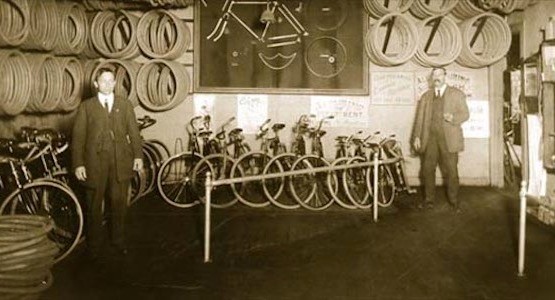

In the movie “Seabiscuit,” an early sequence shows how the fabled racehorse’s owner, Charles Howard, transformed his bicycle-repair business into the San Francisco Bay Area’s most successful automobile dealership in the early age of motoring. Howard met the challenge of what business school professors call a “tectonic event” — a happening that totally shatters a company’s reason for being, resulting in either death or transformation.

The year 2020 has been such an event for the entire world, but it has been particularly hard for The United Methodist Church. Born at the same time as the United States of America — in fact founded because of the American Revolution — today’s United Methodist Church has fallen prey to forces similar to those confronting American democracy. In short, its system is broken, and its leadership now is trying figuratively to change a flat tire on a car that’s still moving.

“Today’s United Methodist Church has fallen prey to forces similar to those confronting American democracy.”

The role of bishops

The idea of bishops as the church’s executives goes all the way back to biblical times. The Apostle Paul instructs his protégé Timothy in the qualifications of a bishop in 1 Timothy 3.1-6:

“The saying is sure: whoever aspires to the office of bishop desires a noble task. Now a bishop must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money. … “

Today some branches of Christianity have retained the concept of bishops as those who supervise other clergy. During the life of The United Methodist Church, which was formed in 1968 through the merger of two denominations, bishops have become supervisors of more than clergy. United Methodist bishops are known as “general superintendents” of the church, with multiple responsibilities for “spiritual and temporal” church life. Those obligations make for real-life burdens that few people would care to assume.

Institutionally, United Methodism shares a three-part governance structure mirroring that of the United States, with legislative, executive and judicial branches. Each branch today shows major ruptures in its operations, but its executive arm — the Council of Bishops — currently exhibits the most precarious state.

Each bishop is assigned to an “episcopal area” — a geographic region consisting of 100,000 or more church members — and is ultimately responsible for the operation and upkeep not only of clergy but also of all local congregations and affiliated ministries within that region. In effect, he or she (United Methodism is one of the few denominations that elects and consecrates female bishops) serves as the chief executive officer of what amounts to a mid-size division of a multi-million-dollar international religious corporation.

A bureaucracy that no longer works

These days the worldwide corporation of United Methodism faces the kind of threat that overwhelmed Charles Howard’s bicycle-repair shop. The church’s way of fulfilling its mission — to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world — through a far-flung network of bureaucratic units no longer works. As with many corporations, the CEOs, the bishops, get most of the flak when things go wrong. Sometimes the bishops deserve criticism; in the current situation, however, they’re more affected by circumstances than by their own performances.

United Methodism has been plagued by its bureaucratic structure for decades, symbolized most clearly by the “user’s manual” that bishops are supposed to execute: the 900-plus-page Book of Discipline. The cumbersome, complex and contradictory collection of church laws and policies wasn’t made for an era in which a global pandemic utterly upends life as we know it. Nonetheless, the bishops are stuck with the Discipline, which is created by the church’s legislative branch, and its requirements are getting in the way of the bishops doing what 2020’s tectonic events demand.

Cynthia Fiero Harvey, current president of the UMC Council of Bishops. (Photo: UMC News Service)

The Council of Bishops spent four days in early November consulting with one another and outside experts about how to lead in this “liminal time,” as Bishop Cynthia Fierro Harvey, the council president, termed it. Primary among its concerns was the sharp decline of the Episcopal Fund, the church-wide account fed by local church contributions that pays the salaries, benefits and operational costs for 66 active bishops in the United States, Europe, Africa and the Philippines.

Diminishing financial resources

In 2019 the United Methodist Council on Finance and Administration warned the bishops that their money would be gone within five years. Now with the depleted economy caused by the coronavirus pandemic cutting into offerings across United Methodism, the Episcopal Fund has declined even more precipitously. As Heather Hahn of UM News reported Nov. 6, the United Methodist General Council on Finance and Administration Fund estimates that the Episcopal Fund will receive about $17.4 million this year, roughly 75% of the requested “fair share” contributions known as apportionments.

As a result, the Council of Bishops has recommended that no new bishops be elected during the current four-year cycle, and that the addition of five bishops in Africa, where the denomination is growing, also be postponed. Such a proposal is unheard of in United Methodist history, but the choice is out of the bishops’ hands. Again, mirroring how Congress votes on the president’s budget, it’s the General Conference that sets the bishops’ budget and therefore the number of bishops who lead the church.

“The money problem brings only one facet of the overall challenge facing the bishops.”

However, the money problem brings only one facet of the overall challenge facing the bishops, namely the likelihood that within the next few years, The United Methodist Church will split into two, three or more denominations. The prospect seems so inevitable that even the denomination’s ministry coordinating agency, the Connectional Table, has initiated a project, “Emerging Methodism,” that seeks “to foster … reflection … through an open-ended conversation about what is emerging in Methodism,” according to its page on the official ResourceUMC.org website.

Unfortunately, there’s no time for the kind of leisurely deliberations that United Methodists love. The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the political and theological motivations that have pushed United Methodism to the brink of breaking up. Added to those ideological disputes, centralized governance has become intractable as local congregations scramble for ways to continue their ministries despite public health restrictions aimed at curtailing the deadly virus. Unable to gather together in many cases, church members are falling away, fearful of infection by the coronavirus plague or overcome by economic privation caused by the pandemic. Sustaining the church has become more than many members can handle.

Like the rest of the world, The United Methodist Church’s fate is being determined by forces beyond its bishops’ control. Constrained by an outdated organization, few bishops are experienced in how to lead outside a system that’s falling apart. Yet that’s exactly what the bishops are being called to do, and United Methodists are waiting to see how their leaders respond.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

This story was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.

Related articles:

African bishops demand independence in deciding United Methodist Church’s future

Is the United Methodist separation still on?

Death of a bishop, birth of a new denomination intertwined for UMC

Another United Methodist plan demands patience more than specifics