perhaps words from that 19th century “handbill” can provide some 21st century courage and hope: “I do not think I could myself, be brought to support a man for office, whom I knew to be an open enemy of, and scoffer at, religion. Leaving the higher matter of eternal consequences, between him and his Maker, I still do not think any man has the right thus to insult the feelings, and injure the morals, of the community in which he may live. July 31, 1846 A. Lincoln.”

Bill Leonard is the founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.