There was a time, not all that long ago, when no minister, denominational leader or seminary administrator ever heard of — or worried about — a “none.”

That’s partly because there wasn’t yet a name for religiously unaffiliated Americans, partly because there were so few of them, and partly because they were limited to mostly younger, white liberals.

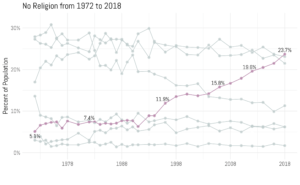

“They were 5% of the population in the 1970s and now they are around 30%. They are everybody now,” said Ryan Burge, a political scientist at Eastern Illinois University and author of the new book, The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going.

Ryan Burge

By “everybody,” Burge said he means every demographic. Research consistently shows that young and old, rich and poor, men and women and all races and political persuasions are reporting in as religiously unaffiliated. “You really can’t pin them down. Any stereotype you have in your head is wrong. It’s a much more diverse group now.”

Documenting the origin, identity and trajectory of what is now the largest and fastest-growing group in American religious life has become a significant part of not only Burge’s work but also the work of faith leaders concerned about what it all means for the survival of religious institutions.

The nones, and Burge’s analysis of them, also have drawn the attention of other researchers and authors including Carl Kell, a retired Western Kentucky University scholar who has penned multiple books about Southern Baptist Convention controversies.

Kell said he is leaning heavily on Burge’s illumination of religiously unaffiliated Americans for his next project, which has the working title of Requiem: In Remembrance of the Southern Baptist Convention.

The denomination’s own statistics testify to years of steady declines. Its single biggest decrease in 100 years occurred from 2018 to 2019, when membership fell by nearly 288,000 to 14.5 million, Lifeway Research reported. That represents a continual drop from 16.3 million in 2006.

The denomination’s own statistics testify to years of steady declines. Its single biggest decrease in 100 years occurred from 2018 to 2019, when membership fell by nearly 288,000 to 14.5 million, Lifeway Research reported. That represents a continual drop from 16.3 million in 2006.

Bible teacher and author Beth Moore’s high-visibility break with the SBC in March is another indicator of the convention’s downward trajectory, said Kell, a former Southern Baptist.

But Burge provides a wider context to the convention’s challenges, Kell added. “The point of all this is that we can see that American denominations are going to go into receivership. There is no doubt about it.”

That’s why Burge will contribute a chapter about the nones to Kell’s next book. “You can read polls (on the nones) until you are blue in the face, but they don’t provide interpretations of the data like Ryan does.”

Burge is active on Twitter and posts new data and interpretations every week. His Twitter description reads, “I make graphs about religion.”

Burge said his book was written to offer essential context to laypeople, clergy, denominational leaders, seminary teachers and journalists. “This is not a book for social scientists,” he explained.

Burge said his book was written to offer essential context to laypeople, clergy, denominational leaders, seminary teachers and journalists. “This is not a book for social scientists,” he explained.

Nor does the book offer techniques on getting religiously unaffiliated Americans into the pews.

“I don’t take a prescriptive approach,” he said. “This is not about how churches can win back the nones. I wrote it as a descriptive manual of what the nones look like — their gender and age, and race and education and all those things we wonder about.”

Another aim is to help pastors set aside any guilt they may feel about the rise of the nones.

“The nones were going to leave anyway. Secularization is a result of globalization and it’s futile to try to stop it,” said Burge, who is a pastor in the American Baptist Churches in the USA. “I see pastors getting bummed out when they see the stats, but nothing they did or did not do contributed to that. Secularism is not stopping. It’s only accelerating in America and across the world. The American religious landscape is always going to continue to be altered by secularism.”

It’s equally futile to try to pigeon-hole this group of Americans, he advised. “Today, they are more politically diverse and regionally diverse. It’s really hard to pin them down.”

Some of them are angry at or afraid of religions. For example, LGBTQ people often feel ostracized in religious settings, while others are turned off by politics in the pulpit. Still others are turned off by theology in general, and some just never went to church growing up.

“For every old religious person who dies, they are being replaced by a younger person with no religion.”

Generational differences are driving some of the numbers, Burge added. “For every old religious person who dies, they are being replaced by a younger person with no religion. So while 30% of the overall population are nones, among Gen Z it is 40%.”

And assuming nones are all atheists and agnostics also is counterproductive, he warned. Combined, atheists and agnostics comprise only 12% of the religiously unaffiliated while a subgroup known as “nothing in particular” makes up as much as 20% of nones.

Nones “are one of the largest religious groups in America today and are the same size as white Catholics and slightly smaller than evangelicals,” Burge emphasized.

Most remarkable is how quickly religiously unaffiliated Americans have ascended from obscurity in the 1970s to where they are now.

“One thing that fascinates me is how fast they’re growing,” he said. “It is just incomprehensible. Change is glacial for most religious groups, but the nones are growing a point or two every two years. You just don’t see that with other religious groups.”

Related articles:

Gen Z and growth of the ‘nones’ might have swung presidential election

Faith leaders see ‘nones’ coming to church for community, spiritual direction

Tell the Jesus story and stop worrying about numerical growth, historian advises