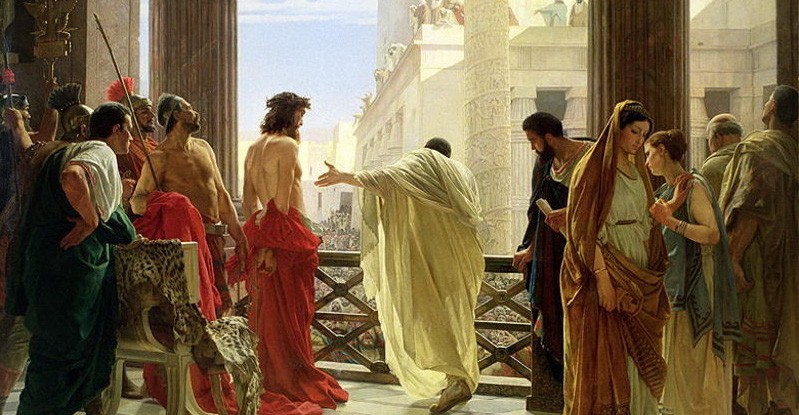

Therefore Pilate said to him, “So You are a king?” Jesus answered, “You say correctly that I am a king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice.” Pilate said to him, “What is truth?” — John 18:37, 38

Pontius Pilate was the Kellyanne Conway of his time.

Questioning truth is an old pastime, and the Roman governor likely was familiar with Greek philosophers who made a living at it. But it took some guts to do it in a high-pressure political situation — and in response to the Son of God, no less. On the other hand, as one of Donald Trump’s legion of double talkers, media huckster Conway has mere reporters and TV viewers to befuddle when she whips out her “alternative facts.”

Erich Bridges

Her strategy, however, is essentially the same as Pilate’s: Cloud the issue. Muddy the waters. Cast doubt on the facts. And thereby drown the truth in distortion.

Shakespeare was well-acquainted with the distortion tactic, a close relative of state censorship in Elizabethan England (you could lose your head for uttering uncomfortable truths in those days). “Tir’d with all these, for restful death I cry,” he lamented in Sonnet 66:

… art made tongue-tied by authority,

And folly (doctor-like) controlling skill,

And simple truth miscall’d simplicity

Things have gone downhill since then. Only simpletons still believe there is one truth, right? Or that truth even exists. Pilate would be quite comfortable in our time, when everything is up for debate.

Truth — whether in religious, moral, political or plain old factual form — has been under attack for generations. Too many preachers have been exposed. Too many politicians have lied. Too many old heroes have been tarnished by new revelations. Too many institutions are corrupt. Why believe the “experts”?

I’ve been pondering these questions since completing post-doctoral work at Oxford University, where I debated epistemology with some of the world’s great philosophers. Did you believe that last sentence? Gotcha. I graduated from a commuter college in Atlanta with a humble bachelor of arts degree. But why not embellish the old resume if no one is going to verify it?

Settling for “truthiness” is easier than pursuing hard truth. If it feels right or the culture pushes it, go with it. The one unforgivable sin these days is to be judgmental — unless you’re attacking those who resist whatever groupthink dominates at the moment. And herd mentality rules not only among the unwashed masses: Academia enforces political “truthiness” among scholars and intellectuals with vicious efficiency. Fact-check the commissars and you will be cancelled in a nanosecond.

“It’s a wonder we still agree on the few truths most of us generally accept.”

It’s a wonder we still agree on the few truths most of us generally accept. But that list of accepted truths shrinks daily. There is no fatherly Walter Cronkite to voice them, no universally respected authorities to curate them. We are fragmented by social alienation and digital technology into countless pieces, possibly beyond repair.

If things weren’t confused enough, yet more tidal waves of distortion have washed into this swamp of confusion: Fake news. Conspiracy theories. Q-Anon and other faceless purveyors of dark fantasies that millions of gullible people actually believe.

Much of it originates abroad, in Russian or Chinese troll farms digitally sending lies our way day and night. But there’s plenty of homegrown fakery; just check President Trump’s Twitter feed, faithfully followed by his true believers. He makes up, or retweets, countless whoppers each week, while continuing to call legitimate news organizations “enemies of the people.” Print newspapers, meanwhile, are dying daily for lack of readers and advertisers.

Amid such an atmosphere of untruth — with an ongoing pandemic on top of it — we struggle to keep hold of reality. Older people seem to be especially susceptible to fake news, perhaps because of lack of “digital literacy” or the cognitive decline that also makes them vulnerable to telephone scammers and marketing hoaxes.

But young people are just as susceptible, maybe more so. A recent national survey found that 18- to 25-year-olds had an 18% probability of believing false claims about the coronavirus — twice as high as people over age 65.

“Rebuilding a national culture of truth-telling and mutual acceptance of basic facts will be a long, challenging project.”

What can be done? Rebuilding a national culture of truth-telling and mutual acceptance of basic facts will be a long, challenging project. But each of us can be a part of it. It is a moral and spiritual imperative. Satan is the father of lies. Jesus says the truth will make us free.

Refuse to accept dubious claims of fact without checking them out. Challenge people who throw them around — even if it’s your Uncle Fred or one of your fellow church members. You might lose some friends, but it’s ultimately a price worth paying.

Read reputable (and multiple) newspapers and news sites. Yes, they’re all biased to one degree or another and always have been. That’s why you need to read more than one. Make sure they represent different social and political perspectives. Don’t become the willing captive of an echo chamber that endlessly confirms your own opinions.

Here are some free fact-checking resources to help you on the way:

- https://www.factcheck.org/

- https://www.politifact.com/

- https://www.snopes.com/

- https://www.poynter.org/media-news/fact-checking/

- https://www.poynter.org/mediawise-for-seniors/

- https://www.coursera.org/learn/news-literacy (free online course)

Erich Bridges, a Baptist journalist for more than 40 years, retired in 2016 as global correspondent for the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Mission Board. He lives in Richmond, Va.

Related articles:

Where do you go for news you can trust?

Telling the truth or creating our own realities? (And the wisdom to know the difference)