Dallas pastor Richie Butler has blazed a trail through the worlds of real estate and ministry in Texas and nationwide, developing more than $500 million in urban properties, leading iconic Black churches and launching initiatives to combat racism and deliver COVID-19 testing and vaccinations to communities of color.

And it all began with a challenge from a mentor while a student at Harvard Divinity School.

“In my first meeting with him, he gave me a blank piece of paper and said, ‘That is your ministry. Go make it happen.’ That has shaped me going forward,” said Butler, senior pastor at St. Luke Community United Methodist Church in Dallas and founder of Project Unity, a ministry dedicated to racial healing.

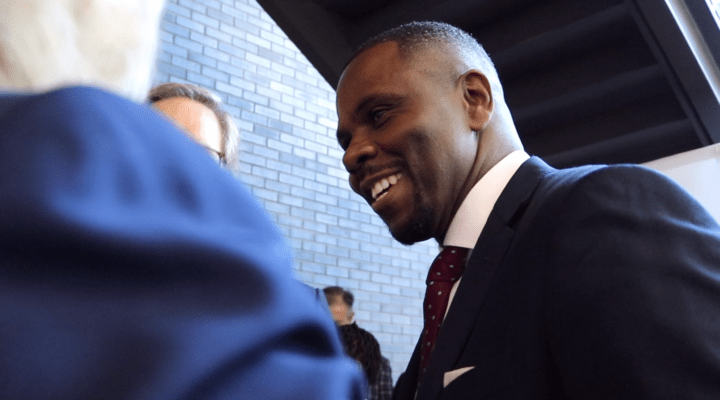

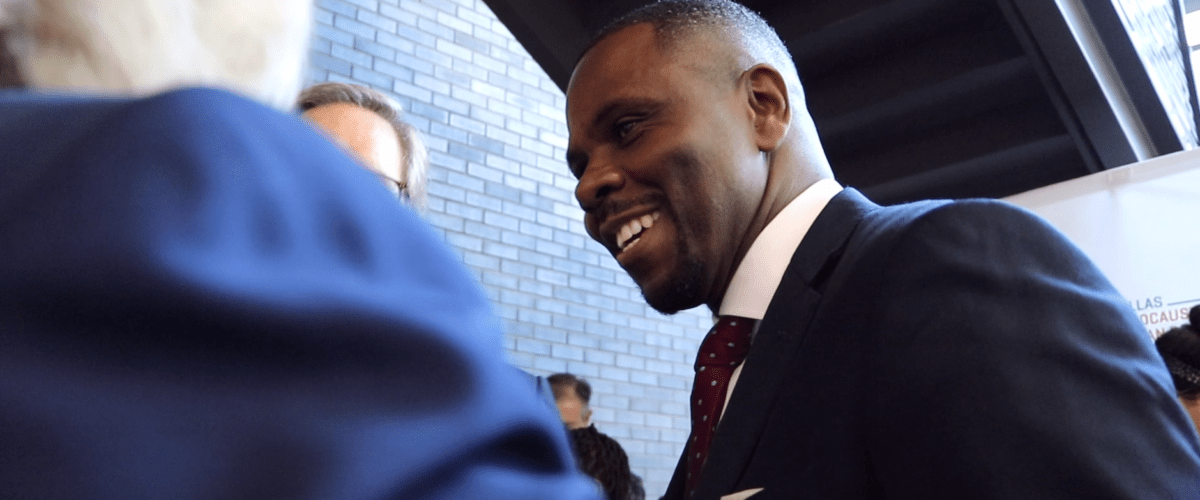

Richie Butler

Lately that healing has involved bringing COVID-19 testing and vaccinations to various locations around the city, including churches. “This is born out of the pandemic as we realized communities of color were disproportionately impacted,” he said.

The goal is to continue the operation with other health services going forward, Butler said. “We are trying to lean into using this pandemic to address wider health disparities. We hope this can be a new model for health care delivery.”

Butler has been just as ambitious in his finance, banking and real estate pursuits, which he said have emerged from his calling to ministry.

“I told God when he called me to preaching to please let me be in pulpits on Sundays and let me do deals on the weekdays. And I said I will dedicate it all to him.”

Butler grew up in economically challenged East Austin, Texas, and was determined early in his career to help revive impoverished neighborhoods.

“While I was at SMU (Southern Methodist University) I determined that real estate developers are people who can take a piece of dirt or a building and revitalize them,” he explained. So, I leaned into real estate as a way of building community the way church builds people.”

“I leaned into real estate as a way of building community the way church builds people.”

His first deal, in 1999, involved a coalition of pastors that created Unity Estates, a single-family home development for first-time buyers in Dallas. The goal was to help people of color build wealth in economically deprived areas.

In 1996, after seminary, there was a stint in Massachusetts as deputy political director for John Kerry’s U.S. Senate campaign.

“The work I have been doing is about building people and building communities; when communities or people are hurting, we need to address the hurt,” the pastor explained.

Butler has been equally entrepreneurial in his church life. Raised in Missionary Baptist churches, he eventually founded Union Cathedral, a non-denominational church in Dallas. In 2014 his congregation merged with St. Paul United Methodist Church, one of the oldest Black congregations in the city and one founded by slaves.

“St. Paul was a dying church. But the merger transformed that 141-year-old congregation, and it transformed the ministry we were doing in the community,” he said.

In 2020, Butler was assigned to St. Luke, a 4,000-member predominantly African American congregation. As before, his leadership provided a boost for the congregation and the church provided a boost for him.

“They needed a shot in the arm. We all did,” he said. “And so, I started in the middle of a pandemic and it’s been a good fit for me and has helped move ministry forward.”

But ministry for Butler exists both inside and outside the four walls. In 2014, he launched Project Unity in response to the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and subsequent months of protests that gripped the city and nation around issues of police militarism and violence.

The need for such an organization was immediately apparent, Butler said. “It was a month after we (St. Paul and Union Cathedral) merged when we hosted a town hall meeting at church in response to what was going on in Ferguson. We had the district attorney and the chief of police at the church. It was a full house and every negative emotion you don’t want was on display. It was anger, mistrust, fear, resentments. You name the negative emotion and that’s what was stirring in that space.”

That project also gave birth to Together We Test and Together We Vaccinate, the ongoing campaign to establish city-wide vaccination stations.

Project Unity then organized “a year of unity” after the 2016 massacre of five Dallas police officers killed by a lone gunman during a protest, Butler said.

The ministry operates a number of ongoing programs designed to promote anti-racism, all themed as “Together We…” efforts. Together We Sing presents concert series. Together We Pray, Read and Learn also are offered.

Together We Can was inspired by the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020. It includes Together We Dine, which brings white, Black and other people of color together for conversations about racism.

“Together We Can also offers a one-hour-per-month action item that offers a set of activities you can do in an hour, such as reading, listening. to a podcast, or a video,” Butler said. “It’s educational and promotes a lifestyle and mindfulness about being anti-racist.”

People wait in line to receive a COVID-19 vaccination at Methodist Hospital in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas, Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

That project also gave birth to Together We Test and Together We Vaccinate, the ongoing campaign to establish city-wide vaccination stations.

Butler said his sense of purpose has been affected by the work of his church and Project Unity.

“I have realized there is a resonating theme to my ministry and to my calling. It is the word ‘unity.’”

And the fact that there seems to be no end to social and racial injustice does not discourage him.

“There is always this Holy Spirit and God saying this is what you are called to do. I am an eternal optimist. The glass is always half full for me. I continue to see hope and possibility and progress.”

Related articles:

Religious communities can offer more to the coronavirus vaccination effort | Opinion by Michael Woolf

Public health officials find churches are ideal sites for COVID vaccine clinics

Interpreting the data: Why are some Christians getting vaccinated and others aren’t?