An old idiom, usually attributed to Oscar Wilde, says that irony is wasted on stupid people.

But not everyone who fails to appreciate irony is a mindless dolt. Some of them are quite clever, aiming their malformed wit in the direction of treachery but unable to withstand the wiles of irony.

Sometimes, irony is wasted on the sophists.

In a recent New York Times column, Katherine Stewart recounts Sen. Josh Hawley’s strange crusade against “Pelagianism.” According to the Missouri lawmaker, the Pelagian error — an insidious heresy that teaches that we are joined to Christ by our wills rather than by grace — is inscribed in the unrestrained social behaviors that blossom in a liberal democracy. It’s not difficult to imagine which behaviors he has in mind. Hawley has a peculiar axe to grind against the “sexual revolution,” and he opposes legal protections against workplace discrimination on the basis of gender identity.

Sen. Josh Hawley

From Hawley’s perspective, the unmitigated freedom to choose how we live our lives is a mutation of the Pelagian error, a grand elevation of the will that lies at the root of America’s moral decline. What we have as a result, he argues, is an atomized culture that undercuts the project of national cohesion, a wayward society that neglects social bonds and local connections.

For people like me who have their own criticisms of liberalism (the political philosophy, not the partisan category), Hawley’s arguments can sound like the polemics of a kindred spirit at first blush. It is true, after all, that the loss of communal bonds has wreaked havoc on the lives of everyday Americans, leaving them in a state of isolation and despair. And it is also true that the dissolution of local traditions — the practical stories that tell us what human life is for — has led us to a state of affairs in which people conceive of morality in terms of mere personal preference. Indeed, how can we effectively foster ethical formation in these bleak conditions?

But in light of Hawley’s deceitful and destructive behavior in recent weeks, we have good reason to probe the merits of his political philosophy — both for the sake of sharpening the distinction between his attractive rhetoric and contemptible politics, and to present a case study in nationalism and nihilism.

Let’s take a look at both, with a proper critique of Pelagianism in view.

First, Hawley’s nationalism: In 2019, Josh Hawley delivered a keynote address at the National Conservatism Conference, a coming-out party for the “new nationalists.” According to former Netanyahu adviser and conference organizer, Yoram Hazony, the assembly marked an “independence day” from the conservative fusionism of the William Buckley era. The new objective, he claimed, is to restore the “Anglo-American” traditions of our past.

Amy Wax

The meaning of Hazony’s coded language (“Anglo-American”?) becomes clearer in light of Amy Wax’s speech, in which she bases her immigration policy on the view that “our country will be better off with more whites and fewer nonwhites.”

Having said the quiet part out loud, Wax provides a lens for interpreting Hawley’s own coded presentation, which castigates “cosmopolitanism” no less than 12 times. Pardon the alarm bells, but a speech that mourns the demise of national roots while excoriating “cosmopolitan elites” conjures the memory of an old antisemitic epithet used in Germany and Russia: “rootless cosmopolitans.” Whether or not Hawley was being consciously antisemitic (Hazony is Jewish), his language still functions as a dog whistle, and it reveals strong prejudice against foreign cultures while prescribing national allegiance.

“She bases her immigration policy on the view that ‘our country will be better off with more whites and fewer nonwhites.’”

As Stewart recounts in her Times column, Hawley’s solution to the problem of rootlessness — a problem that starts with Pelagian individualism at the expense of collective identity — is to bring the political realm under the authority of the Christian faith. His Christian nationalism entails the existence of a paternalistic class of spiritual elites who can train the will of the citizenry, a view that resonates with the main principle of Catholic Integralism — namely, that the temporal realm should be subordinated to the spiritual realm.

Sohrab Ahmari

Hawley also finds an ally in First Things, a right-wing Christian magazine whose editor, Rusty Reno, was another keynote speaker at the National Conservatism Conference. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the authors of First Things’ manifesto on Christian nationalism, echoes the Integralist point of view when he dreams of “defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.”

Christians do have a vision of the Highest Good (per Ahmari), but it has absolutely nothing to do with nationalists’ dreams of recovering “Anglo-American” values or imposing policies that obstruct the presence of nonwhites — an outcome Ahmari himself rejects.

As followers of a crucified Jew who bears witness to God’s irrevocable election of Israel, we certainly have no interest in scapegoating “rootless cosmopolitans.” Rather, we defer to John of Patmos, who envisions a great multitude from every nation, tribe, people and language.

Speaking of roots, the idea that nation-states are the wellspring of local community is historically dubious. When Hawley wrote his college honors thesis, he contended for Theodore Roosevelt’s view that government can foster communitarian sentiments. But as the theologian William Cavanaugh has argued, “Nation-states are built on the destruction of local forms of community. Nation-states arose by the absorption of authority and privileges previously belonging to municipalities, ecclesiastical bodies, guilds, clans and nobles.”

Indeed, the erosion of civil society is largely attributed to national allegiance, which replaces the particular bonds of local communities with broader, Völkisch bonds — like whiteness. Nationalism and its racial corollaries, then, are contrary to the Highest Good, which is better represented in the second century Letter to Diognetus, where the author describes Christians “liv(ing) in their respective countries, but only as resident aliens” because “every foreign territory is a homeland for them, and every homeland a foreign territory.” To Hawley, that probably sounds like rootless cosmopolitanism.

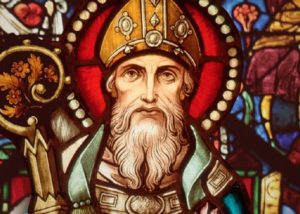

Stained glass depiction of St. Augustine

I wonder what St. Augustine, the archnemesis of Pelagianism, would say to Hawley. After all, one of the factors that drove Augustine’s response to Pelagius was the issue of elitism: If the human will is the catalyst of salvation, who other than a few virtuosos can achieve eternal bliss? And if these spiritual aristocrats overestimate the pristine character of their own wills by presuming to adjudicate the “Highest Good” for the rest of us, what kind of power imbalance could arise from that? What would happen if a small class of theocrats tried to train the collective will of an entire nation?

When speaking of Pelagianism, Hawley is not wrong to draw a connection between salvation and politics. But the way he does so is precisely backward. Whereas Hawley sees his political paternalism as a response to Pelagianism, it should actually be seen as a manifestation of Pelagianism. After all, a proper doctrine of grace has no room for spiritual elitism, because it universalizes — or dare I say, democratizes — sin and grace.

“A proper doctrine of grace has no room for spiritual elitism, because it universalizes — or dare I say, democratizes — sin and grace.”

In the words of St. Paul: “Just as one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all.” The Apostle does not make an exception for Josh Hawley, whose undemocratic politics corresponds to undemocratic doctrines of sin and grace. Indeed, by elevating himself above the realm of sin’s universal tyranny, he deceives himself.

But self-deception is a fundamental characteristic of Pelagianism, and the political ramifications are dangerous. That brings us to Hawley’s nihilism.

What the Missouri lawmaker thinks he wants is a philosopher-king. But ever the dilettante, he has no idea what that means. In Plato’s Republic (where the idea of philosopher-kings originates), the underlying question is this: What happens when philosophy and political power are divided?

In Book I, Thrasymachus drives a wedge between political will and philosophical wisdom when he says that justice “is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger.” On this view, the ruler’s will is a rudderless ship with no recourse to truth, beauty and goodness. According to theologian D. Stephen Long, whose book on truth-telling should be studied by every congregation in America, this means that “the kind of government that orders society is irrelevant.” All that matters is “winning” by any means necessary — including manipulation, lies and coercion.

For Plato, the whole point of installing a philosopher-king is to place the more “appetitive” and “spirited” segments of society (soldiers and workers) under the governance of a rational agent. This tripartite structure of the city stands in an analogical relationship to the tripartite structure of the soul, where emotions and desires are governed by wisdom and rationality.

Put simply, the idea is to subordinate the will to truth. Without wisdom and truth-telling, the soul and the city become violent networks of brute will, where “truth” is whatever a demagogue wills to be true. As Long goes on to say, this is exactly how the philosopher Friedrich Jacobi defined the term “nihilism” when he coined it in the 18th century: it is the infinite assertion of self-will, untethered from any notion of truth.

“By doubling down on the Big Lie of voter fraud even in the aftermath of the Capitol insurrection, he eschews the truth and exerts his will to power.”

Hawley thinks he wants a philosopher-king; but in fact, by doubling down on the Big Lie of voter fraud even in the aftermath of the Capitol insurrection, he eschews the truth and exerts his will to power.

Indeed, Hawley is precisely the kind of person Plato was worried about. He wants the Platonic hierarchy without the Platonic wisdom, the governance without the philosophy, the appetitive and spirited faculties without the rational faculties. Hawley thinks he’s Socrates, but in fact he’s Thrasymachus. He thinks he’s a philosopher, but in fact he’s a sophist with nary a sense of irony.

What business does he have in reproaching the liberal order for its “Pelagian” confidence in the will? By subordinating the truth to his own will to power, this imposter is a nihilist and Pelagian par excellence.

In terms of governance, Christians need not choose between Hawley and Plato. Both men want rulers, but we worship a king who deconstructs the whole paradigm of kingship altogether. Our philosopher-king is also a priest-king, a lowly Nazarene who did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but rather emptied himself and took the form of a servant.

The Highest Good, then, precludes the coercive act of ordering the public square to itself, because the Highest Good does not lord itself over others.

Rather, in the words of Isaiah, the government will be on his shoulders. And upon those shoulders are the heavy wooden beams of a Roman cross, on which he is enthroned as a king who serves and suffers and salves.

Unless our wills are subordinated to this image of what’s true and beautiful and good, we deceive ourselves — and the truth is not in us.

Matt Dodrill serves as senior pastor of Pulaski Heights Baptist Church in Little Rock, Ark. He is a graduate of Calvin College and Duke Divinity School.

Editor’s note: This piece was modified from its original form in the 14th and 15th paragraphs to more clearly articulate the stated position of Sohrab Ahmari against racism.