A decade-long disagreement over how Southern Baptists fund church planting and missions in North America is coming to a head and threatens the sanctity of the denomination’s spirit of cooperative giving.

The result: State conventions outside the South are reducing their contributions to the denomination’s highly revered Cooperative Program because the SBC is sending them less missions support money through partnerships.

The underlying threat is a response to restructuring of the denomination’s domestic missions agency in 2010. That is when Southern Baptists approved a new mission statement for the North American Mission Board and pegged their hopes on its ability to stem the denomination’s steady drop in membership, baptisms and giving to missions through aggressive church planting.

That church planting must be a priority is not in dispute. The disagreement concerns how church planting should be done and whether the national body should work independently in states without coordinating with state and regional Baptist conventions.

That church planting must be a priority is not in dispute. The disagreement concerns how church planting should be done.

The specific focus of the revolt is NAMB’s abandonment of long-time Cooperative Agreements, which pulled $51 million in annual funding out of all 42 state and regional conventions. That action reversed nearly 60 years of a shared funding program that fueled much of the denomination’s growth from the 1950s as it spread west and north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

The current uprising finds its strongest voice in the non-Southern states, where Southern Baptists are not as prevalent. Leaders in these state conventions claim NAMB has cut them out of longstanding partnerships in missions and church planting and has adopted more of a “franchise” approach.

NAMB trustees at a meeting (Photo: NAMB)

For its part, NAMB staff leadership and trustees don’t deny there has been a radical shift in missions strategy. They have been clear and consistent in their vision. The shift not only is necessary but has been endorsed by the SBC in annual session, leaders contend. NAMB has not defunded mission work in states, the explanation says, but has reappropriated funds previously channeled through state conventions for nearly three-quarters of a century — and on which those state and regional conventions came to depend.

A letter from six state executives

This simmering disagreement burst into full public view in August 2020, when state executives from six state conventions — California, Hawaii, Ohio, New Mexico, Alaska and the Northwest (composed of Washington, Oregon and North Idaho) — figuratively nailed their 95 theses to the doors of NAMB in Alpharetta, Ga., and the SBC Executive Committee in Nashville, Tenn.

Those six later were joined by another nine state executives. If those 15 close ranks, they would represent slightly more than a third of the denomination’s conventions — but not of the SBC’s total membership. What has emerged is a loose confederacy that could unravel the “rope of sand” by which Baptists have funded their global missions and evangelism outreach since 1925.

The signers declared a list of concerns about the abandoned partnership strategies and cited five options they could pursue if their concerns are not addressed:

- Declining acceptance of new, increasingly restrictive agreements with NAMB.

- Retaining a larger portion of CP gifts for ministry in their states rather than sending the full portion to the national body.

- Designating CP dollars to specific SBC agencies or ministries, therefore bypassing NAMB.

- Reducing Annie Armstrong Easter Offering giving to allow “a more robust state missions offering.”

- Creating state-affiliated partnerships for more effective and cooperative ministry.

Several states already have sought ways to skirt the NAMB defunding by keeping a greater share of offerings in their states to replace what has been lost.

NAMB’s trustee leadership promptly responded to the six state convention executives with their own letter, explaining why they believe the new strategy is essential: The board “wholeheartedly supports President (Kevin) Ezell and our staff in the direction NAMB is taking in fulfilling our ministry assignments with churches, associations and state conventions.”

“You have correctly identified that we are more focused (centralized) and directive in our strategies, personnel and funding.”

“You have correctly identified that we are more focused (centralized) and directive in our strategies, personnel and funding,” the response continued. “We’re not sure you could make a more complimentary accusation of us! NAMB trustees expect our leaders to develop and implement strategies that accomplish our ministry assignments and to then fund those strategies specifically.

“We take very seriously the task of being good stewards of the funds given to NAMB by SBC churches through the Cooperative Program and the Annie Armstrong Easter Offering. We certainly do and will continue to assess and evaluate all the planters and all the personnel we fund. We have no intention of delegating these responsibilities to any ministry partner.

“This is not a lack of cooperation or partnership; it is our way of stewarding the resources we invest in NAMB strategies. Many ministry partners, including our three churches, have found this to be incredibly helpful and effective in identifying and retaining the best candidates for the important roles that NAMB is funding. We believe if you will give it a chance you will find the same to be true.”

Alaska decision elicits strong rebuke from Nashville

In September 2020, just 45 days after the six state executives’ letter was posted, Alaska Baptists voted overwhelmingly to withhold allocation of future Cooperative Program funds earmarked to NAMB. The motion will go into effect with the 2022 budget if approved by state convention messengers this September.

The motion called for funds to be “retained in Alaska and designated for the Valeria Sherard State Mission offering until such time there is a collaborative, cooperative and mutually agreed upon strategy.”

Ronnie Floyd

Ronnie Floyd, president and CEO of the SBC Executive Committee, charged back through Baptist Press, saying the Alaska action represents “a unilateral breach of a 95-year system as our most trusted funding mechanism.” He then added, “The Cooperative Program is not a cafeteria plan.”

NAMB President Ezell, speaking also through the news service, said he “has been and remains willing to participate” in meetings to resolve the differences. He also said NAMB remains fully committed to funding church planting and evangelism efforts in Alaska.

The point in question is who will do the planting — a national agency nearly 4,500 miles away or the state convention through its own church planting network.

Randy Covington, executive director of the Alaska Baptist Resources Network, begged to differ with Floyd’s interpretation. “What was mistakenly described as a ‘unilateral breach’ was, in essence, an effort by Alaska Baptists to say we want our voice to be heard. If NAMB chooses to concentrate their funding on large cities that are already being reached (in the Lower 48 states), we cannot abdicate our responsibility to engage the unreached rural communities in Alaska with the gospel. That’s our calling; that’s on us as Alaska Baptists.”

Randy Covington

Covington noted that his sparsely populated state is so strapped for funds that in 2018 it reduced its percentage being forwarded to the national Cooperative Program from 34% to 20%. “If we’re going to reach our state for Christ, we’re going to have to keep more money at home,” he said at the time.

That is the growing sentiment among many of those in the SBC-related conventions outside the South.

However, the rebuttal from NAMB’s trustee chairman and two vice chairmen could not be clearer. The officers stated there is “not a lack of cooperation or partnership; it is our way of stewarding the resources we invest in NAMB strategies.”

In January 2021, Floyd responded to the letter with what he termed the Executive Committee’s “final response” which said his office — the highest ranking in the denomination — is only charged “to act in an advisory capacity” (his emphasis and bolded word) in questions of cooperation between entities and has no power other than intermediary.

In effect, he said his hands were tied.

The letter concluded with a lengthy request for the non-South conventions and NAMB to work out their differences in a spirit of mutual cooperation. The response from state conventions: Highly unlikely.

In a response solicited by Baptist Press, Northwest Baptist Convention Executive Director Randy Adams said the document “may be the final response of the (Executive Committee) but it may not be the final response of Southern Baptists. The response was dismissive and damaging to the cooperative partnerships that built the SBC.”

Randy Adams

Adams, who is one of four candidates for the presidency of the SBC this summer, noted that in a Zoom meeting prompted by the letter, the Executive Committee officers and Floyd “heard 12 state convention executive directors say that NAMB, under Dr. Kevin Ezell, has not kept its commitments, has a record of failure, and is not trusted. For over two hours they heard story after story of broken commitments and utter disrespect from NAMB leadership, all of which has contributed to steep decline in the SBC.”

He ended by saying: “This is not leadership. This is an abdication of leadership.”

Some state conventions have returned to the negotiating table and received limited funding, with those meetings heralded by NAMB as signs of progress. But those convetion leaders worry that in the interim NAMB is suddenly cooperative only due to the pressure it is receiving. They ask what happens when they lose their bargaining chips and no longer have leverage.

The largest conventions in this group — California and the Northwest — say they have no faith that NAMB will not break future agreements as freely as those in the past. Others share the sentiment but hesitate to go on the record while funds are temporarily being restored.

That logjam is where the dispute rests today.

Attempts to stop a shrinking denomination

Today’s problems and NAMB’s decade-old empowerment arise from Southern Baptists’ attempts to reverse their numerical decline. That desire centers around three critical events: the so-called “Conservative Resurgence,” which from 1979 to 2000 rooted out moderates and their perceived drift to the left; the Covenant for a New Century (1995) which, again noting an impending-but-not-yet-there decline, launched a massive restructuring of the denomination with the creation of NAMB; and the Great Commission Resurgence Task Force (2010), which restructured NAMB and centralized its power — fueled by pulling $51 million out of state convention partnership budgets and giving it to the suburban Atlanta agency for direct use.

The 1980s purge came at great cost. By the time it was over, 1,900 churches had left or distanced themselves from the SBC. New denominational leaders — armed with a literal interpretation of Scripture — said the convention was poised for an overdue revival.

In 1996, with the denomination on a statistical plateau and leadership still fearing a decline, a massive restructuring was approved by messengers to the SBC annual meeting. The Covenant for a New Century reduced 19 SBC entities to 12 and freed up resources for greater evangelistic outreach. NAMB became the successor to the SBC Home Mission Board.

Right out of the gate, NAMB was flush with the inheritance — a net savings of $30 million to $37 million in the first five years

Right out of the gate, NAMB was flush with the inheritance — a net savings of $30 million to $37 million in the first five years — it received through the restructuring. The denomination once again was poised to reverse its decline.

The long-promised downturn did not arrive until 1998, when the denomination faced its first membership setback in the modern era. But a Baptist Press article dated June 10, 1999, attributed the loss of members not to bad theology but to a national decline in the Anglo birthrate — with acknowledgement of the denomination being largely Anglo in composition.

It took another decade for the reality of the denomination’s numerical decline — with baptisms at the lowest level since 1972 – to bear fruit in more restructuring.

Daniel Akin

In 2009, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary President Daniel Akin launched perhaps the first salvo against the denomination’s “bloated” agencies and state conventions. In an April 16 chapel address titled “Axioms: A Conservative Resurgence Manifesto,” he said the denomination was composed of sluggish agencies that needed restructuring.

“The rally cry of the Conservative Resurgence was, ‘We will not give our monies to liberal institutions.’ Now the cry of the Great Commission Resurgence is, ‘We will not give our money to bloated bureaucracies.’”

The “bloated bureaucracies” reference was not taken kindly by state convention executives who felt they were being blamed for the national body’s decline. Yet a leaner denomination was the key to a brighter future, Akin assured his listeners.

Picking up on the theme two months later, then-SBC President Johnny Hunt appointed a study committee to address the need for a “commitment to a more efficient convention structure.” The new structure would, in theory, reverse the denomination’s walk down the slippery slope of numerical decline facing nearly every other religious body in America.

Akins’ earlier statement about denominational ineffectiveness bore fruit when the group — with the seminary president as a member — issued its preliminary report in February 2010.

The document was as controversial as Akins’ original chapel address, due primarily to the call to eliminate NAMB’s Cooperative Agreements with state conventions. That amount, pegged at $40 million and preserved for the state conventions in the earlier Covenant for a New Century document, had now grown by $11 million. The committee agreed those funds, now at $51 million, would be pulled from state convention budgets.

The “bloated bureaucracies” reference was not taken kindly by state convention executives who felt they were being blamed for the national body’s decline.

In later statements, NAMB said changing those partnership agreements actually would free up about $62 million total in all that NAMB contributes to state work. It also said more than three-fourths of all the money involved (about $48 million) would be taken from Canada and 36 “pioneer states” now referred to as the “non-South states.”

Once again, NAMB was inheriting a cash infusion, this time clawed back from state conventions. The states, feeling under siege, immediately marshalled their forces to keep the funds, which they believed were largely responsible for the denomination’s growth. In the Covenant for a New Century, seven national agencies took the brunt of the blame when they were shuttered; now the state conventions felt like they had become the whipping boy for the denomination’s problems.

If adopted by messengers to the SBC annual meeting in June 2010, the document would radically reshape SBC culture and empower the denomination’s church planting ministry to work independently of states in placing missionaries on the field.

Non-South state leaders spoke loud and clear during the four-month discussion period from February to June. Sides were clearly drawn between all the conventions and the task force report.

Albert Mohler

Committee member Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and a member of the previous committee that had created NAMB, hailed the Cooperative Agreements as “outdated and confusing.”

“We are calling for the North American Mission Board to concentrate on its task assigned by the Southern Baptist Convention — and to do so through the direct appointment of missionaries and church planters who are accountable to NAMB and deployed according to its national priorities,” he said. Cooperation with state conventions was key, he stressed, but what “cooperation” meant was not defined.

But on June 3, just one week before the SBC vote, the denomination’s highest-ranking staff leader, Morris Chapman, said the committee overstepped its charge and accused them of mission creep in their original assignment.

He stated he had never seen any such committee “that has brought a report … that has so challenged the fragile nature of the cooperative relationships that make up the fabric of the Convention as this Report … . I have not seen anything framed more appealingly that has such potential to damage our cooperative work than this document.

“It is clear that the words in the motion ‘work more faithfully and effectively together’ did NOT (his emphasis) instruct the task force to consider ways to terminate cooperative agreements between the North American Mission Board and the states … or elevate designated giving to Convention ministries by giving designated giving an attractive and compelling name.”

Chapman continued: “To argue that most of the components proposed by the GCTF are within the parameters approved by the 2009 convention in Louisville, Ky., is at best a long stretch and at worst a leap in logic.”

Johnny Hunt making the recommendation from the Great Commission Task Force at the SBC annual meeting in 2010. (Photo: Baptist Press)

The following week, what was potentially the most far-ranging restructuring of an agency in the history of Southern Baptists was approved by a hand vote of the 11,000 messengers. With no paper ballots cast in the highly controversial matter, there was no way to know if messengers voted 80-20 or 50-50.

Messengers placed their trust in the selling of the report by Hunt, who commissioned the task force, and Floyd, who was serving as chairman of the SBC Executive Committee and who had chaired the committee by appointment from Hunt. Hunt has since joined Ezell’s staff to lead NAMB’s evangelism and leadership group, and Floyd now serves as the highest-ranking officer in the denomination and is charged with defending the reorganization while trying to keep the vast denomination together.

As they disbanded, the task force voted to seal details of their deliberations for 10 years — and then extended it by another five years — meaning the details may be unsealed prior to the annual meeting in 2025. The next four years will see whether or not the group’s work brought the long-expected turnaround or a fracturing of cooperation.

What is a Cooperative Agreement?

Carlisle Driggers is a student of Southern Baptist history because he lived through the denomination’s explosive growth of the mid-20th century and worked for the denomination as well. Now retired, he remembers how stunted the denomination’s growth was up until the 1950s.

Carlisle Driggers

As Baptists caught the vision of reaching beyond their Southern stronghold, they needed a plan to help those moving into areas with lesser evangelical witness. The end of World War II saw soldiers returning home, getting married and starting families in far-flung environs outside their Southern homeland.

Finding no evangelical church like they remembered back home, they began their own with little or no training. The Cooperative Agreements — funded with Cooperative Program monies disbursed through the Home Mission Board — were created to help those fledgling congregations and state conventions.

“Almost overnight, the agreements transformed the Southern Baptist Convention from being a regional faith group into a national denomination. Until then, we were barely known outside the Mason-Dixon Line; the agreements changed all of that,” Driggers recalled.

The new funding channel gave the embryonic state and regional conventions a fighting chance to survive the odds in cultures that, if they were not hostile to the gospel, were at least indifferent. As a young pastor, Driggers remembers how his own ministry changed after the agreements were implemented in West Virginia.

“It was like putting fertilizer on struggling crops that just needed a break to produce a harvest,” he said. “We were struggling with weak churches that didn’t have many, if any, resources to do ministry and, to be honest, still don’t today. We were able to use funds and train church leaders who in turn trained their laity.

“Up until that point we were as lost as a dog in the woods, but the Cooperative Agreements gave us the map to a better future.”

“It gave us outreach tools we never knew existed or could afford so we could reach our neighbors. Up until that point we were as lost as a dog in the woods, but the Cooperative Agreements gave us the map to a better future.”

Ernest Kelley, a retired executive leader from the Home Mission Board, recalls those early days but from the administrative side.

“The beauty of the agreements is that they gave state convention leaders confidence that they would have a monthly check coming in that would be spent on specific ministries, previously agreed on between the state and the HMB,” he said. “It wasn’t entirely free money because it was audited to assure it was being used as agreed upon, but we respected the autonomy of each state to know better how to spend the funds than we did in Atlanta.

“We saw ourselves as enablers rather than controllers,” he explained. “Bilateral cooperation was always the goal, and even with our differences we were able to work together with full transparency.”

In the eyes of the SBC’s NAMB reformers, that kind of partnership over the vastness of the nation inevitably led to “bloated bureaucracy” that needed to be replaced by a more centralized approach to domestic missions and a laser focus on church planting above all else.

Ezell carrying out a plan created by others

Kevin Ezell

To be clear, current NAMB President Ezell was not part of the Great Commission Task Force and was not hired until three months after the report’s adoption. He inherited a bilateral process where NAMB and state conventions jointly funded missionaries, but the die had been cast by the Great Commission Task Force report the summer before he took the helm.

Before the shift to a more centralized approach, the Cooperative Agreement formula typically was a 60/40 split in funding domestic missionaries and church planters. NAMB payed the larger share of a missionary’s compensation plus health insurance costs. The agreements were just one part — but a highly important part — of NAMB’s inherited structure that had been protected by the Covenant for a New Century.

The Great Commission Task Force changed all that.

NAMB’s mandated new focus on increasing the portion of its own budget going to church planting from 28% to 50% was a mammoth undertaking. After just 12 months, the Christian Index, state paper for the Georgia Baptist Convention, reported the percentage already had reached 42%. This change eventually would result in phasing out the majority of NAMB’s 3,500 career missionaries scattered across 56 different ministries that encompassed much more than just church planting.

NAMB declined to respond to a request asking if it had reached or exceeded the mandatory minimum 50% threshold.

Through NAMB, the SBC for many years supported ministries with the deaf, Native Americans and a broad representation with the nation’s exploding ethnicity, as well as feeding the hungry and encouraging congregations in their own local ministries. NAMB’s new focus was reduced to three areas: evangelism, church planting, and compassion ministry.

NAMB’s new focus was reduced to three areas: evangelism, church planting, and compassion ministry.

In addition, nearly 100 staff positions, more than 25% of NAMB’s corporate workforce, were eliminated in Ezell’s first 90 days.

That radical shift freed up funds and implemented a business model focused on hiring short-term church planters. The new hires were not to be NAMB employees in the historic sense and were to receive funding of about $1,200 monthly on three- to four-year contracts, after which it was expected the new churches would be self-supporting.

NAMB funds also have been used to purchase 109 pieces of real estate in targeted areas, providing housing for a rotating cast of church planters and their families assigned to the area. NAMB leaders have said they hope eventually to own 200 pieces of property, but a spokesman declined to identify states where the properties are owned or the number of properties in any given state.

From California to New England, the story is the same

The primary concern among non-South state leadership about the new approach is that NAMB has unilaterally and systematically eliminated partnership between the two entities.

Over the past decade, partnership has moved from jointly funded field personnel — including funding for associational directors of missions to ministries to migrants, evangelism, and church planting — to NAMB supporting primarily its church planters, who often have no relation to the state and regional conventions. In fact, sometimes state convention leaders have no idea where NAMB has placed church starters in their states.

Bill Agee

Bill Agee, state executive director in California, expressed concerns that are common among his peers, especially in non-South states.

“We in California are one of, if not the largest, mission fields in the country with 40 million people in our state,” he explained. “Between 32 and 35 million people do not know Jesus as their Savior. We need help and felt like we used to have it through the Cooperative Agreements before the task force dismantled them.

“For instance, in partnership with NAMB, California led Southern Baptists in 2018 and 2019 in the number of new church plants. California also led in 2018 in year-over-year baptism increase.

“Then we are informed in 2020 that the funding for evangelism would cease and NAMB would be taking over all church planting, which is unacceptable to California,” he said.

Church planters who did not want to work exclusively under NAMB or wanted to serve in an area that was not a NAMB priority were hampered, Agee explained. Now, as a result of the new policy out of NAMB, the SBC supports mission personnel in or near only three major cities in California. This is an intentional part of NAMB’s national strategy but it does not coordinate with many of the state conventions’ strategies.

“There are churches that need to be started all over the state that do not fit NAMB protocols.”

“There are churches that need to be started all over the state that do not fit NAMB protocols that we as a convention have stepped in to help,” Agee said. “As a result, California Southern Baptists now support more than 25 church plants through the California Funded Church Planting System that are funded by the state and other supporting churches. None of these are supported by NAMB.”

Agee, like other non-South execs, is upset with how NAMB says it is putting millions of dollars into the state but without showing how much or where it is being used. And NAMB does not make clear to donors that those monies are not going through the former partnership channels with state conventions, the state executives claim.

As a result, state executives say cooperation has ceased to exist — largely because the Great Commission Task Force did not understand the value of the Cooperative Agreements. And they believe the lack of transparency about where and how the funds are being used demands an audit.

State executives agree it would all be so much easier to understand if Ezell, as president, would be more open about what has transpired.

Ezell was provided numerous questions for this article and had agreed to an interview that instead was cancelled the day it was to occur.

Instead of that scheduled telephone interview, he issued a written statement: “I have always believed that Southern Baptists are at our best when we work together, and that is our goal at NAMB. Over the last several months I have had the opportunity to meet with most of our state partners either individually or in groups. We are thankful that we have a healthy relationship with the overwhelming majority of them. My focus is to be the very best steward of the resources that God and Southern Baptists have entrusted us with, and that means investing them in a way that will ultimately allow the largest numbers of people to hear and receive the Truth of the Gospel.”

One of the questions a NAMB spokesman had been asked separately was to clarify the number of church planters in each state. Ezell’s statement did not address that question, and the spokesman did not offer a reply. NAMB never has reported that number in the 10 years since its restructuring.

States: No accountability or transparency

Throughout leadership of the non-South states, virtually all agree that NAMB’s new approach has no accountability or transparency and there is no hope that will change. That is why the executives feel nothing will come out of Floyd’s January plea for cooperation when NAMB, especially through its trustees, refuses to acknowledge the problem they have named.

State execs charge that NAMB’s trustees have lost their sense of accountability to the men and women in the pew for whom they hold the agency “in trust.” Instead, they say the trustees see their role more as a firewall to protect the agency at all costs.

While their own books always were audited to be sure funding from the Cooperative Agreements was properly accounted for, state leaders now want to know who is auditing NAMB. A forensic audit detailing that information, not a cursory statement from an auditing agency favorable to NAMB, is what they say is needed. Even a website promoting this idea was launched in the fall of 2020.

Mike Ebert

Regarding the auditing charge, NAMB spokesman Mike Ebert countered by saying, “Our board of trustees, whose new members are approved each year by SBC messengers, provides overall oversight and accountability. The trustees have approved and regularly review a number of financial policies which ensure proper management of NAMB resources and which provide opportunities for any NAMB team member to report mismanagement to the board of trustees.

“We conduct an annual internal audit and an independent external audit. We report annually to the SBC Executive Committee and answer questions from (its) members. We report to messengers at the SBC annual meeting each year.”

But what state leaders want now is a forensic audit, not the standard audit most agencies undergo each year.

A second website, ReformNambNow.org, lays out additional financial questions being sought. It documents how NAMB’s reserves have increased 415% while evangelism funding is down 65%, church plants are down 50%, and baptisms are down 30%.

When it comes to reserves, Ebert said comparisons between NAMB and other SBC entities aren’t accurate because NAMB’s situation is so unique. NAMB’s reserves are at work, he said; they are active, serving church planters and other missionaries.

Seventy-five percent of the agency’s reserves are committed to church loans and property, he said. This property includes transitional missionary housing, buildings being used by church planters, and ministry centers.

NAMB also makes loans so that church plants, which otherwise would not qualify for conventional loans, can have places to worship, he said. When a church becomes financially stable, it usually refinances through another entity. The remaining 25% of its reserves are committed to contingency in case of a financial crisis and to short-term strategic projects, Ebert said.

At their early February meeting in New Orleans, trustees received an independent auditor’s report for fiscal year 2019-2020. According to a NAMB news release, “auditors gave NAMB an unqualified, clean audit, the highest rating possible.”

Critics, including the non-South executive directors, say that is not sufficient and they still desire a forensic audit.

To show the seriousness of this issue, in late December, 16 out of 24 California associational directors of missions put their names on the line and petitioned the state convention “to ensure California churches that Cooperative Program and other funds destined for the North American Mission Board will be used to advance transparent and cooperative mission work among all state conventions and associations.”

That letter further affirmed that the associational directors support the request “currently before the SBC Executive Committee to commission and direct an independent forensic financial audit of NAMB and report the complete findings of the audit to the entire Southern Baptist family of cooperating churches and partners.”

“This will allow all those who are contributing to the Cooperative Program to know how their sacrificial missions’ offerings are being spent,” the letter stated.

Loss of autonomy

Regardless of the outcome of a forensic audit, Agee says California Baptists will continue reaching the state with the good news of the gospel. “We are not going to settle for NAMB dictating California’s church planting policy and will not abdicate our responsibility.”

Because the future is cloudy, for the time being the state will continue to send 35% of its undesignated receipts, about $2 million, to the SBC Executive Committee and 3% to local California partners each year, Agee said. But the state missions offering — which now funds work previously jointly supported with NAMB — will continue to be highly emphasized.

The sentiment is the same and growing nearly 3,000 miles away on the Eastern Seaboard. The Baptist Convention of New England ministers to 16 million residents — of whom 94% are considered to be unchurched — and serves as a primary example of the talk of going it alone.

Terry Dorsett

Terry Dorsett serves as executive director for missions work in the six states of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut, Maine, and Massachusetts. The Great Commission Task Force’s decision to empower NAMB to cut its funding of all state and regional conventions, annex missionaries of their choosing and reassign them as church planters, affected their convention significantly.

Although he is a strong proponent of church planting, Dorsett and the churches feel ministry should be more holistic than just church planting.

Following the steady loss of NAMB funding and to maintain all the ministries needed to reach his region, Dorsett got creative. He began a fundraising campaign to replace ministries NAMB eliminated such as leadership development, youth ministry, collegiate ministry and ethnic church leadership development — an area that comprises 40% of the convention’s congregations.

That fundraising approach returns state conventions to a time six decades earlier when states and the SBC Home Mission Board operated separate and frequently with competing church planting tracts — a time before the Cooperative Agreements were created to combine resources and save money.

As a result of NAMB’s new policy, nearly 15 missionary and director of missions positions in New England were eliminated and converted to church planter catalysts. Today, with just 10% of the NAMB support they once had, the convention itself supports five full time and 12 part time missionaries. In addition, 25 collegiate missionaries now raise their own support.

Dorsett joined the SBC because he believes in cooperation, he said. He wants to work with NAMB, but his pastors often remind him that “NAMB used to fund directors of missions; now they don’t. They used to fund summer missionaries; now they don’t. They used to fund several staff members in the convention office; now they don’t. They used to fund collegiate ministry; now they don’t.”

NAMB, they tell him, “only plants churches.”

NAMB, they tell him, “only plants churches.”

This past year was especially difficult, but Dorsett was able to start a partnership with the South Carolina Baptist Convention that provided $100,000; individual churches in Alabama contributed $75,000; and there were gifts from individual donors. An aggressive state missions campaign jumped giving from about $15,000 to $75,000 in one year — once again largely through individual donors who were challenged to catch the vision of the New England convention’s outreach.

But what appears to be a success story has far more grave undertones.

“People in New England value the work of the convention and want to be a part of what we are doing,” Dorsett said of the campaign. But he cautioned, “you can only go to the well so many times before it runs dry.”

Task force suggested state-to-state partnerships

The kind of state-to-state partnerships the New England Convention is fostering were envisioned by the Great Commission Task Force Report as a way to offset the anticipated losses in funding created by the new model. The idea was to encourage partnerships between stronger and weaker conventions. But state executives like Dorsett said that concept, while admirable, is not a viable solution for sustained funding.

Title slide to one of NAMB’s online training modules for church planters.

In a March 2010 story in Baptist Press, Great Commission Task Force member Al Mohler explained the task force’ vision for state-to-state partnerships: “We want healthy state conventions in the old-line Southern Baptist states to be far more involved in helping younger developing state conventions, and we would rather the state conventions do that than NAMB. In other words, we would actually prefer that NAMB spend the majority of its time and energy not on developing pioneer state conventions, which we think the other state conventions can do far better.”

While similar partnerships have existed for years — alongside the Cooperative Agreement funding pattern — state-to-state partnerships never have been a cash cow for struggling weaker conventions. More than anything, the partnerships have promoted sending volunteers for mission projects.

The task force’s vision also didn’t take into account the economic downturns that would eventually cripple Southern states and their ability to administer partnerships.

“A partnership with another state convention is great for specific projects but is never a long-term commitment,” Dorsett said. “Conventions in the South are having their own struggles with declining Cooperative Program giving; individuals who supported us generously this year may not have the assets to do it next year.

“I’m not shy about asking for money,” he added, while acknowledging that being a fundraiser takes him away from other pressing responsibilities. And that is why his predecessors in the 1950s welcomed the advent of the Cooperative Agreements, he believes.

Meanwhile, state conventions now find themselves depending even more on a game of musical chairs as they seek what support they can from multiple other state conventions. For example:

- Montana has partnered with Missouri, Florida, Mississippi and Tennessee and the Southern Baptists of Texas Convention.

- Ohio has partnerships with Tennessee and New England.

- Alaska has an “unofficial” partnership with Alabama.

- Utah-Idaho partners with Georgia, Oklahoma, Southern Baptists of Texas, Kentucky and North Carolina.

- The Northwest Convention of Washington, Oregon and Northern Idaho partners with the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

Lean times in Southern states too

There is another wrinkle in the task force formula: Old-line states were led to believe that by relinquishing their Cooperative Agreements, their lost missions funds would be shifted to support the weaker conventions. But in reality, those funds have not benefitted states directly since the new funding bypasses the state conventions.

In 2009, when then-SBC President Johnny Hunt called for formation of the task force, the Cooperative Program reported a record $548 million; just two years later in the throes of the Great Recession, that income plummeted by $60 million to $488 million and never has recovered. Another $20 million was lost in undesignated giving in the following years, bringing the current loss against the previous high to $80 million.

Although local giving to churches has grown, those churches now send less money to their state conventions, which have had to tighten their belts while still sending a larger percentage of receipts — sometimes an increased percentage — to the SBC for its agencies and institutions. Absorbing that state-level loss on top of losing the Cooperative Agreements funding was a double blow.

Old-line states like Georgia were especially hard hit. Since posting a record $52.3 million budget in 2007, the state has trimmed $14.5 million from its budget. This year’s 2021 budget was reduced again to $37.83 million — down 6% or nearly $2.5 million from the previous year alone and down $14.47 million from the high 14 years ago.

Loss of directors of missions another blow

Another concern of the non-South conventions is NAMB’s unilateral decision to eliminate the positions of directors of missions, also known as associational missionaries.

The Baptist association is the historical bedrock of the denomination, founded to link churches together in ministry before there were state conventions. The Philadelphia Baptist Association was founded in 1707 — 138 years before the SBC itself — and was the template for today’s mission work.

The role of directors of missions came to an end when NAMB cut funding and converted many of them into church planters.

The role of directors of missions came to an end when NAMB cut funding and converted many of them into church planters. While stronger conventions could absorb the cost and keep their personnel by cutting other areas, the non-South conventions had no such ability.

The West — where there’s often a hundred miles or more between preaching points — has been particularly hard hit by the loss of directors of missions. Whether it be the Pacific Northwest, the Upper Midwest, or the Southwest, ministry is far more difficult than many in the Old South states can imagine. Distances are greater, isolation is common, and depression among pastors seeing little in the harvest weighs heavily.

Take Montana, known as Big Sky Country.

Barrett Duke

State executive Barrett Duke easily recites a variety of problems created by NAMB’s decision to no longer jointly fund missions personnel. The elimination of directors of missions has been far more devastating than in the South with churches aplenty and numerous opportunities for pastoral fellowship and brainstorming.

For many pastors in his region, the director of missions was the only listening ear for hundreds of miles.

“Our pastors no longer have the spiritual and emotional support once afforded by the directors of missions,” he said. “Being the fourth largest state (geographically) in the Union, it is not possible for me and one other full-time staff member to maintain those relationships.

“Our churches have become more susceptible to non-SBC pastors who befriend them and take them out of the convention. Too often the churches call non-SBC-affiliated pastors who lead them away or weaken their ties to the denomination.”

And just as important, he added, “Sometimes our pastors or their families go through significant turmoil before we hear about it and can come alongside to help. People in the South do not understand the amount of loneliness and isolation our pastors encounter.”

Duke sees that as opening a large back door that fuels some of the downward statistics as Southern Baptist churches cease to exist or leave the denomination.

“A number of churches have left our convention in the last few years because of the problems they are hearing in the denomination,” he said. “By the time we know about their struggle and help them work through it, it is often too late. These churches have represented years of hard work and significant expense. It takes years to recover from such losses.

“In my humble opinion, if things don’t change, when historians write about the decline of the Southern Baptist Convention, I believe they will identify the loss of the associational level of structure in the denomination as a major contributing factor. It might even be the single most significant factor to that decline.”

Duke said he understands the dilemma NAMB faced but thinks damage has been done in ways Atlanta leaders did not comprehend. “There is only so much money, and a lot of NAMB money was going to things that were not helping them accomplish their mission,” he said. “But the loss of so many support positions has severely affected our ability to help our churches get to the point where they are ready and healthy enough to do the work of evangelism and to start new churches.”

Randy Adams, speaking from his perspective in the Pacific Northwest, agrees.

“We are losing very important relationships with many of our pastors in the non-South conventions due to the loss of staffing. This is not the South where pastors get together for coffee or lunch … the distances are too great, and the isolation can be hard to deal with.

“For many years, our pastors knew someone representing Southern Baptists in their vast geographical area with whom they had a personal relationship. It might have been a director of missions or someone in the state office in whom they could confide.

“We are now entering a very serious breakdown in communications through the elimination of key positions on the field.”

“But we are now entering a very serious breakdown in communications through the elimination of key positions on the field. Southern Baptists have always been a relational people; we thrive on friendships and support. Those networks are now being dismantled far from denominational headquarters in Nashville, and it’s a problem from which we may never recover.”

Loyalty to whom?

Executives in both non-South and old South states have voiced concerns for years about creating a church planting network that makes end runs around their mission statements to reach their states for the kingdom of God. One of those concerns is NAMB’s creation of a network of “ambassadors” — usually pastors on a contract basis — which, intentionally or not, results in an erosion of the state’s presence among other pastors and church planters.

While on the surface an understandable idea, the net effect is to reinforce loyalty to an entity hundreds of miles away rather supporting the work of the local association or state convention, state executives say.

Adams, in the Northwest, reports that in February 2020, NAMB’ Ezell said 12 of the non-South conventions shouldn’t even exist. On another occasion he suggested they should be collapsed into one large Western convention based out of Denver.

The problem with that, Adams maintains, is that either that staff would have to be enlarged (replacing staff already in place but eliminated in the former conventions) or there would be even greater isolation for the church planters and pastors.

Either way, the close-knit network on which the West is being served would be crippled. A larger convention would not reduce the isolation but actually increase it, he says.

NAMB gift cards

Another sign of attempts to shift loyalty to the national body and away from state conventions, the state executives charge, is how NAMB uses its vast resources — partially accumulated by the $51 million it received with the elimination of the Cooperative Agreements — to send gift cards, sometimes worth hundreds of dollars, to church planters on wedding anniversaries, birthdays, Valentine’s Day for dates with a spouse, or during the holidays.

Depending on the occasion, the cards — and sometimes checks — range from less than $100 to more than $1,000. While state executives say they understand the goodwill these gifts endear, they complain the gifts create even more loyalty to NAMB while eroding the relationship with the state conventions.

A NAMB spokesman acknowledged the use of gift cards to build the spirits of church planters and their families with limited resources but declined to specify the value range of the items.

Joseph Bunce

Joseph Bunce, who retired Feb. 1 after 15 years with the Baptist Convention of New Mexico, says NAMB overstepped its boundaries by sending gift cards to his own convention employees without his knowledge. And that included staff members who had little, if any, professional contact with NAMB.

“I was not upset with anyone who received an unsolicited gift card. But it was like someone sending flowers to a neighbor’s wife because the neighbor was doing such a good job of mowing his lawn,” Bunce said. “It is a sly way to buy influence.”

Adams reports that as recently as December at least one staff member in the Northwest received two gift cards from NAMB totaling $450. The employee was instructed that the $300 should be given to his wife as a gift, and the $150 card was to be used to pay for a “date night.”

He does not know if others received such unsolicited Christmas presents.

Both state leaders maintain that NAMB is buying influence with its money — money that originates in churches and is passed on through their own state conventions. In other words, the very offerings they send to the SBC and NAMB are being used to create an unfair advantage against them.

Lack of transparency

Back in New Mexico, Bunce is troubled because in the last decade under the Great Commission Task Force plan, his state lost $1 million in SBC funding — and equally important the accompanying partnership — that provided for 26 jointly funded missionaries. Those individuals were part of a diverse force serving Native Americans, Hispanics, the deaf and multiple other unchurched groups.

Chart published by Baptist New Mexican showing declining NAMB partnership funding through the Baptist Convention of New Mexico.

“The root of the problem is until the day I retired I didn’t know how many NAMB personnel were in New Mexico or even where they were serving,” Bunce said.

For Bunce and other state convention leaders, this is like driving a car in the dark with no headlights.

Bunce is not alone when observing that NAMB was not historically created to bypass the states in local ministry; that was the assignment from the Great Commission Task Force. In NAMB’s earlier iteration, he said, state autonomy always was respected in a mutually beneficial relationship. The task force turned that on its head by creating a top-down entity with its national franchise approach.

“State conventions were never designed to be a franchise of a national entity,” he said. “In New Mexico, we want partnership, not to be franchised by a national entity. We want sole ownership of how we reach our neighbors with the gospel because we know better than anyone else.

“If you buy into the NAMB franchise network they, rather than the state convention, drive church planting. We are not interested in that corporate approach. In New Mexico, we have our own model for church planting that is driven by the local church. We do not tell the church what they are going to do or how to do it; instead, we ask the church how we can help resource them in their ministry. They, not the convention, are in the driver’s seat.

“That is how we define partnership.”

Where’s the bang for the buck?

State leaders agree that the loss of cooperation being extracted by the Great Commission Task Force directives is creating a breach in the denomination when it least can afford it. A national, top-down management approach to missions as envisioned by the task force is not how Baptists exploded outside their Southern borders and became the nation’s largest non-Protestant denomination.

They cite statistics saying NAMB is failing in its church planting goals even though it has more money — at their own expense — than at any time in history. Only a forensic audit can explain why and restore that trust, they argue.

They contend that regardless of how you parse the numbers, NAMB continues to plant fewer churches while its resources have increased from $23 million to $75 million annually as reported in the SBC Annual.

NAMB headquarters in Alpharetta, Ga.

And most importantly, after a decade of their latest restructuring, Southern Baptists continue to dwindle in membership. State leaders believe SBC messengers did not intend to gamble on the latest restructuring creating a super agency which, by their own design, would undermine 175 years of cooperation.

Shortly before its June 2020 annual meeting, the denomination announced its membership had dropped once again, this time by 2% year-over-year, the greatest in a century. The loss of 288,000 church members brings total SBC membership to 14.5 million, down from its peak of 16.3 million in 2006.

Meanwhile, as state convention executives convened their annual meeting this month, the president of the SBC Executive Committee published an appeal in Baptist Press for more cooperation.

“We are part of a convention that cherishes sending and supporting missionaries, evangelism, planting new gospel churches, providing theological education to prepare those called to ministry and demonstrating compassion for those who need relief in times of disaster and great need,” wrote Ronnie Floyd. “This is why the Cooperative Program’s early adopters believed this strategy could become the best way to fund Southern Baptists’ work across America and the world.

“Since its beginning in 1925, there have been many moments in Baptist life when cooperation became challenging. I believe we are in one of the most threatening moments related to our cooperation yet. This is why we need to come back home to Great Commission cooperation.”

When NAMB trustees met in New Orleans the first week of February, they “unanimously approved a resolution on cooperation and ministry strategy which stated support for NAMB’s strategic direction and the desire to work in cooperation with Southern Baptist partners,” a news release said.

NAMB’s current goals call for 5,000 new congregations in the SBC by the end of 2025, including 600 new church plants annually, 200 replants, 100 new campuses and 350 new affiliations.

And in his report to trustees, Ezell outlined NAMB’s current goals that call for 5,000 new congregations in the SBC by the end of 2025, including 600 new church plants annually, 200 replants, 100 new campuses and 350 new affiliations.

Yet state convention executives repeatedly express frustration that they can’t get numbers from NAMB. They don’t even know how many missionaries or church planters NAMB is supporting in their own states.

NAMB declined a BNG request for the state-by-state breakdown of church planters, a policy which its predecessor Home Mission Board published yearly along with all information about missions personnel. The number never has been released since the Task Force restructuring a decade ago.

Asked for clarification by BNG, Ebert, executive director for public relations at NAMB, explained that “most of our missionaries are church planting missionaries. Our funding runs for up to four (and in some cases five) years. A few exceptions go longer. Each year a group rolls off and a new group rolls on, so there is constant change and fluctuation.”

However, there are “some missionaries serving in long-term roles,” he added.

In sum for long-term workers, he reported current support for 177 church planters. That number includes 76 “church planting catalysts who work throughout North America helping to catalyze the start of new churches, working with current plants and working with partner churches”; 28 “city missionaries who help care for the plants and planters in that city, help recruit new planters and help recruit new partner churches to come alongside the plants”; 18 “SEND Relief missionaries”; and 55 “additional missionaries serving in various roles who are not directly planting churches.”

The total number of “missionaries” — an all-encompassing term at NAMB that includes long-term staff and short-term church planters — is 2,218 this year, down from 3,057 the year before, Ebert said.

The total number of “missionaries” — an all-encompassing term at NAMB that includes long-term staff and short-term church planters — is 2,218 this year, down from 3,057 the year before, Ebert said.

That drop was due primarily to “fewer church planting missionaries onboarded” because of a hold placed on new church launches, he explained, as well as suspension of student missionary options for the year.

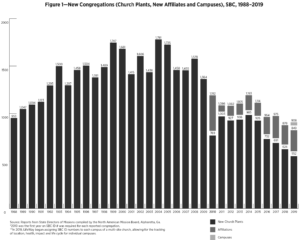

Regarding the number of new-church starts affiliated with the SBC, a multi-year chart created by NAMB and published in the 2020 SBC annual meeting Book of Reports shows total church plants in 2019 at one-third of the level reported prior to the Great Commission Task Force changes. In 2008, the SBC recorded 1,578 church plants, compared to 552 in 2019. However since 2010, the denomination has changed its reporting methodology to distinguish between church plants, church affiliations and added campuses.

When all three of those new categories are combined, the total for 2019 was 908, a 42% decrease from the 2008 high of 1,578 — and 300 less than the 1,250 combined annual church plants, campuses and affiliations Ezell has projected as necessary to reach the agency’s goals.

Joe Westbury is a veteran Baptist journalist who previously worked for the SBC Brotherhood Commission and Home Mission Board and ultimately retired from the managing editor position at the Georgia Christian Index. He lives in Atlanta.