It’s not about Donald Trump. Nor did our current dis-unity start with him.

In his excellent book, American Nations, Colin Woodard shares helpful insights into what lies at the heart of much of our current public discontent: We began this way. Woodard continues his narration of our nation’s conundrum and ongoing experiment in American Character: A History of the Epic Struggle between Individual Liberty and the Common Good.

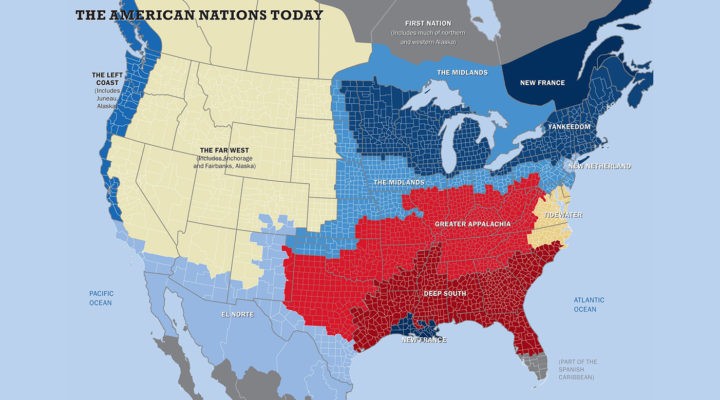

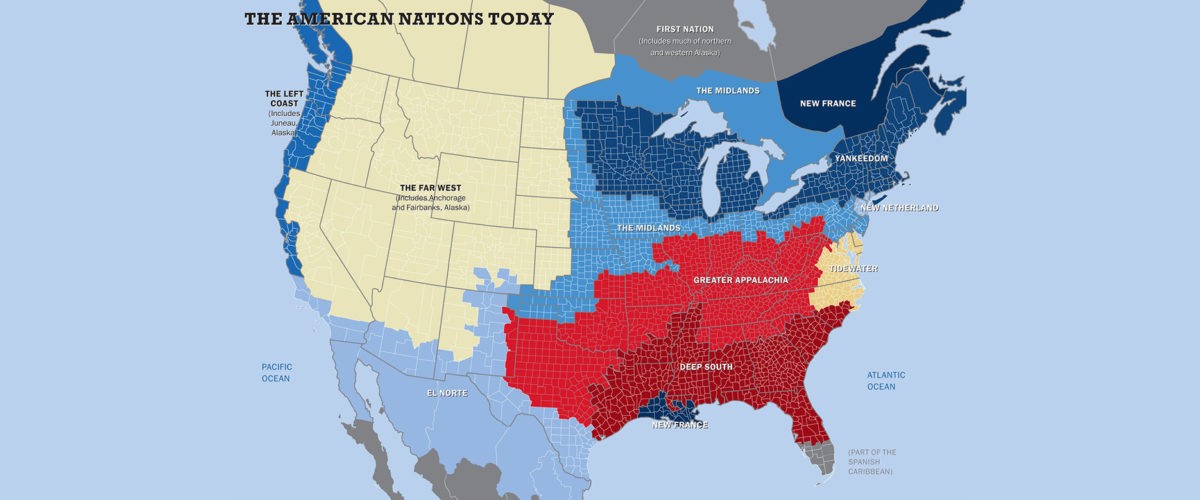

In both, he reminds us in clear, stark and well-delineated terms that lack of unity in our political system is to be expected. Our nation is actually a coalition of 11 separate and highly competitive nations. Especially the two most prominent, “Yankeedom” and “The Deep South,” have generated the preponderance of the fire and smoke over the years.

David Jordan

Often allied with “Tidewater” (mostly Virginia) and “Appalachia” (a large swath of middle and eastern America) the Deep South coalition views the world through a vastly different lens than the competing coalition of their northern and western counterparts.

Yankeedom emerges out of the Puritan, highly equitable world of New England. Usually allied with the Left Coast (California, Oregon and Washington) and New Netherlands (all the areas around New York City), the more northern and western alliance generally combats and detests much of what the Deep South coalition asserts (and vice versa).

Not just ‘liberal’ or ‘conservative’

Whether civil rights, America’s role in the world, war, the size and scope of government, taxes, the role of religion in public life, or abortion, these two large and highly influential regions of Yankeedom and the Deep South continue to be at odds. Some have even claimed that the Civil War continues through a variety of less violent but highly visible and audible forms.

In Woodard’s well-researched perspective, the widely disparate world views stem not from “liberal” or “conservative” perspectives as much as from the native origins of those coalitions. For example, the Deep South narrative portrays a national origin steeped in individual liberty. In truth, this liberty in the Deep South most specifically applied to wealthy landowners who were white, male and well-connected.

Appalachian culture, on the other hand, emerged out of the Scottish lands laid bare for centuries from English aggression. These poverty-stricken refugees settled among the lands from Western Pennsylvania all down and across the Appalachian Mountains to Southern Ohio and all the way to Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee and East Texas.

For them and the lands they settled, government was bad, outsiders were suspect, family (“blood kin”) remained tight and central, violence solved problems and the idea of a “common good” made no sense.

These settlers had little to nothing in common with the Deep South. In fact, they were looked down upon and scorned. Yet over the centuries of complicated interactions, Deep South perspectives, especially regarding race and views on government, have coopted much of these Appalachian descendants and their independent spirit.

The Common Good versus individual liberty

Generally, Yankeedom claimed and nurtured governmental policy based on the common good. It took a while. Witch hunts and persecution of dissenters aside, New England gradually evolved into a land of the melting pot. If you agreed to join their common venture, you were considered an equal partner worthy of education and full inclusion.

“This was the common good that would model the best of American egalitarianism.”

This was the common good that would model the best of American egalitarianism. As a foundation for decisions, projects and priorities, government was vital and good, while public schools and public libraries facilitated a level playing field. Taxes were important because they funded projects to cultivate equity and to nurture equality.

Individual liberty, on the other hand, rose in the Deep South out of an aristocratic perversion of John Locke’s philosophy. Equality below the coastal Mason Dixon line applied only to those who owned considerable property and who hobnobbed with the elite.

The Southern aristocracy of this “American Nation” originated from the sugar cane planters of British Barbados who began and migrated to Charleston in the late 1600s. For these inheritors of wealth, benefitting from the prosperous and indescribably cruel plantation culture of the East Indies, individual liberty was highly limited. It had nothing to do with the vast majority of those who would ultimately populate the Southern states.

For these rich planters in and around Charleston and the Deep South, to speak of equality for anyone other than the elite smacked of foolishness. Liberty was for those who owned the land, ran the plantations and controlled the society. The smaller the government, the better.

Westward migration

Woodard’s compelling case utilizes migration patterns and linguistic analysis of current American accents to illustrate an amazing trend. The westward migration from each of these cultures, especially from Yankeedom, the Deep South and Appalachian culture indelibly imprints a clear, stark reality upon the lands they settled.

“Vast differences birthed from disparate beginnings still reverberate across our land.”

Vast differences birthed from disparate beginnings still reverberate across our land. Any electoral map of recent years, including 2020, illustrates the point. The coasts are largely pitted against the heartland, the cities against the towns and rural areas. These culture clashes emerge not as the result of the current president or some new cultural phenomenon. The divisions so evident today began in our very beginnings.

The red heartland and blue coasts, the red rural areas and blue cities are historical people movements authenticating actual polling results and voting patterns. Deep South and Appalachian sentiments poke clearly through the data — calls for individual liberty and suspicions of big government; racial biases, white supremacy, and fear of personal freedom infringement (mask wearing and vaccine necessities) all fit well into the cultural categories Woodard describes.

Where to find unity

Will a Biden administration bridge the gap? Compromise, so essential for our political system to function adequately, does occur. And a fleeting unity in our American Experiment can happen. But in general, these times transpire as a matter of serendipitous common agendas. They tend to be advantageous only for those particular regions, and mostly last for the political moment. The alignment matters less about any new common vision and more about temporary regional satisfaction.

Yet hope still exists. It must. Dedicated lives have made a difference. Faith has changed hearts; hard work in the right direction still reaps ultimate rewards. The power of love continues to instill compassion, facilitate understanding, motivate action.

One life makes a difference

Say what you will about Martin Luther King, but our nation is different now because he lived and worked among us. More recently, John Lewis exemplified a brave life of strength, service and joy. His courageous dedication inspires still. Stacey Abrams weathered a harsh political loss to devote herself tirelessly to voter education and broadened voter registration. Her personal resiliency has changed the course of Georgia’s electoral history.

“Individuals can and do make a difference even in the face of history, voter suppression and trends that appear insurmountable.”

People matter. Individuals can and do make a difference even in the face of history, voter suppression and trends that appear insurmountable. Our American Experiment continues. And the tension lives: Work for the common good or stand for individual liberty?

Knowing some of our tumultuous, raucous and somewhat predictable stresses and strains can explain much of our current predicament. It also can, and must, inform all necessary efforts to heal our land and the lives so affected within it.

May God give us the wisdom to learn from our past. And in spite of our differences, may God grant us the fortitude to move forward, together.

David Jordan serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Decatur, Ga.