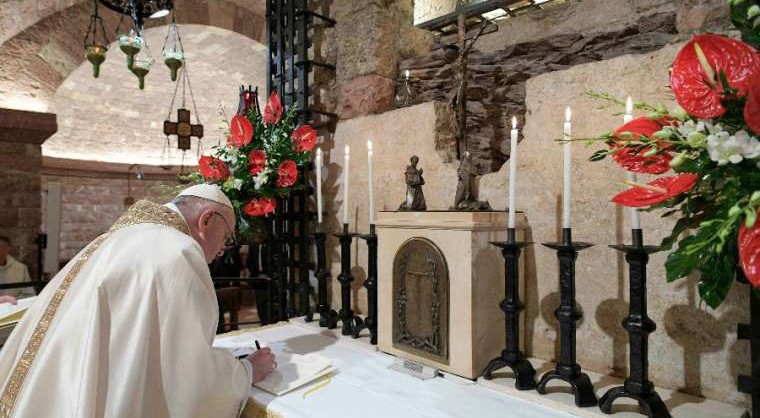

On Oct. 4, Pope Francis published his third papal encyclical, Fratelli Tutti. Like all titles, Fratelli Tutti is revealing. Not only does it allude to the writings of the Pope’s namesake, St. Francis of Assisi, it also previews the themes of the document. The Italian translates to “all brothers,” and Pope Francis spends 287 paragraphs pleading with “all people of goodwill” to build a better world, one marked by the principles of human dignity, fraternity and solidarity.

This is a document marked by the highest ideals of Christian theology, but also by an eminent practicality. Francis notes frequently that his vision will require hard work, especially as his goals include eliminating the death penalty, permanently avoiding war, exorcising the demon of racism, and raising serious questions about the nature of private property. This encyclical is not for the faint of heart.

What is an encyclical?

Like Francis’ previous encyclical Laudato Si’, Fratelli Tutti is addressed to “people of goodwill,” in hopes that it will be read, discussed and implemented by more than just the world’s Catholics. It is, after all, a vision for worldwide fraternity and solidarity.

Pope Francis

At the same time, also like Laudato Si’, Fratelli Tutti should not be divorced from its context as a papal encyclical. It is a document awash in the theology and rhetoric of the Roman Catholic Church, and it has particular implications for Catholics the world over.

This is because an encyclical is one of the highest manifestations of Pope Francis’ teaching authority. These documents are generally not considered to be infallible, but they are considered authoritative. Broadly speaking, encyclicals instruct the faithful on how to apply Catholic theology and spirituality in the present moment, often in relation to a specific issue.

For example, Laudato Si’ offered guidance on how Catholics should respond to climate change. But previous encyclicals have dealt with a range of theological issues. One of the first encyclicals of the modern era was Rerum Novarum, published in 1891 by Pope Leo XIII, which discussed capital, labor and the rights of workers. Another important encyclical is Paul VI’s Humae Vitae (1968), which reaffirmed traditional Catholic sexual ethics and rejected the possibility of artificial contraception.

Like other encyclicals, the pope’s latest is a document all Catholics should take seriously. Even though it may offer new and jarring interpretations, it is firmly rooted in a body of thought often referred to as “Catholic Social Teaching.” While there can be sharp disagreement over how to apply them, the principles of solidarity, subsidiarity, human dignity and concern for the poor are all deeply engrained in Catholic Social Teaching, and Fratelli Tutti should be regarded as an extension and elaboration upon the application of those basic moral principles in this present moment of global crisis.

What does it say?

Fratelli Tutti also differs from other modern encyclicals in that it is not truly an original document. Instead, the encyclical gathers and organizes Francis’ comments on fraternity and solidarity from the various speeches and letters of his papacy to date. Roughly 60% of the document’s 288 citations are from sources delivered by Francis in other contexts. Thus its themes will not be surprising to anyone who has followed Francis’ pontificate, although the cumulative impact of the collected material is certainly striking.

The first full chapter, “Dark Clouds Over a Closed World,” excoriates the social and political problems of the present moment.

Although Pope Francis notes multiple times throughout the letter that he could be accused of naivete, he is not shy about grounding Fratelli Tutti in concrete reality. The first full chapter, “Dark Clouds Over a Closed World,” excoriates the social and political problems of the present moment.

Francis articulates a litany of woes: the resurgence of demonic ideologies like racism and nationalism, unfettered capitalism, globalism without respect for culture, devastating wars, social isolation, and the failure of the global community to respond to the coronavirus pandemic. Worst of all is the deadly cynicism that plagues us, making “a plan that would set great goals for the development of our entire human family nowadays sound like madness.”

Francis’ solutions may be idealistic, but his diagnosis is firmly grounded in the lived reality of millions.

The theological heart of the encyclical is found in chapter two, where Francis spends time reflecting on the parable of Jesus’ that we often call the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37). It is a reflection soaked in the Ignatian spirituality of Francis’ Jesuit background, and it asks readers to place themselves within the text before calling them to the moment of decision.

“Will we bend down to touch and heal the wounds of others?” Francis asks. Or “will the wounded man end up being the justification for our irreconcilable differences?” It is only in truly encountering the suffering of our fellow humans that we give them the dignity of our common life, and it is in experiencing that same suffering that we have the potential to be changed.

This encounter with the other is the basis for human society and sociality, Francis argues. “Human beings are made so that they cannot live, develop, and find fulfillment except ‘in the sincere gift of self to others,’” therefore society must be ordered in such a way that facilitates that sincere gift.

The encyclical calls for building an open world, but it is not a naïve call. Francis is well aware that these things are “the result of the conscious and careful cultivation of fraternity.” Elsewhere he describes those who build this open society as “artisan(s) of peace,” and it is clear that Francis intends for his readers to roll up their sleeves and get to work.

Because the goods of the earth belong to everyone, states must be willing to accept those who migrate to meet material needs.

Francis has specific tasks in mind. We must reorient our relationship to private property, remembering that the primary goal of created goods is “common use.” And because the goods of the earth belong to everyone, states must be willing to accept those who migrate to meet material needs. Likewise, awareness of our common life should lead to care for the poor and for the earth. Francis also calls for an integrated global political and economic structure so that global afflictions like human trafficking can be eradicated.

All of this supported by a new kind of politics that respects culture, honors diversity and is truly oriented toward the common good. Politics is, after all, another form of love, one Francis describes as “charity as its most vast.”

Already, this is a monumental task, but Francis is not finished. By far the most challenging and controversial goals of the encyclical are laid out in chapter seven, “Paths of Renewed Encounter.”

Drawing on centuries of Catholic moral theology, Francis clarifies and strengthens the Church’s positions on war and the death penalty.

War, Francis argues, is now so destructive to humans and the planet alike that it can no longer be considered just in any form. “Never again war!” he cries.

Likewise, the death penalty, on some level simply “another way to eliminate others,” must itself be eliminated. Not only is its practice rife with abuse and error, but it eliminates the possibility of repentance and destroys someone who continues to bear the image of God and the dignity that confers. To build a loving society, the death penalty must be eliminated.

To build a loving society, the death penalty must be eliminated.

Francis concludes with prayer, but not before reiterating the hard work required for this task. He calls for “artisan(s) of peace,” reminding us that politics rightly conceived is both art and labor. For the sake of our neighbors, Francis pleads, we must take up the task.

What will Fratelli Tutti mean for the world?

It is hard to say what exactly this encyclical might mean for the world, and especially for its 1.2 billion Catholics. By comparison, Francis’ other “social encyclical” Laudato Si’ was published more than five years ago, and climate change remains the greatest existential threat humans face.

While Laudato Si’ certainly has motivated individuals and even institutions and organizations to take concrete steps to combat climate change, groups like Extinction Rebellion continue to warn that it may already be too late to stop the effects of climate change.

The stakes are equally high for Francis’ vision of society. If his diagnosis of the present moment is correct, humanity occupies the most conflictual, divided and unjust period in human history.

Incremental change is not going to be enough for those who suffer from poverty, war, human trafficking, organized crime, COVID-19, alienation, isolation and all the other ills Francis discusses.

In the end, his reflection on the Good Samaritan looms large. Will this generation walk past human suffering and choose not to pay attention? Or will we see both human dignity and the face of Jesus in the one who suffers? Will we rationalize our refusal to help? Or will we bind up wounds and be healed ourselves? Only time will tell.

Aaron Coyle-Carr is a graduate of Candler School of Theology at Emory University. He’s currently a stay-at-home dad, Bible study teacher and researcher based in Dallas. He is married to Leanna Coyle-Carr, who also is a Baptist pastor.

This article was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.