A months-long battle for ultimate control of the Southern Baptist Convention’s agencies and institutions came to light Feb. 21 when a trove of attorney communications exposed a rift between officers of the SBC Executive Committee and leaders of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

The presenting issue is whether the seminary’s trustee officers have the right to suspend individual trustees accused of misconduct or whether that right belongs only to the SBC, which elects the trustees. In this case, two trustees were implicated in a financial scandal that caused the seminary to be deprived of money from a charitable foundation.

The deeper issue, however, is the meaning of a two-word phrase the SBC previously required all its agencies and seminaries to insert into their governing documents: “sole member.”

Beginning in 1997, the SBC Executive Committee asked the convention’s 12 agencies and institutions to make the SBC the “sole member” — or single controlling entity — of their corporations.

Beginning in 1997, the SBC Executive Committee asked the convention’s 12 agencies and institutions to make the SBC the “sole member” of their corporations.

This occurred in response to universities and other institutions that broke ties with state Baptist conventions as fundamentalists swept control of the SBC and most state conventions in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

For example, five agencies of the Missouri Baptist Convention declared their boards to be self-perpetuating after fundamentalists gained control of that state convention. In Texas, both Baylor and Houston Baptist University changed their charters so that their boards, and not the Baptist General Convention of Texas, elect a majority of their trustees.

As they gained all the levers of power within the national denomination, the new conservative leadership didn’t want the same thing happening there.

“The issue is one of ownership,” explained Morris Chapman, then president of the Executive Committee, in 2005. “Do you or do you not believe the SBC should own the entities that receive Cooperative Program funds?”

Chapman’s explanation was given as New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary became the last of the 12 entities to make the change to its governing documents, a change made under protest by then-President Chuck Kelley. New Orleans Seminary held out five years longer than any other SBC entity.

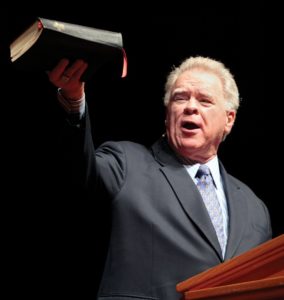

Kelley warned this was a “step toward centralization of control and authority.”

Chuck Kelley

Kelley warned this was a “step toward centralization of control and authority” exerted by the Executive Committee over all elements of the SBC. “Southern Baptists always have resisted centralization,” he explained. “Baptist polity emphasizes influence through trustees” rather than through centralized power such as the Executive Committee.

Ironically, it was actions set in motion by Kelley’s brother-in-law, Paige Patterson, that teed up the current dispute at Southwestern Seminary. Both Paige Patterson and his wife, Dorothy Patterson — Kelley’s sister — play a prominent role in the drama, even though Paige Patterson was removed as Southwestern’s president in 2018.

The Riley Foundation

Harold Riley was a prominent layman in Austin, Texas, and member of Hyde Park Baptist Church there. From humble roots in a South Central Oklahoma farming community, he went on to earn a business degree from Baylor University, became an All-American athlete, playing on the 1952 Orange Bowl team, and was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams. He declined that pro football career, however, to work in the insurance business.

Eventually he became president of National Western Life Insurance Company in Austin and then founded Insurance Company of America. In 1987, he became chairman of the board and CEO of Citizens, Inc., an insurance holding company.

With the wealth he accumulated, Riley became a major donor to both Southwestern Seminary and Baylor University. In 2002, he established the Harold E. Riley Foundation for the express purpose of supporting the two Texas schools.

With the wealth he accumulated, Riley became a major donor to both Southwestern Seminary and Baylor University. In 2002, he established the Harold E. Riley Foundation for the express purpose of supporting the two Texas schools.

He carried special affection for both schools — Baylor as an alumnus, and Southwestern because he had lived on campus there as a teenager when his father, Ray Riley, was a seminary student. Harold Riley gave millions to Southwestern, including the lead gift for a guest, conference and alumni center that later was named for his father and a $16 million lead gift for the seminary’s chapel and performing arts center.

When Harold Riley died in 2017, flags on the seminary’s Fort Worth campus were lowered to half-mast in his honor.

Fifteen years prior to his death, Riley established the foundation to perpetuate his generosity to Southwestern and Baylor. Each school was granted three members on the foundation’s board, giving the two schools a combined majority stake on the 11-member board.

Upon Riley’s death, assets of more than 1 million shares of Citizens Inc. were transferred to the foundation. According to the foundation’s 2018 tax documents, payouts to the two schools that year totaled $298,800 — less than the $348,816 reported in legal expenses that year. That also was the year the foundation’s assets mushroomed from $2 million to $15 million with an infusion of cash from Riley’s estate.

What went wrong?

In a meeting June 11, 2018 — nine months after Riley’s death — the foundation board was downsized and the schools’ right to appoint board members was eliminated. The foundation’s tax status was changed from a public charity to a private foundation.

In a meeting June 11, 2018 — nine months after Riley’s death — the foundation board was downsized and the schools’ right to appoint board members was eliminated.

Baylor and Southwestern sued, alleging that the meeting was conducted illegally, without adequate notice to Southwestern or Baylor and without the required number of foundation board members present. The lawsuit also asserted that in December 2017 —three months after Riley’s death — foundation trustees had “unanimously rejected” a member’s proposal to alter the governance rights in this manner.

The lawsuit further charged that after the board changes were made, “substantial assets and funds provided to the foundation by Mr. Riley have been irresponsibly wasted … and used for purposes other than to benefit Baylor and Southwestern.”

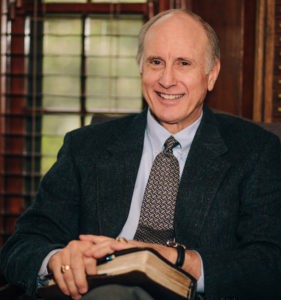

Paige Patterson

This important meeting of some of the members of the Riley Foundation board on June 11, 2018, occurred only days after Paige Patterson was fired by Southwestern’s board of trustees.

Mike Hughes, who served as the foundation’s president and a board member, was a Southwestern Seminary vice president under Patterson. The lawsuit argued that Patterson’s firing would have “rendered the termination of Hughes’ employment” at Southwestern “likely.”

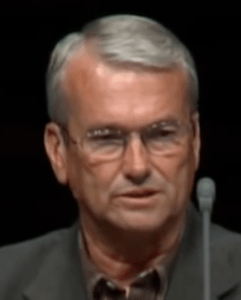

August Boto

The suit also asserted that two others among the rogue foundation trustees — August Boto and Charles Hott — are “longtime, close allies of Patterson in Baptist circles.”

The implication was that these three individuals not only sought to create personal gain through changes in management of the foundation but also sought to punish Southwestern’s trustees for firing Patterson.

Emails between Hughes and Boto discussed using Riley Foundation distributions to Southwestern and Baylor “as punishment for ‘every cock-eyed misstep,’ and as a method of keeping Baylor and Southwestern ‘lashed to the cross.’”

The lawsuit alleged that Riley Foundation board members “began paying themselves and set up employment and substantial pay for Hughes and Charles Hott.”

Ken Paxton

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton — himself the subject of ongoing litigation related to securities fraud — weighed in on the case, siding with the two schools and against the foundation.

Paxton alleged that Hott and Hughes hatched a plan “to ultimately convert the foundation into a stock trading platform.” Paxton further alleged that Hughes “knew he was going to be out of a job at Southwestern Seminary and put himself in position with the foundation to receive a six-figure paycheck, life insurance benefits, and unlimited use of a vehicle.”

Part of this plan allegedly involved getting Boto, Hott and Hughes seated on the board of directors of Citizens Inc., the $300 million publicly traded insurance company founded by Riley.

Part of this plan allegedly involved getting Boto, Hott and Hughes seated on the board of directors of Citizens Inc., the $300 million publicly traded insurance company founded by Riley.

The schools’ lawsuit said positions on the Citizens board of directors are compensated annually in excess of $100,000.

Mike Hughes

Further, this attempt to seat directors on the Citizens board initially included Patterson, according to legal filings, but Patterson withdrew last fall from the attempt to be seated as a Citizens director.

Serving on both boards

Hott, who served as chief investment officer for the foundation, also served as a trustee at Southwestern.

An attorney for the new administration at Southwestern said in now-public correspondence that Boto — a former general counsel and vice president of the SBC Executive Committee —“worked directly with Dr. Paige Patterson in 2017 to carry out a plan with the (SBC) Committee on Nominations to get Charles Hott on the Southwestern Seminary board of trustees” and that “within a month of his election to the seminary’s board, Dorothy Patterson recommended Mr. Hott to serve as a trustee for the Harold E. Riley Foundation.”

Charles Hott

Hott is a native Texan who previously has testified that he was “saved” from homosexuality — a spiritual life change he credits Paige Patterson as playing an instrumental role in bringing about when Patterson served on staff at First Baptist Church of Dallas. Hott was co-owner of a network of gay bars in Dallas, Houston, Arlington and El Paso, Texas.

Hott gave this testimony in a chapel address at Southwestern on Sept. 15, 2015.

The lawsuit brought by Southwestern and Baylor accused Hott of wrongdoing, along with Hughes, Boto and Thomas Pulley, another Southwestern trustee who is a former member of the Riley Foundation board.

As a result, seminary trustee officers suspended Hott and Pulley as trustees pending a full investigation.

This caught the attention of the SBC Executive Committee when, in October 2020, Hott and Pulley and another trustee, Randy Martin, reportedly were denied access to trustee meeting materials. Legal counsel for the Executive Committee wrote to Southwestern’s legal counsel to complain about this, asserting that “under Texas law a trustee has the right to participate in meetings of the board as long as he holds office.”

According to the attorney communications, Martin recused himself from the seminary trustee deliberations related to the Riley Foundation and Pulley was asked to do the same. Whether Pulley did or did not was not clear in the chain of emails and letters made public. Neither Pulley nor Martin were accused of wrongdoing in the litigation. Pulley’s connection appears to be based on his role as a former trustee of the Riley Foundation. Martin’s possible connection was not stated.

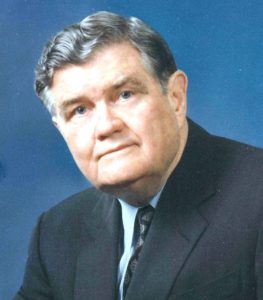

Ralph Pulley

In another twist of history, Pulley is the son of the late Ralph Pulley, who served a combined total of 22 years as a Southwestern trustee and was a leading critic of President Russell Dilday, who was fired by a new conservative majority on the seminary board in 1994 as part of the so-called “conservative resurgence” in the SBC.

Ralph Pulley was a deacon and lay leader at First Baptist Church in Dallas, where Patterson then was a young associate pastor and leader at the church-related Criswell Seminary. Although Patterson did not immediately succeed Dilday as Southwestern president, he is widely credited as being one of the primary leaders who made possible Dilday’s firing. Ralph Pulley for several years led that fight within the seminary trustee board, setting the stage for the school’s more conservative direction.

Tom Pulley is a Dallas-area banker who also is a deacon and lay leader at First Baptist Church of Dallas.

And in yet another historical irony, another current member of the Southwestern trustee board is Kie Bowman, senior pastor at Hyde Park Baptist Church in Austin, where Harold Riley was a member most of his adult life. Bowman has had no public role in the dispute between foundation leaders and the two schools.

Who controls the trustees?

Against all this backdrop, the larger question has been whether the seminary or only the SBC itself has the right to suspend, investigate or remove seminary trustees.

Southwestern’s administration, trustee officers and legal counsel believe the seminary board must be allowed to manage its own affairs or risk running afoul of both Texas law and accreditation standards. The SBC Executive Committee’s leaders, officers and legal counsel believe the “sole member” designation reserves that right only for the SBC, not for the board itself.

Southwestern claims even if the SBC has that right, it is a right that belongs only to the convention in annual session, not to the Executive Committee.

As a subpoint to this debate, Southwestern claims even if the SBC has that right, it is a right that belongs only to the convention in annual session, not to the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee claims it has full authority to act on behalf of the convention between annual meetings, including on issues of trustee removal or suspension.

In a Feb. 21 letter to the Executive Committee, seminary legal counsel Michael Anderson argued that the seminary’s own bylaws required trustee officers to take such action: “There is no question that the officers of Southwestern Seminary’s board had the right — if not the duty — to suspend Charles Hott and Thomas Pulley pending investigation.”

He added: “A basic principle of board governance is that a board must have the ability to address issues of misconduct in order to maintain the integrity of the board and protect the organization.”

Further, Anderson wrote: ‘No prohibition exists in any governing documents of either the convention or the seminary that prohibits the board officers of the seminary from investigating allegations of seminary trustee misconduct. To the contrary, the bylaws of the seminary specifically vest the duly elected officers of the board of trustees with broad authority to investigate a seminary trustee. Neither the Executive Committee, nor the SBC as sole member, has any authority over the bylaws of the seminary.”

Regarding the “sole member” legality, Anderson said: “When the entities amended their governing documents roughly 20 years ago to include the convention as the sole member of the entities, it was done so on a clear and repeated understanding that the convention — and the convention alone — can exercise the rights of sole membership.”

Earlier, on Oct. 16, Executive Committee attorneys James Guenther and James Jordan had written to strongly contest the assertion that seminary trustee officers had the right to deprive Hott and Pulley of full involvement as duly elected trustees.

“The SBC has the right to insist upon any trustee being allowed to serve in the office to which the convention appointed him.”

“It is our opinion that such difficulties cannot be solved by the officers of the board simply depriving a trustee of rights which the convention vested in him by appointing him as a trustee,” they wrote. “To do so would be tantamount to remove him from office, and neither the board nor its officers have authority to do that.”

This matters, the Executive Committee legal counsel said, because “if the board of any entity can exclude a convention-elected trustee from participating in the board’s meetings, then the right of the convention to determine the composition of the board is compromised. It is our opinion that the SBC has the right to insist upon any trustee being allowed to serve in the office to which the convention appointed him.”

And further: “Since the convention is not in session and only the Executive Committee can act for the convention ad interim, only the Executive Committee has standing to enforce the convention’s right for Mr. Hott to participate in the … meeting of the seminary’s board.”

Lawsuit settlement resolves the question for now

Just two weeks ago, on Feb. 8, the Baptist Standard reported that a settlement had been reached in the litigation between the two schools and the foundation board members.

That settlement returned control of the Riley Foundation to Baylor and Southwestern.

The Standard reported: “The settlement — reached after former Southwestern Seminary President Paige Patterson was subpoenaed but before he testified — required three foundation trustees to resign and bars them from employment and board service to any Texas charitable organization or Southern Baptist Convention entity.”

“The settlement … required three foundation trustees to resign and bars them from employment and board service to any Texas charitable organization.”

The settlement was entered Feb. 8 in the 67th Tarrant County Judicial District Court. It required that Hughes, Hott and Boto resign from the board and from paid positions of the foundation. The three also are prohibited from any efforts to discourage third parties from supporting the schools financially or to divert gifts elsewhere. And they are barred from accepting employment or appointment as an officer, director or trustee of any Texas public or private nonprofit charitable organization, as well as all SBC entities.

That means Hott no longer can serve as a Southwestern Seminary trustee. He has acknowledged his resignation. Pulley previously resigned from the seminary board, although when that happened was not stated, and he was not named in the legal settlement.

After the settlement, Southwestern Seminary issued a statement saying that Patterson had been subpoenaed “after evidence was presented showing involvement of Patterson, coupled with information provided to the Texas attorney general indicating efforts by Patterson and his associates to divert funds and redirect gifts away from the seminary to the Sandy Creek Foundation, his personal nonprofit organization.”

Baptist Press published a statement from Joe Cleveland, Hughes’ attorney, saying Hughes was “pleased that a settlement was reached … resulting in a complete dismissal of all claims against him without any admission of liability.”

Baptist Press also published a response from Boto: “The services rendered by the foundation’s trustees have always been in keeping with Harold Riley’s wishes, as well as in the best interests of both Southwestern Seminary and Baylor University. I trust the new trustees that the beneficiaries (they) have chosen will commit themselves to do those same things. I wish them well.”

In September 2020, Baptist Press reported Boto as saying the claims against him were “absurd” and Hott saying that “virtually every allegation” in the initial complaint was “completely false, without merit.”

What’s next?

The showdown between the seminary and the Executive Committee was a topic of conversation at the Executive Committee’s Feb. 22-23 meeting in Nashville.

Rob Showers (Baptist Press)

Rob Showers, chairman of the Executive Committee’s Committee on Missions and Ministry, announced he will appoint a task force to study the issue. Showers is an attorney from Ashburn, Va.

He told Baptist Press the task force’s focus will be to determine a “clear path” forward.

“Where there is trustee misconduct,” he said, “we need to figure out: How do we balance the sole membership interest of the SBC with the ability of entities to manage their own affairs and deal with that specific (issue of trustee) misconduct.

“The question comes when discipline doesn’t work and you’ve got a really bad actor and you can’t wait for the (SBC annual meeting). What do you do? And that’s really the question.”

Settling this question will have immediate implications far beyond Southwestern Seminary because the issue goes to the heart of just how powerful the SBC Executive Committee will be. Critics of the Executive Committee’s perceived consolidation of control in recent years see this as just one more overreach.

An SBC inside critic who tweets under the handle “Baptist Blogger” gave a running commentary on this week’s Executive Committee meeting. One of the posts referencing this issue said: “The Network Boy Empire just tried to strike back with a strong assist from Ronnie’s lawyers. But @AdamGreenway showed up. Guess that didn’t quite go as planned.”

“The Network Boy Empire” refers to the Conservative Baptist Network, a group within the SBC that seeks to drive the denomination further to the right. “Ronnie” is Ronnie Floyd, president of the Executive Committee. Adam Greenway is president at Southwestern.

The Conservative Baptist Network has called for a “second conservative resurgence” within the SBC to correct another perceived drift to liberalism. A group of Southern Baptist Calvinists called Founders Ministries also seeks to push the SBC more rightward.

J.D. Greear (Photo: Baptist Press)

In his address to the Executive Committee Feb. 22, SBC President J.D. Greear asked the governing board to “repudiate” a pharisaical spirit threatening the SBC.

“The last year has revealed areas of weakness in our beloved convention of churches,” he said. “Fissures and failures and fleshly idolatries. COVID didn’t produce these crises. It only exposed them.”

According to a Baptist Press report, Greear, senior pastor of The Summit Church in Raleigh-Durham, N.C., decried division, which he said comes from a small but vocal minority, because it hinders the SBC’s cooperative mission of getting the gospel to the nations. He described false accusations as “demonic.”

He specifically mentioned hot debate over the proper role of Critical Race Theory and discussions about systemic racism, a situation sparked in November 2020 by a definitive statement from the six SBC seminary presidents that sparked concern among Black SBC pastors.

The issue of centralized control within the SBC also is a current debate in relation to the convention’s North American Mission Board and state Baptist conventions, which claim NAMB and ultimately the SBC Executive Committee have wrested too much control from the autonomous state conventions.

Similar concerns lie at the heart of a current lawsuit brought by Will McRaney, who was fired as executive director of the Maryland-Delaware convention after alleged interference from SBC leadership.

And in yet another related matter, the Executive Committee this week received a highly contested report from another special study committee regarding leadership of the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. ERLC trustees and supporters claim the Executive Committee has overstepped its bounds by trying to overrule the guidance of the ERLC’s own trustee board.

Related articles:

Southern Baptist polity on trial in lawsuit appeal

What’s old is new again: Conservatives threaten funding over SBC’s ethics agency