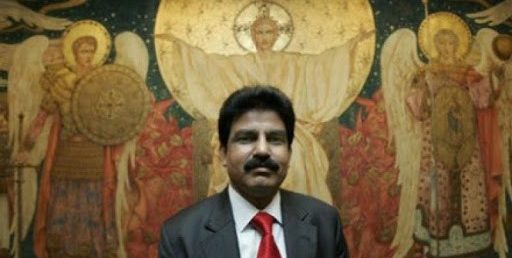

World religious leaders, policymakers and human rights activists gathered virtually March 2 to mark the 10-year anniversary of the assassination of Shahbaz Bhatti, the Pakistani Christian politician targeted by the Taliban for championing religious freedom. His killers never were prosecuted.

Bhatti’s brother and nephew, speaking from Canada, joined in the dialogue that included a panel discussion, more than 40 video testimonials and more than 50 written statements, including submissions from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and U.S. Sens. Mark Warner and Tim Kaine.

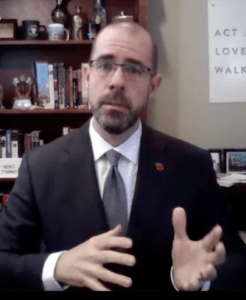

The faith-based courage Bhatti displayed in the face of relentless death threats ahead of his shooting helped inspire the massive turnout at his commemoration, said event co-organizer Knox Thames, a senior fellow at the Institute for Global Engagement and former special advisor for religious minorities in the Near East and South and Central Asia at the U.S. State Department.

Knox Thames

“It’s his heroic love of neighbor that makes him so inspiring. He is an example of it,” Thames said in a March 1 interview about his friendship with Bhatti. “He was a devout Catholic, but he was fighting to protect all Pakistanis who were being persecuted for their religious beliefs.”

Bhatti’s selfless dedication to religious freedom for all, Thames said, resonated with the principles of Thames’ own Baptist upbringing: “He was living out the call to ‘go and do likewise’ to reach across religious and ethnic boundaries.”

‘The martyrdom of Shahbaz Bhatti’

One of the most high-profile cases that demonstrated Bhatti’s compassion — and one that motivated his killers — was that of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman falsely accused and condemned under Pakistan’s notorious blasphemy law in 2010.

Bhatti, serving as minister of minority affairs under then-President Ali Zardari, took her case to the global community, including the United States, where Thames and others helped connect him with Congressional leaders, National Security Council officials and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Asia Bibi

Bhatti’s campaign for Bidi — and against the blasphemy laws that make Pakistan one of the most dangerous countries for Christians — also drew the attention of Muslim extremists who gunned him down in 2011 in Islamabad. World leaders, including U.S. President Barack Obama, issued statements lamenting Bhatti’s death.

Bidi was released in 2018 and immigrated to Canada. In her video tribute played during Bhatti’s 10-year commemoration, she recalled hearing the news of his death.

“I never can forget the martyrdom of Shahbaz Bhatti. To this day I continue grieving for him.”

She also pleaded for activists and politicians to keep the heat on Pakistan, where forced marriages, forced conversions and religiously motivated rapes are common. “The Christian community needs more heroes like Shahbaz Bhatti. Please help and support us.”

‘We had the rule of law’

How the international community can help was, in part, the topic of the virtual panel discussion. Participants also delved into Pakistan’s democratic origins and the magnitude of the challenge faced by potential reformers.

Peter Bhatti

“There was promise and hope” at the nation’s founding in 1847, panelist Peter Bhatti, the brother of Shahbaz Bhatti, said from Canada.

He cited a statement by the nation’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, promising freedom of religion: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed — that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

There were years when “everyone in Pakistan had equal rights,” he remembered. “We had the rule of law and lived in peace and harmony.”

But the forces of intolerance and extremism eventually ascended to power in both government and society, pushing religious minorities to the margins and resorting increasingly to violence to maintain control, he explained.

Bhatti said his brother was driven by a vision of Pakistan as a responsible member of the international community and as a place where interfaith dialogue and harmony could once again reign. But the march toward those goals has made no practical progress since the assassination.

A chilling effect on freedom

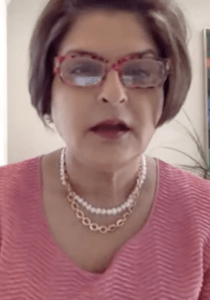

Panelist Farahnaz Ispahani, senior fellow at the Religious Freedom Institute and a former member of Parliament in Pakistan, noted that Bhatti’s killing has intimidated many who favor religious freedom in that nation, including Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and members of minority Muslim sects.

Farahnaz Isphahani

“Everyone got the message that … this is what is going to happen to you,” she said of Bhatti’s ambush killing.

Getting back to Pakistan’s founding vision of religious and cultural tolerance is a challenging task for the government, as well, she added. “The problem in Pakistan now is the politicians are too scared to talk about it.”

Ispahani added that the international community must therefore provide some of the pressure for change. “The problem of the blasphemy law, I think, is a global effort.”

That law is punishable by death and is among the harshest in the world as it is often used to settle scores not only with religious minorities, but also with Muslims, as well.

Pakistani society “has become more extreme,” she said. “We need a concerted interfaith effort and a global effort” to bring change.

Call for economic pressure

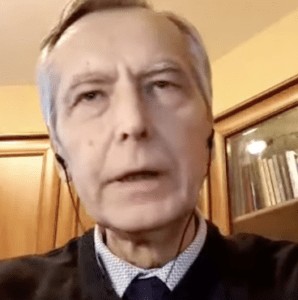

Panelist Jan Figel, former European Commission special envoy for the promotion of freedom of religion outside the EU, said that while Pakistan ranks “very high among intolerant societies,” economic leverage may be able to move the nation toward tolerance.

Jan Figel

The EU has entered a trade agreement with Pakistan that includes grading the nation on its human rights record. If they want the continued economic benefits, Figel said, “they must do more.”

Thames, however, cited Pakistan as one of the 10 worst countries for religious freedom and said it should face sanctions from the international community if it doesn’t make positive strides.

And reform is especially needed in education, he added, so that younger generations can learn the value of religious freedom and cultural tolerance. That’s a long-game approach that seeks to show young Pakistanis how to be around people who may not believe as they do.

“This has to be instilled in the young people of Pakistan or we will be dealing with these issues for decades to come,” Thames said.

Working for the global cause

Failure in Pakistan may have dire results beyond its borders, he added. “This is a disease that will spread and infect other countries in violent ways. This is not a future concern. This is a concern for today.”

Bhatti was aware of the global impact of his work for religious freedom in Pakistan, said panel moderator Rehman Chishti, a member of Parliament in the United Kingdom and senior fellow at the Religious Freedom Institute.

Rehman Chishti

“Shahbaz didn’t just do it for minorities in Pakistan, he did it for people around the world to be able to practice their faith freely,” Chishti said.

And he performed his work joyfully despite the threats, David Bhatti said in a video about his uncle, Shahbaz Bhatti, whom he described as capable of both radiating happiness and grieving the loss from suicide bombings and other acts of violence.

“He empathized with the grief of minorities” and was driven by faith to see that they never felt alone, he said.

David Bhatti

“Religious freedom is the most basic and sacred freedom to which all humans have a right,” David Bhatti said. “That understanding was rooted in his faith and enabled him to have the courage of his convictions until his very last breath.”

In a video recorded shortly before his assassination, Bhatti identified Taliban and al-Qaida forces that had threatened to kill him but said he would remain undeterred in his campaign for religious freedom.

“I want to share that I believe in Jesus Christ who has given his own life for us and I know the meaning of the Cross and I am following the Cross and I am ready to die for a cause,” he said. “These threats and these warnings cannot change my opinions and principles.”