When I tell my friends and family that I participate in spiritual direction, I am most often met with a blank look, followed by a “What?” As with many things of faith, it can sometimes be hard to find adequate words to share with others.

In the fall 2012, I sat in the chapel of Truett Seminary at Baylor University in my first covenant group orientation. As a lifelong churchgoer, even attending a Baptist high school with weekly chapel and daily Bible classes, I was a little frustrated that I was just now connecting with the diversity of historic practices that help people commune with God. I was anxious to begin exploring some of them with my newly assigned small group of seminary peers, my covenant group.

Liz Andrasi Deere

Over the next two years I learned to practice lectio divina, times of silence, discernment and prayer. Truett professor Angela Reed led that orientation and began guiding me down a path toward greater understanding of what it means to be in deeper relationship with God and with other believers.

During a one-on-one spiritual direction session, Reed invited me into imaginative prayer. She asked me to imagine a peaceful scene. I sat with my eyes closed, breathing deeply as I imagined sitting on the floor of a forest with my back leaning on a tree. She began to describe Jesus walking toward me and sitting down next to me. She guided me as I stayed focused on this moment for a while. Then, after the prayer, I shared what the experience had been like and how I had experienced the presence of God.

It was in these moments that I began to consider that perhaps Jesus really could be my friend. I had always been told he could but had never really understood how.

Spiritual direction remains an important, regular practice in my life. After I moved to Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, I began meeting for weekly spiritual direction with Adriana Nicholson.

Most people meet one-on-one for direction about once a month.

Most people meet one-on-one for direction about once a month. Spiritual direction can be flexible, however, and what I needed was someone who would sit with me often and let me be honest about my wrestling with God. I was a newlywed living away from Texas and all my friends and family for the first time. Through our time in direction, God was present as I continued to unpack my images of God and my understanding of myself and my identity in this new season of life.

As we began each session Adriana lit a candle as a reminder that it was not just the two of us present, but the Holy Spirit as well. An image of the holy Trinity sat on the table next to us and I often found myself gazing at God’s communion.

Recovering the roots of Baptist spirituality

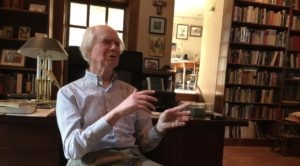

Glenn Hinson is a Baptist church historian and biblical scholar whose work embraces a posture of ecumenism. His ministry of writing and teaching spans six decades, during which he has educated and invited countless Baptists to engage with broader church history and spiritual practices. The thrust of Hinson’s book Baptist Spirituality: A Call for Renewed Attentiveness to God is that Baptists should return to the contemplative tradition which marked our beginnings.

Baptists have deep roots in spiritual practices from Puritan forebears; the primary distinction of early Baptists from Puritans was believer’s baptism by immersion, which began to be practiced around 1640. As Hinson states: “Puritanism was spirituality. Puritans were to Protestantism what contemplatives and ascetics were to the medieval church … . Where monks sought sainthood in monasteries, Puritans sought it everywhere — in homes, schools, town halls and shops as well as churches … . Like the monks, Puritans were zealous of heart religion manifested in transformation of life and manners.” These were the practices forming early Baptists.

Baptists have deep roots in spiritual practices from Puritan forebears; the primary distinction of early Baptists from Puritans was believer’s baptism by immersion, which began to be practiced around 1640. As Hinson states: “Puritanism was spirituality. Puritans were to Protestantism what contemplatives and ascetics were to the medieval church … . Where monks sought sainthood in monasteries, Puritans sought it everywhere — in homes, schools, town halls and shops as well as churches … . Like the monks, Puritans were zealous of heart religion manifested in transformation of life and manners.” These were the practices forming early Baptists.

There is a historical reason why Baptists drifted from these roots, Hinson says.

In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the images, icons and liturgies of the Catholic church were left behind in favor of the written and spoken word. Yet early Baptists embraced confessing their sins to one another and participated in exercises that looked remarkably like Saint Ignatius of Loyola’s daily examen. But over time, the moment of conversion began to be held up as the marker of greatest importance in the journey of faith, and the numbers of those who had been “saved” became a quantitative marker of success of the church or missionary enterprises. Additionally, as Hinson says, “The business model has imposed itself on Baptists in America, and Baptists have bought into the success motif of the corporate world.”

David Stamile is a graduate of Truett Seminary, where he obtained the spiritual director certificate. During his training as a spiritual director he taught Dying and Death Education for the department of public health at Baylor University. He also served as a hospice chaplain. (Photo by Emmitt Drumgoole)

A return to the Baptist heritage of spirituality offers something rich. By embracing spiritual direction, and the practices it incorporates, people can once again make slow, steady, movements toward God. They can find space to be deeply known, where sins can be realized and confessed, and they can be encouraged to notice God in all aspects of life.

But to participate fully takes ample time and commitment. There is no successful completion of a program, or monetary or soul acquisition to report. Instead, the outward signs of the inward realities people experience are things like love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.

What I learned in seminary

At Truett Seminary, Professor Reed serves as associate professor of practical theology, director of spiritual formation and director of the Spiritual Director Training Program. Her passion for spiritual formation, particularly spiritual direction, began when she was ministering to a congregation in the late 1990s.

Regarding that time, she said, “Somehow I struggled to get from that point of kind of casual conversations about everyday life to matters of the soul. I didn’t know how to have conversations at the level of soul with people … . When I first received spiritual direction for myself, I think I discovered there what I thought ministry was supposed to be about. How I could learn to ask what I’ve come to call ‘God questions’ and have that kind of interaction with people.”

Reed co-authored a book, Spiritual Companioning: A Guide to Theology and Practice, and she explained they chose the term “spiritual companioning” rather than “spiritual direction,” in part to help dispel the confusion that spiritual directors tell directees what to do. This is not that sort of direction.

Rather, the spiritual director walks alongside as a companion and directs attention to God. They provide a space to explore the heart of what it means to be a human in relationship with God and with others, in all aspects of life. As Paul Jones says in his book, The Art of Spiritual Direction, “The real director is the Holy Spirit, for simply to live is to be pursued by the divine presence.”

Angela Reed (photo by Emmitt Drumgoole)

The Spiritual Direction Training Program at Truett is one of many such programs around the country. Baptists join the tradition of training alongside other Protestants, as well as Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Eastern philosophers, to name a few of the most prominent streams.

Spiritual direction can be practiced one-on-one — in person or remotely via video chat, but it also may be adapted for small groups and for congregational direction. At its core, spiritual direction is a posture of holy listening and noticing. It is an adaptable practice that can inform how one relates to God through childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, middle-life and senior adulthood.

Programs like the one at Truett train directors to be spiritual companions who are able to listen non-judgmentally, to ask questions as they are prompted by the Holy Spirit, and to lead others in spiritual disciplines that open them up to experiencing and noticing the presence of God.

In recent years, spiritual direction and spiritual practices have become more familiar to Baptists as more train to be directors and more churches hire directors onto their staffs, offer spaces for group spiritual companioning, and refer congregants to local directors for one-on-one direction.

Preparing to companion

The journey to become a certified director is full of study, practice and reflection. The work requires an atmosphere of comfort and vulnerability.

Rory Jones is a graduate of Truett Seminary, where he obtained the spiritual director certificate. He joined the program because he was the leader of the young adult Sunday School class at Calvary Baptist Church in Waco and was looking for a way to help young adults through life and career transitions. (Photo by Emmitt Drumgoole)

Jesus taught in parables as a way to help those who listened to him grasp a taste or an image of mysterious spiritual truths. In many ways, what happens during a spiritual direction session, whether one-on-one or in a group, can be hard to put into words. Two students in the first cohort of Truett’s Spiritual Direction Training Program, David Stamile and Rory Jones, turned to images to help explain how they have experienced receiving and offering spiritual direction.

Stamile described spiritual direction as a way to break free from prisons within oneself.

“I really can point to a lot of ways that I was sort of locked in various prisons — feeling spiritually inferior, having a view of God that was not really loving,” he said. “I think of those as sort of prisons, and I can point to and remember moments where people have come alongside me and they had the keys.”

Training to be a spiritual director provided him with more keys to offer people as they seek freedom from their own prisons, he added. While training, he taught a class for Baylor undergraduate students and incorporated spiritual direction into the curriculum. In the students’ reflections of their experiences, many expressed that people do not usually give them the time to take a break and give them space to talk about their lives without giving advice. Receiving spiritual direction was a positive experience for many of them, he reported.

Jones thinks of spiritual direction as participation in an act of sowing seeds. There is hope involved as directors and directees tend to the seeds God is sowing and watch the fruit unfold over time.

He reflects on his first time receiving spiritual direction, “I walked away from the hour and said, ‘Wow, direction is really for people who want to take their spiritual life seriously; want to be intentional about the growth they’re seeking; want to dig more deeply in the Christian tradition.’”

He emphasized the Baptist distinctive of soul competency as being a vital reason to engage disciplines like spiritual direction: “You’re discovering what your own pathway is to God, the way you relate best to God, the way you hear God’s voice most clearly, the ways you become aware of God’s will for your life in prayer.”

In today’s culture, genuine connection with another person can be rare. Social media mediates our contact with other people, daily life quickly fills with movement from task to task, and it is countercultural to press pause, rest and simply be with one another.

Spiritual direction offers a space that is unique and refreshing for weary souls. It can help people reorient intentionally toward God — which changes the way they engage their work, their friends and family, and their love for their neighbors.

To learn more: Spiritual Directors International provides a service to connect people with spiritual direction. Here you can search based on a number of criteria including the area where you live and any special interests. They highlight one-on-one direction, group direction, and retreat centers offering direction.

Liz Andrasi Deere is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Charlottesville, Va.