Does hope mean anything anymore? What is the point of hope in this season? I’ve asked myself those questions, along with many, many others in the preceding months and today. I look at the mess we’ve made of the United States and find hope hard to come by.

But then I reread James Cone as I was preparing to lead a book study at my church on his Cross and the Lynching Tree, which compares the crucifixion of Jesus to the lynching of Black Americans in the United States.

Kate Hanch

He critiques Reinhold Niebuhr for failing to grasp the severity of white supremacy in the United States. Cone comments: “Christian realism was not only the source of Niebuhr’s radicalism but also his conservatism … . Rather than challenging racial prejudice, (Niebuhr) believed it must ‘slowly erode.’”

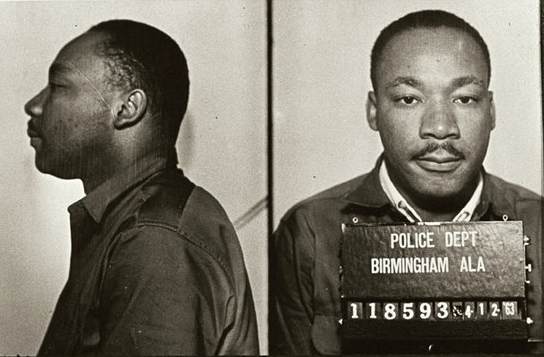

Contrast this to Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. King wonders: “Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world? Perhaps I must turn my faith to the inner spiritual church … as the true ekklesia and the hope of the world.”

This, Cone remarks, marks the difference between Niebuhr and King. Niebuhr “viewed agape love, as realized in Jesus’ cross, as an unrealizable goal in history.” King, on the other hand, knew the standards were high, but nonetheless focused on God doing the impossible — on hoping against the impossible. While the institutional church and Christians on the whole often had failed King, he somehow found hope —even after the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, even after firehoses were turned on Black protesters, even after the lynching of Emmitt Till.

Austin Channing Brown

Cone emphasizes that for King, hope and love “did not erase the pain of suffering and its challenge for faith.” Jesus’ life, death and resurrection — Jesus’ loving hope —compelled King to speak, work and fight, which led him to martyrdom. As Austin Channing Brown remarks: “I get asked about ‘hope’ a lot when talking about race in America. White folks usually mean, ‘Are you optimistic?’ But Black folks connect hope to duty, legacy, the good fight. #Kenosha is why. The freedom movement can’t survive on optimism; there’s too much to mourn.”

Hope is the stubborn ability to believe a better world can be possible. This echoes 2 Timothy 4, where the writer exhorts the audience to proclaim the gospel, in and out of season, even when people “wander away” to versions of Christianity linked to nationalism and white supremacy. The writer, perhaps knowing of his impending death, claims, “I have fought the good fight,” proclaiming truth and righteousness regardless of response — positive, apathetic or antagonistic.

Too often have I found myself agreeing with Niebuhr rather than King. Niebuhr, born and raised a mere 20 miles from where I currently live, may have been concerned about the plight of African Americans but could not, or would not, enter into solidarity with them. Was he afraid he’d lose his job? Or his status as a preeminent ethicist? Or was his heart not open?

“To be a realist can be a luxury when one has found the status quo comfortable.”

Sometimes I think nihilism and moderation — the ability to give up, or the desire to promote gradualism and a “middle ground” — are an indulgence of the privileged and the death of the marginalized. To be a realist can be a luxury when one has found the status quo comfortable.

Realism and nihilism can be easier, I’ve found. I feel helpless to advocate for justice in my own white-flight, largely homogenous community, where the occasional Confederate flag can be found, despite being located in the Midwest. I feel despondent as the pandemic drags on with no end in sight, seeing people I care about suffer its effects, while others deny its seriousness. This election season does not help, either. Why bother with hope?

Then, I remembered Paul’s famous words in 1 Corinthians 13. We see dimly in a mirror now, and still faith, hope and love abide. Paul proclaims the greatest is love.

And what if love informs our hope? What if love informs our faith?

This is how I saw King’s stubbornness in insisting on hope. His love for his Blackness, his love for his community, and his love for the church compelled him to work toward making the world more just. He critiques the church because he loves the church, for “there can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love.” He calls Jesus an “extremist for love.” Because he loves, and he knows God’s love, he hopes against an oppressive government and a segregated church.

Maybe hope looks like love. Probably love looks like expressing disappointment when things aren’t as they should be and working toward what they might be. And perhaps, we might reassess our notions of hope, following the lead of Austin Channing Brown, by ridding ourselves of naïve optimism and rediscovering that obstinate loving hope.

The hope that led Jesus to proclaim relief of the oppressed, good news to the poor, and the captives freed.

The hope that led Jesus to the Cross.

The hope that comes from the Resurrection.

The hope of uprising.

The love that leads to hope. The hope that leads to love.

Kate Hanch serves as associate pastor for youth and families at First St. Charles United Methodist Church in Missouri. She earned a master of divinity degree from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in theology and ethics from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. She is ordained in the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in O’Fallon, Mo., with her husband, Steve.

More by Kate Hanch:

Four radical implications of knowing you are God’s child

Brave peacemaking, not bullying, must be our goal

Amid this pandemic, can we say with Julian of Norwich, ‘All shall be well’?