Amid the recent tumult of events, the 100th birthday of George P. Shultz Dec. 13 passed relatively unnoticed. As did his death Feb. 6.

But attention must be paid.

Shultz was one of the ultimate “inside the Beltway” guys, those unelected government types people love to hate these days. So was another George who preceded Shultz as secretary of state: George C. Marshall. They, and a few others like them, didn’t do much except forge the modern world, win a world war, rebuild continents, defeat Soviet communism, prevent global chaos and nuclear destruction — little stuff like that.

George Marshall legacy

George Marshall

Marshall designed the European Recovery Plan, known as the Marshall Plan in honor of its architect. It helped feed, clothe and rebuild Europe while reconstructing its ravaged economies after World War II. No other single man — not Franklin Roosevelt, not Dwight Eisenhower, not Winston Churchill — did more to lead the Allies to victory in that conflict after a woefully unprepared beginning. Churchill himself said Marshall, as American military chief of staff and later general of the Army, was “the true organizer of victory.”

A supremely gifted technocrat, Marshall turned the United States from a mostly demobilized, isolationist bystander in the 1930s into a fearsome war machine that helped crush the Nazis and the Japanese. After the war, he served as secretary of state while the Marshall Plan unfolded, as secretary of defense after the Korean War broke out. He helped develop NATO, which defended Western European democracy. In 1953, Marshall received the Nobel Peace Prize — the only professional soldier so honored. He died in 1959.

George Schultz legacy

Shultz wasn’t quite as distinguished as Marshall, but in his quiet way, he came close.

A Princeton man (he had the school’s tiger mascot tattooed on one of his buttocks), Shultz served as a Marine Corps captain and artillery officer in World War II. After the war, he earned a Ph.D in economics at MIT, held various academic posts and rose through Republican ranks, eventually becoming Richard Nixon’s labor secretary, treasury secretary and director of management and budget.

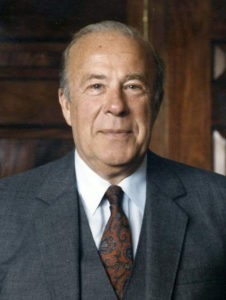

George Shultz

Boring, right? Except Shultz wasn’t done when Nixon fell. He managed to keep his reputation intact as the administration imploded during the Watergate scandal. There’s a reason for that: Shultz was a good soldier, up to a point. But he didn’t budge when asked to cross certain ethical lines.

According to journalist Lou Cannon, Shultz twice refused as treasury secretary to allow Nixon to use the IRS to audit political enemies or to stop an audit of Nixon’s own tax returns. “It was an improper use of the IRS, and I wouldn’t do it,” Shultz later said. At the time, Nixon furiously told an aide: “What does that candy ass think we sent him over there for?”

Later, as Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state for more than six years, Shultz served effectively while avoiding becoming entangled in the sordid Iran-Contra scandal, which nearly brought down that administration. He also refused to roll over when Reagan ordered lie-detector tests for government officials as a way to plug leaks.

“The minute in this government that I am not trusted is the day that I leave,” Shultz stated publicly. Reagan backed down.

“Trust is the coin of the realm,” Shultz often said. In an essay for Time Magazine as he approached his 100th birthday, he wrote: “‘In God we trust.’ Yes, and when we are at our best, we also trust in each other. Trust is fundamental, reciprocal and, ideally, pervasive. If it is present, anything is possible. If it is absent, nothing is possible. The best leaders trust their followers with the truth, and you know what happens as a result? Their followers trust them back. With that bond, they can do big, hard things together, changing the world for the better.”

“The best leaders trust their followers with the truth, and you know what happens as a result? Their followers trust them back.”

And Shultz did some big, hard things. As secretary of state, he negotiated the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with the Soviet Union, the only pact that actually reduced the nuclear arsenals of both superpowers. He guided Reagan, despite opposition from administration hawks, to forge a working relationship with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. That, in turn, laid the groundwork for the end of the Cold War — and of the Soviet empire itself.

I once saw Shultz in person. We both sat through the endless inauguration of some forgotten Central American president back in the 1980s — him motionless on the podium, me squirming in the audience while covering stories in the country. Secretaries of state do that a lot, and Shultz, with his Sphinx-like expression, was perfectly suited for it. Cool, calm, collected.

“If I could choose one American to whom I would entrust the nation’s fate in a crisis, it would be George Shultz,” wrote Henry Kissinger, one of his far more famous predecessors.

Where are the quiet giants today?

Why do I expend so many words on the two Georges, Marshall and Shultz? Because quiet giants like them no longer exist, either on the American scene or the world stage. America has stumbled through much of the post-Cold War era, unwisely led by presidents who shied away from global challenges (Clinton, Obama) or rashly overreached (George W. Bush).

And that was before Donald Trump steered the ship of state off the end of the earth.

The United States, once known for our moral leadership and stand for freedom and human rights in the world — despite our own glaring failures — became a near-pariah under Trump. He bullied and abandoned key allies and curried favor with dictators. He empowered dangerous populist demagogues in many countries. He imposed destructive trade tariffs on friend and foe alike. He pulled the United States out of important treaties and international organizations and questioned the existence of climate change and COVID-19.

“Prior to 2016, it would have been hard to imagine an American president rejecting American internationalism as thoroughly as Trump did.”

“Prior to 2016, it would have been hard to imagine an American president rejecting American internationalism as thoroughly as Trump did,” writes Hal Brands of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. “U.S. foreign policy has never been about altruism. But between World War II and the Trump presidency, every U.S. leader believed Washington could best advance its interests — whether securing prosperity or constraining authoritarians — by sustaining a liberal international order from which like-minded nations could benefit. The United States … would be a historically abnormal superpower, whose statecraft reflected its democratic values and a more inclusive notion of national good.”

Left- and right-wing critics of so-called U.S. imperialism may disagree, but American internationalism worked pretty well for 70 years at preventing another world war, spreading global economic prosperity and protecting and encouraging democracy.

Is the American era over? Many thought so even before Trump’s disastrous “America First” retreat. The age of superpowers is played out, they said. We need to clean up our own increasingly fractious house, they said. Let the world take care of itself; we’re not the global cop. Trump took that isolationist recipe and added a huge helping of populist nationalism, zero-sum economic self-interest, affection for strongmen and utter indifference to human need and human freedom.

Biden’s challenge

Can President Joe Biden turn the tide? Our closest allies no longer trust us, and Biden faces huge challenges at home that will demand much, perhaps most of his attention.

“Biden’s inclination — judging from his speeches, his track record in the Senate and as vice president, and his personnel choices — is to revive American internationalism and adapt it for an era of great-power rivalry,” Brands observes. “He will seek to repair alliances, reengage international institutions, and pursue broad cooperation on transnational issues while also sharpening the United States’ posture toward an increasingly belligerent China. Achieving all this won’t be easy.”

Talk about understatement. But Biden seems determined to try.

President Joe Biden addresses the Munich Security Conference.

“America’s back,” he said Feb. 19 in a video address to the Munich Security Conference, an annual gathering of top global security officials. He promised that the United States is “fully committed” to NATO and warned that democracy is “under assault” around the world and must be protected.

Biden already has directed that the United States rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement, the World Health Organization and other international groups. He has said America will once again welcome refugees and immigrants in search of political asylum. With a recommitment to internationalism, he could make a major impact on a whole range of issues: the global struggle against COVID-19; the battle against toxic nationalism; support for human rights and religious freedom; efforts to decrease global poverty; fighting climate change; and challenging China, Russia and other bad actors who have filled the vacuum left by Trump.

These issues call for moral leadership. They should concern us as Christians, if we care about the world beyond our borders. But reengaging them is also in our hard, cold national interest. If we ignore them, they will find us sooner or later.

“You may not be interested in war,” Leon Trotsky famously said. “But war is interested in you.”

Somewhere, the two Georges are watching.

Erich Bridges

Erich Bridges, a Baptist journalist for more than 40 years, retired in 2016 as global correspondent for the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Mission Board. He lives in Richmond, Va.