When they flipped his body over, the bright canary yellow blanket fell on the grass. His hoodie was damp because he’d been laying there a while and it had been raining that night. He was wearing jeans and fresh Fusion Force 20s. The red, black and white ones with the red strap and the patterned flap.

I recognized the Jordans because my brother has a pair. His fade was cut the same and his skin was a darkened caramel color too. That could have been my brother under that sheet. His 7-Eleven lighter was strewn on the lawn along with the Skittles he’d bought his own little brother, and they found the AriZona iced tea a little bit later.

Tamice Spencer

I didn’t sleep that night. I kept thinking about the shoes.

That Sunday when I went to church, we sang happy songs about God’s goodness and glorious reign, and no one talked about Trayvon, not even the pastor. We sang songs about joy and gladness the week the 911 tapes came out, and we prayed for revival during the rallies in Sanford.

In November of the same year Trayvon died, Jordan Davis was shot to death because a white man thought his music too loud, and Rekia Boyd was shot in the head while leaving a pool party because the officer who approached her group thought her cell phone was a gun. At church they talked about how sad it was that the guy from Glee died. I remember because it was the same day the jury acquitted Trayvon’s killer. They didn’t know anything about that. They didn’t even know his name.

I began to feel a deep and nauseous sadness that became more and more unbearable. I told my friends about this, but they didn’t understand why I would be so upset about some thug in Florida being in the wrong place at the wrong time or why I was concerned about how many white people were on the jury of that other trial I’d been telling them about — the one where the boy stole the Snickers and died.

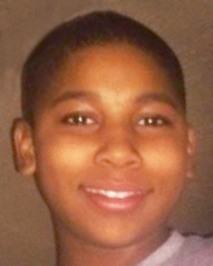

Trayvon Martin

His name was Trayvon, and he didn’t steal, I told them. I didn’t tell them about my brother, and I didn’t tell them about his shoes. They didn’t deserve to know.

Renisha McBride

A year later in the middle of the night, Renisha McBride was shot in the face with a 12-gauge pistol-grip Mossberg shotgun. She was shot through a screen door on the porch of one of her neighbors because she was knocking too loudly. A year later in New York, Eric Garner was choked to death in broad daylight for selling Newport Kings, the kind Rigby, my auntie, used to smoke. She called them “loosies.” Eric told the officer he could not breathe, but it didn’t matter.

In Ohio one month later, John Crawford was shot inside a Walmart for picking up a gun they sold in the store while his girlfriend gathered ingredients to make s’mores. Michael Brown was shot six times and left lying face down in Ferguson, Mo., in August in the middle of the road. The officer let his body fry on the asphalt of his neighborhood for four hours in front of his mother’s house. Two days after that, Ezell Ford was shot in the back at close range for walking in the street. So was Laquan McDonald, only he was shot 16 times in 13 seconds.

Tamir Rice

The next month, a 12-year-old boy was shot in the torso for playing with a toy gun in the park; he died the next day. His name was Tamir Rice. In April of the same year, Freddie Gray’s spinal cord was snapped in half while he was being transported by police for possessing what they referred to as an illegal switchblade; they didn’t buckle him in when they drove him away.

In November, Jamar Clark was shot in the head while handcuffed and Akai Gurley was shot to death while walking down the stairs. Walter Scott was shot dead by an officer who lied in his report. And just across the town border only two months later, nine Black men and women were massacred in their own church during Bible study.

Philando Castile

Alton Sterling was selling CDs out of his trunk at a corner store in Baton Rouge when he was pinned to the ground and shot five times, in the chest, at close range. And the very next day, the entire world watched live as Philando Castile bled to death in front of his 4-year-old daughter and his girlfriend. He was shot seven times while sitting in the passenger seat. He was wearing his seatbelt.

But still the pastor didn’t talk about it.

“Numb” is not the right word because it was sharper than that. “Angry” won’t suffice either because it was deeper. It was as if the world was spinning, and I could not find my balance. With every hashtag, the crack in the toxic foundations of my faith grew wider. Where do you run when all you’ve been given is White Jesus to turn to? I could not breathe. I could not sing another damn song about joy. I didn’t know it then, but I was fellowshipping with the 81% and there was leaven in the bread.

How could they be so oblivious to the issue at hand? How could they not see it? Why did they argue with me so much about it? Why did I have to calm down?

They were convinced all those who had been killed had done something wrong, something to deserve being gunned down like beasts with no family, no future and no dignity. Why were all the pictures of the slain so dark and thuggish? Why were all the murderers shown in uniforms and family photos? The anguish was unbearable. It was the culmination of so many things I’d ignored for so many years.

How many Black bodies have to drop before they cared? Didn’t Jesus care? Why didn’t they know any of their names? And why did all the GoFundMe money go toward George’s bail instead of Trayvon’s burial? Deep inside I knew something was happening to me, and I knew it was the beginning of the end. Of what? I didn’t know, I hoped it wasn’t my faith, but I honestly didn’t care.

“I couldn’t see Jesus past the pile of dead Black bodies anyway. I spent the next two years in mourning.”

I couldn’t see Jesus past the pile of dead Black bodies anyway. I spent the next two years in mourning.

It felt like there was trauma in my bones. Like I was carrying the pain and the weight of the entire struggle for freedom and dignity and I couldn’t decide if I wanted to be free. The pain at once made me feel connected to a narrative I’d only just begun to know and removed from a community I’d come to know too well.

I chose the new narrative because in an odd way, being united with my ancestors was better than the enmeshment of the 81%. This pain gave me a sort of strength and it began to lift me. Right as I began to pick myself up, Donald J. Trump was coming down an escalator to announce his run for the presidency.

And I began seeing red.

Suddenly all those who’d encouraged me to be careful not to lose my integrity and to try and be more respectful on social media platforms didn’t apply that ethic to the leaked audio of their pundit’s boastful remarks on sexually assaulting women; “it’s locker room talk,” they said. The colleagues who’d gone on and on about facts when it came to police shootings, dismissed facts when it came to unfavorable media reports; “it’s fake news” they said. The leaders who told me anger was unbecoming railed against the young teens who were peacefully protesting the installation of the Dakota Access Pipeline and the availability of military-grade assault weapons to civilians. With every news story dripping with corruption and misogyny, bigotry and greed, xenophobia and deceit — the 81% has continued to stand unrelentingly still. I knew it was only the beginning.

“The uninformed opinions of the 81% cannot and do not weigh more than a lifeless Black body.”

But I wasn’t ready.

I raged and I cried.

I argued and I lamented.

I mourned and I groaned.

The uninformed opinions of the 81% cannot and do not weigh more than a lifeless Black body. So, two years and one Charlottesville later, I let it go. For there is nothing hidden that will not be exposed, and wisdom is justified by her children.

The Trump administration has been a gauntlet for the faith of this weary Black soul, but I suppose the hysteria taught me to take my place and stay there.

I am approaching this election less naive and more faithful. As I watch the leaders fumble, the idols topple and all the statues come down, I am approaching the election with hope. A hope rested not upon the outcome of the election, but in the inevitability of the justice of God and the vindication of the righteous.

I’ve realized that standing our ground is all we can really do. I find a terrible irony that I am right back where I started, seeing as how “stand your ground” is the phrase that sparked the journey toward this beautiful and arduous amelioration of faith and orthodoxy.

In a way I am thankful. The experience of seeing the contrasting realities, the deceit and the idolatry that the 2016 election exposed breathed life when I’d thought my bones could no longer live. The breath of God transformed my trauma into a tempest, the tempest pulled up every root, and the journey planted them down deep into the soil of an ardent hope.

When people ask me about my story, I tell them about Trayvon. I like saying his name; I owe it to him. And if I sense that they are hearing me, I say all their names.

There are people who have more tragic stories to tell than me, but mine is worth telling. It is a story about how the evangelicalism that served as the foundation of my faith was almost the cause of its demise. It is a story about what it feels like to be hanging on to belief by a tiny thread and the fear of disclosing it to anyone. It’s a story about loss and failure and disillusionment; a broken heart and a broken will.

It’s also a story about survival, and it began with Trayvon Martin and his shoes.

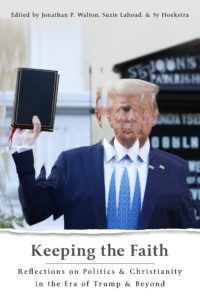

This opinion piece is excerpted from a new book, Keeping the Faith: Reflections on Politics & Christianity in the Era of Trump and Beyond, which brings together 36 Christian leaders from across the country who challenge the notion that Donald Trump is the de facto Christian choice in the 2020 presidential election. Contributors include leaders and emerging voices from across the political spectrum, including Alexia Salvatierra, Randall Balmer, Andy Crouch, Brandi Miller, David French, Randy Woodley, Greg Coles, Tamice Spencer and Miluska E. Aquije.

This opinion piece is excerpted from a new book, Keeping the Faith: Reflections on Politics & Christianity in the Era of Trump and Beyond, which brings together 36 Christian leaders from across the country who challenge the notion that Donald Trump is the de facto Christian choice in the 2020 presidential election. Contributors include leaders and emerging voices from across the political spectrum, including Alexia Salvatierra, Randall Balmer, Andy Crouch, Brandi Miller, David French, Randy Woodley, Greg Coles, Tamice Spencer and Miluska E. Aquije.

Tamice Namae Spencer has 15 years of experience in full-time young adult ministry. In 2018, she established the faith-based nonprofit Sub:Culture Inc. to provide Black students with the resources and guidance needed to successfully incorporate their religious beliefs into their academic, professional and personal lives, and to become pillars within their respective communities.