After the events of Jan. 6, I spent days not knowing what to think, much less what to write in a pastoral letter to my congregation. Since that day was Epiphany on the church calendar, for a while, I was tormented by that old familiar feeling that there was really no way to get away from Herod.

Despotic rulers are like that. They want your fear, your adoration, your loyalty — but they mostly just want to stay in control. Love him or hate him, it’s hard to quit Herod, to leave him behind, and he likes it that way. But leaving Herod behind is the only way forward.

John Inscore Essick

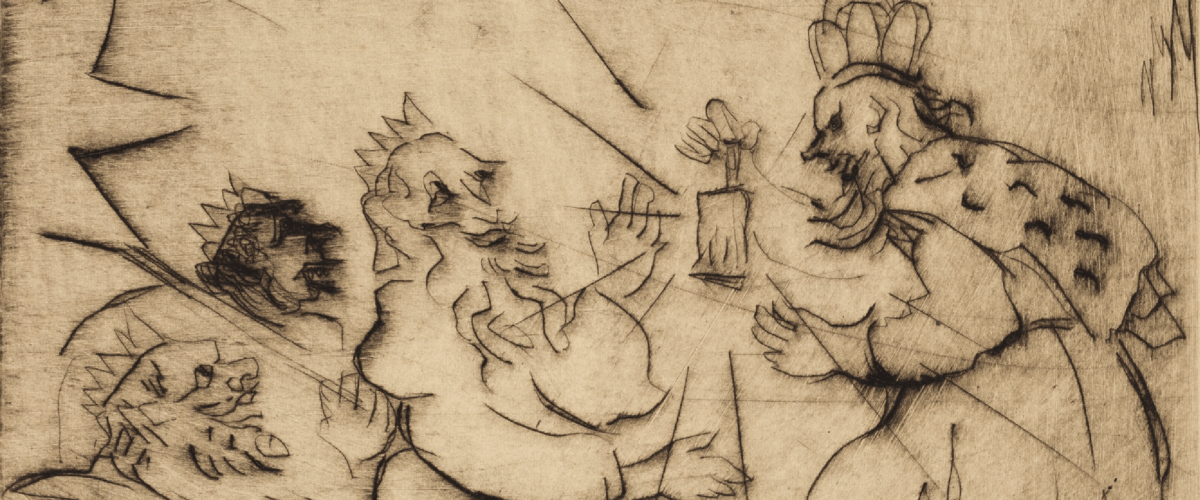

The Herod we meet in Matthew 2 is “at war with himself,” according to Stephanie Buckhanon Crowder, because a group of regal strangers from the East showed up in Jerusalem asking where to find the king who had just been born. The questions these magi were asking unsettled Herod and exposed his deep insecurity. Driven by anxiety and paranoia, he quickly concocted a plan to have the magi locate the child for him so that he could pay homage. Or so he said.

You see, Herod was frightened. And all of Jerusalem was terrified with him. He didn’t want to face painful truths about himself, his kingdom — nor did his people. So much of their life together was built on compromises and the violence and oppression that comes with living under imperial Rome’s thumb.

This is how Herods function. Herods force others to feel what they feel, to share in their anxiety, fear and dread. Matthew makes it clear that living under Herod’s rule was uncomfortable for one and all. There was no respite. No vaccine. No one — from the highest to the lowest — was at peace. Herod’s feeble façade of control was quickly and easily fractured by just a few simple questions from Zoroastrian astrologers from the East.

Little wonder, then, that this Herod of Matthew 2 saw others as either steps or threats — steps to greater power and prestige or threats to power and prestige. So, when the magi arrived and were interested in honoring not the king in Jerusalem but the child in a manger, Herod could only think opportunistically about how he could use these guests to secure his position and remove a potential threat.

Herod wants it all to run through him, and when it doesn’t — well, he’ll rant and rampage and flail and destroy and blame anything and anyone. For Herod is sensitive, mind you, extremely sensitive. He’s threatened by anyone who looks remotely threatening, whether that person be a baby born to poor parents in Bethlehem, an unarmed George Floyd begging to breathe to his last breath on a street in Minneapolis, or a broken and deeply confused Air Force veteran like unarmed Ashli Babbitt, who took her last breath on the floor of the Capitol building.

“Herods care only for themselves. And that is why we must join the magi in leaving Herod behind. We must.”

And although our Herods claim in public pronouncements to love and understand the broken and confused and preyed-upon in this world, it simply is not true. Herods care not for the young or Floyd or Babbitt or you, neighbors and friends across the miles, for Herods care only for themselves. And that is why we must join the magi in leaving Herod behind. We must. We must.

But it’s not going to be enough simply to walk away from him as if “ABH” — Anybody But Herod — will do. The wise travelers from the East didn’t leave Herod in search of just anything or anyone. No, they shed Herod’s deceit in search of the treasure that awaited them in Bethlehem.

Bethlehem is really where the true, good and just action is taking place. Bethlehem is where we go after leaving Herod. The future, thanks be to God, does not run through despots but through the child in Bethlehem, who, in Simeon’s words, is “a light for revelation to Gentiles” like the magi and like us and a “sign” that will be opposed and reveal the inner thoughts of many (Luke 2).

That is what Bethlehem holds if we leave Herod behind and travel in its direction: Light and revelation not fear and conspiracy. The voice of the Lord out of Bethlehem is strong enough, in the words of the psalmist (Psalm 29), to thunder over mighty waters, break the cedars of Lebanon, and shake the wilderness — and before that Lord, all things cry out “Glory!”

Our magi wisely left Herod to go worship in Bethlehem, but they did not do Herod’s bidding. In defiance of Herod, they went to their own country by another road. Were they frightened? Almost certainly. Were they confused? Probably. Regardless, wise ones know you don’t depart worship of the Messiah and run straight back to Herod. It’s a new day, and you’re on a new road.

We must resist the roads back to Herod. Wise ones know where home is and go there upon leaving worship. But they also return home changed, leaving Herod behind and carrying the news that the child in Bethlehem alone deserves our adoration, attention and gaze.

Remember, there isn’t just one Herod. In fact, it’s easy to get mixed up about which Herod we are talking about in the Bible as there are at least six figures by that name.

“There have been so many Herods since this Herod of Matthew 2. And we live in a world of Herods still.”

But really, all the Herods were the same. There have been so many Herods since this Herod of Matthew 2. And we live in a world of Herods still.

Sure, one of our Herods was exposed Jan. 6 as crosses and Christian flags were flown alongside flags of the Confederacy and a lynching station set up at the symbolic heart of this democracy. But we should remember that there are still more Herods out there. And that we have proved to be really bad at recognizing the Herods among us and the Herods within us.

Yet our response should be the same each and every time we come upon a Herod: Leave. Run to Bethlehem. Worship. Return home changed.

Even after kneeling before the Son of God, though, it can still be difficult to quit Herod. It probably was difficult for the magi to risk their lives to defy him. Love him or hate him, it’s hard to leave Herod.

Some of us struggle to leave Herod behind because he makes us feel good about ourselves. He makes us feel justified (falsely, I should add) in proudly pronouncing that we are not like him and not among those who wear his hats and wave his flags because they finally feel like someone has heard them and understands their concerns.

“Others of us will struggle to quit Herod because he makes it easier for us to belittle and restrict the freedoms of those who are not like us.”

Others of us will struggle to quit Herod because he makes it easier for us to belittle and restrict the freedoms of those who are not like us. Herod helps us feel justified in blaming (falsely, I should add) migrants, foreigners, Black Lives Matter, and LGBTQ citizens for the many complicated problems we face.

Jan. 6 presented more revelatory epiphanies than I was prepared to handle. And I still don’t know exactly what to make of those epiphanies. One epiphany a day is usually more than enough. But then again, maybe there really was only one Epiphany I needed, and it was the oh-so-vivid reminder that I confess “Jesus is Lord.” I had to remind myself that Jesus is Lord over and over on that day and every day since. “Jesus is Lord” is a political statement that stands on and above all others.

Jesus is Lord — not Herod. Not duly elected President Trump; not his duly elected successor, Joe Biden; not the Senate; not the House of Representatives; not the courts; not the voters; not the cops; not America; not you; and certainly not me.

If Jesus truly is Lord, then it’s well past time we leave our obsessions with Herod behind and, like the magi, head back to the country we love by way of Bethlehem.

John Inscore Essick serves as associate professor of church history and director of the Rural Ministry Program at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky in Georgetown, Ky. He also serves as co-pastor of Port Royal Baptist Church in Port Royal, Ky.

Related articles:

Denominational leaders denounce Capitol violence while evangelicals offer mixed responses

Toxic masculinity, 24-hour news and complacency fed the Jan. 6 riots | John Jay Alvaro

Broken churches, broken nation: Will evangelicals ‘recalculate’ or rebel? | Bill Leonard

It’s past time to admit the hard truths behind the Capitol riots | Wendell Griffen

Christian symbols and sedition at the Capitol: The church has work to do | Rhonda Abbott Blevins