Don’t get me wrong. I’m keen on Nordic and UK mysteries. But last week, my friend and I sought relief from plotlines that feature a cranky, substance-abusing detective who alienates family and colleagues yet ensnares the killer.

These sagas sometimes occur in small towns that, in reality, have some of the lowest homicide rates in the world. We are more likely to have our bicycle or wallet stolen when we visit there. After overindulging in the early pandemic months, I’m on a media diet. If sitting is the new smoking, then I need to cut back a pack or two.

Paula Mangum Sheridan

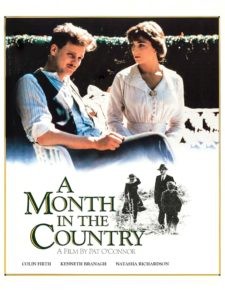

I’m glad I didn’t miss this gem. We discovered “A Month in the Country,” based on the 1980 novel by J.L. Carr. The fictional story’s narrator, Tom Birken, a World War I veteran, reflects on the summer he was hired to uncover a Medieval mural obscured by whitewash in a Yorkshire village church.

Birken suffers from terrors of the war in the trenches and the battle in his heart. His wife left him, yet again, for another. His trauma-fueled facial twitch and stutter cause others to avert their eyes. He nestles himself in the church belfry where he lives and works as the villagers trickle in to marvel at his labor.

Birken’s seasoned, patient hands reveal the Last Judgment scene of an anonymous artist. Birken’s gifts herald the talent of an unknown master who came before him. He is a servant to the painter, giving his all with delicacy and precision.

Birken knows that doing too much or too little will obliterate the beauty of the original images he longs to reveal. He is not there to touch up or fill in as the minister expects him to do. He wants to reveal, not embellish, the entirety of the artist’s work. In doing so, he discovers images of blissful eternal life and tortured damnation to the flames of hell. It is all there. It is a heaven and hell that Birken has experienced on earth.

The more Birken discovers parts of the masterpiece depicting the Final Judgment, the more he uncloaks the hidden but beautiful parts of himself. He allows children and neighbors to care for him and stands firm when the church’s minister attempts to shortchange. He navigates his work and community relationships, revealing his vulnerable authenticity as he reveals the fragile, hidden masterpiece. He learns that love and sorrow illuminate each other to create a picture as precious as the one he restores in the church.

The more Birken discovers parts of the masterpiece depicting the Final Judgment, the more he uncloaks the hidden but beautiful parts of himself. He allows children and neighbors to care for him and stands firm when the church’s minister attempts to shortchange. He navigates his work and community relationships, revealing his vulnerable authenticity as he reveals the fragile, hidden masterpiece. He learns that love and sorrow illuminate each other to create a picture as precious as the one he restores in the church.

This story told on the screen and the written page captivates my heart and mind. Tom Birken’s reflections teach me several life lessons.

It is sacred to magnify the gifts of others, making room for talents that are not our own. Perhaps we encourage expression, discover a gift unknown, or applaud as one hones a craft. We lift the talents of others, making them more visible. We are servants of their gifts, honoring and protecting another’s light.

We cultivate fertile ground for nurturing our gifts when our community honors inquiry, belonging, and possibility throughout our life span. We explore, attempt, and fail as a way of life, free from shame and blame.

We repair when things don’t work out the first time. We make space for others to do the same. We have the humble audacity to nourish and be nourished.

“The story reminds me that kindness and care can elude us where we expect them to be found.”

The story reminds me that kindness and care can elude us where we expect them to be found. The Anglican minister recites Jesus’ command to take in the stranger. Yet he denies lodging to Birken while living in a house of empty rooms. The Methodist minister/station agent preaches sin and damnation, but he and his family welcome Birken into their simple home, integrating him into their daily activities. We later learn that the Anglican minister feels useless in a community with a wavering interest in the sacred. He channels his sorrow through coldness and isolation. He suffers and causes suffering. Where does Birken feel healing and belonging? Where do we feel included? We quickly discern that loving actions restore us more than hollow words.

The story teaches me that happiness and sorrow are not always opposites. We can carry both in our souls in our life. We can grieve and seek peace at the same time. We can chuckle and still long for someone. I’ve heard some of the most heartfelt laughter at memorial services, where people tell their truths about the complicated loved one we’ve lost. We don’t have to be perfect to be lovable. We don’t have to pretend anyone else is perfect, either.

Our lives become more authentic when we allow sorrow to sit with us. Sorrow doesn’t have to drown us or numb our senses indefinitely. It can inform and enrich our capacity to love ourselves and be fully alive to live in a beautiful, messy and dangerous world.

“Our lives become more authentic when we allow sorrow to sit with us.”

Like Birkin, many heal when we have sacred rhythms of rest, meaningful work and people who lovingly bear witness to our pain. If we choose to talk, it is on our timeline. Words cannot always represent our inner experiences. If sorrow does overpower us, then we deserve support and care from people who can help. We also can be present for those who feel overwhelmed as they find their footing.

Perhaps we should revise our description of happily ever after. We pin pictures to our virtual Pinterest page of what our happy lives should contain. We may hope for a dream house, the ideal partner, the fulfilling job, the abundant bank account, or perfect children who grow up to cure cancer or COVID and create world peace.

While such desires appeal, more flexible, porous aspirations give us the freedom to imagine new possibilities. Sometimes our first wish list doesn’t come true. It may be in our best interest to lose some of our dreams. Sometimes we don’t know that new opportunities exist until we lose what we hold dear. Several roads lead us home.

We are the artists who lovingly restore the murals of our lives and our community. We also are God’s mural, created and restored with loving hands.

Paula Mangum Sheridan recently retired from Whittier College as an associate professor and program director of the social work department. She is a licensed clinical social worker and supports voter accessibility and the rights of people without homes in her community.