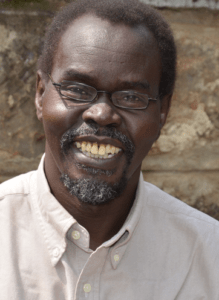

The look on his face at the hospital bed where he was undergoing treatment showed a man who was recovering, happy and grateful to God to be alive. It was the opposite situation on Sunday, April 25, when an encounter with gunmen who invaded his residence left him in pains.

On that day, Christian Carlassare, an Italian-born Catholic priest and bishop-elect of South Sudan’s Rumbek Diocese, was at home when the uninvited guests arrived in the darkest hour of the day and shot at his bedroom door with the intention of gaining entry. When the door got open, the bishop came out and asked what their mission was. They responded by shooting at his legs, leaving him writhing in pain.

In a bid to save his life, the bishop was flown to Kenya, where a picture of him in high spirits later emerged.

Christian Carlassare

In a video message reported by Vatican News, Bishop Carlassare thanked those who had prayed and stood by him through his ordeal.

“I acknowledge the solidarity, the powerful stand of my elder brothers of Sudan and South Sudan as they see this attack on one member as an attack of the whole church. I am grateful for the sincere commitment of the government of South Sudan — from the presidency to the authorities at the local level. (Also, for their desire) to uphold the truth, by taking legal action to correct the evil that has happened in Rumbek so that it may never happen again,” he said. “It is not the people of South Sudan who shot me; it is not the Dinkas who shot me, (not) the Agar (people). It is just a group of people who have no human values and who are a shame to their community.”

He called on members of the community to be vigilant and ensure that evil does not gain ground in their land.

“Do not allow violent members to hold the whole community hostage,” he advised.

Echo of an early murder

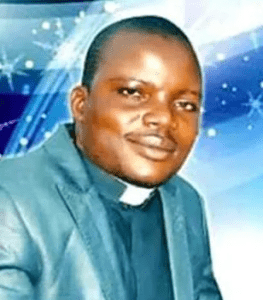

The shooting of Bishop Carlassare brings to mind the incident of Nov. 15, 2018, when Father Victor-Luke Ohdiambo, a Jesuit Priest, lost his life after some gunmen stormed the Jesuit community in Cueibet and opened fire on him.

Victor-Luke-Odhiambo

Following his death, the Society of Jesus, in a press statement, said that Odhiambo “worked in war-torn South Sudan for over 10 years … (and) at the time of (his) death … was the principal of Mazzolari Teachers’ College in Cueibet and acting superior of the community.” It further revealed that Jesuit members and their partners in mission had worked in different parts of South Sudan and had been attacked “multiple times, forced to abandon a school in Wau, ambushed by armed gangs, kidnapped, and witnessed violent attacks on innocent South Sudanese.”

South Sudan in 2018, unlike now, was embroiled in inter-ethnic conflict sparked by a power struggle between President Salva Kiir and his deputy, Riek Machar. The latest attack on Bishop Carlassare is just one example of the assault or danger many Christian clerics face, not just in South Sudan but in many other African countries in their work as ministers of the gospel.

Death across Africa

In neighboring Ethiopia, 24 people, two of whom were ministers, were murdered by armed militants in western Ethiopia in March this year. The victims were said to be attending a church service in Horo Guduru Welega when they were surrounded and attacked.

The assault was blamed on OLF Shenie, a radical group with ties to a separatist group, Oromo Liberation Front.

A similar tragedy played out in the Central African Republic in mid-November 2018 when two Christian leaders, Bishop Blaise Mada, vicar general of the diocese of Alindao, and Celestine Ngoumbango, parish priest of the village of Mingala, were found to be among the more than 40 persons who perished when persons suspected to be members of Unité pour la Paix en Centrafrique, a Muslim rebel group, attacked a cathedral in Alindao that served as sanctuary for people displaced by previous violence in a country plagued by Christian-Muslim conflict.

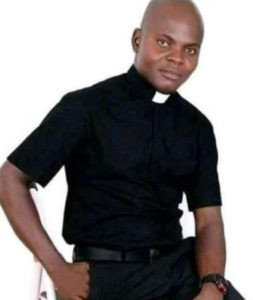

Ferdinand Fanen Ngugban

In Nigeria, cases of attacks against church leaders by armed men are not new. On March 30 this year, a Catholic priest in Katsina-Ala, Benue State, Father Ferdinand Fanen Ngugban, was shot and killed by unknown persons.

A day after the incident, the Catholic Diocese of Katsina-Ala released a statement showing the events that led to the death of Ngugban, who was ordained a priest on July 4, 2015, and served as assistant priest at St. Paul Parish.

“After celebrating Mass, and while he prepared to leave for Chrism Mass at St. Gerard Majeila Cathedral, Katsina-Ala, to renew his priestly vows alongside his brother priests, there was pandemonium among the internally displaced persons who took refuge in the parish premises,” the statement explained.

Ferdinand “went out to find out the cause of the confusion. He was shot in the head as he tried to take cover after sighting armed men.”

John Gbakaan

Two months before Ngugban’s death, the Christian community in Nigeria had been thrown into mourning when news emerged that John Gbakaan, parish priest of St. Anthony Church in Gulu, in the diocese of Minna, had been brutally murdered after being kidnapped with his brother. The kidnappers were said to have first demanded a ransom of 30 million naira (equivalent to $78,947 US), which they later reduced to 5 million naira ($13,158), in exchange for his life. The mutilated body of the priest was found close to where he was abducted, while the fate of his brother was unknown.

What wasn’t clear at the time of Gbakaan’s abduction and gruesome murder, was whether the kidnappers were bandits or terrorists from jihadist groups like Boko Haram or Islamic State in West Africa Province. Such jihadists have been fingered previously as masterminds of similar crimes mainly in the middle belt and northern regions of Nigeria.

In January 2020, Lawan Andimi, chairman of the Christian Association of Nigeria in Michika Local Government Area of Adamawa State, was kidnapped and then killed despite his Boko Haram captors being offered money for his release.

The terrorists demanded 2 million Euros as ransom, which was provided but they still beheaded him.

Bishop Dami Mamza, the state CAN chairman, while speaking to journalists in Yola, capital of Adamawa State, said the terrorists demanded 2 million Euros as ransom, which was provided but they still beheaded him. “Negotiations were still ongoing when they stopped calling.”

In the same January 2020, Denis Bagauri, a clergyman with Lutheran Church of Christ in Nigeria, was murdered by unknown gunmen who stormed his residence in Nassarawo Jereng, Mayo Belwa Local Government Area of Adamawa State.

In Burkina Faso, the body of a missing priest, Father Rodrigue Sanon, was discovered on Jan. 21 of this year in the forest of Toumousseni, about 20 kilometers from Banfora. Until his death, Sanon was the parish priest of Notre Dame de la Paix in Soubakanyedougou, southwest of Burkina Faso. He had been missing for two days before his body was found. News of his death was relayed by Lucas Kalfa Sanou, bishop of Banfora.

While the circumstances leading to Sanon’s death were unclear, it brought to mind the horror of May 2019, when a band of killers swooped on a church in Dablo, Burkina Faso, and snuffed the life out of Father Siméon Yampa and five other parishioners.

Before this incident, a Protestant pastor and five other faithfuls reportedly lost their lives in Soum province.

In two other unrelated incidents, a Spanish priest was one of five persons murdered in the Eastern part of Burkina Faso while Father Joël Yougbaré, parish priest of Djibo, disappeared without a trace.

Islamic fundamentalists blamed

Just like in Nigeria, many cases of abductions, killings or persecution of faith leaders in Burkina Faso are blamed on Islamic fundamentalists. Despite its secular nature, jihadist groups appear to be gaining ground in the French-speaking West African country.

Just like in Nigeria, many cases of abductions, killings or persecution of faith leaders in Burkina Faso are blamed on Islamic fundamentalists.

However, not everyone unlucky to have been kidnapped by criminal elements or extremist groups ends up losing their lives. On Christmas Eve last year, Boko Haram abducted Bulus Yakura, pastor at the Church of the Brethren in northeast Nigeria, but later released him after more than two months in captivity. Yakura’s release followed his passionate appeal on video to the Nigerian government and people to mobilize and help save him from imminent death. “Today is the last day I will have the opportunity to call on you in your capacity as my parents and relatives in the country. Anyone who has the intention should help and save me,” he begged.

Beyond church leaders, members of Christian congregations generally are targeted not just in countries like Central African Republic, Burkina Faso and Nigeria but places where religious differences are exploited by some for their selfish or evil agenda.

Muslim leaders also attacked

And it is not just Christian leaders who bear the brunt of religious extremism.

Muslim imams or scholars who do not share or approve of the extremist ideology of terrorists, as well as moderate Muslims are known to have been targeted for attack. One such Islamic preacher who paid the supreme price is Sheik Adam Albani, who was killed in Zaria, northern Nigeria, along with his wife and son, by suspected Boko Haram members. Albani was said to be a vocal critic of the terrorist group.

Muslim imams or scholars who do not share or approve of the extremist ideology of terrorists, as well as moderate Muslims are known to have been targeted for attack.

At times, unprovoked attacks by criminal elements or insurgents lead to reprisals, thus deepening suspicion and animosity among people of diverse faith. Over the years, many churches, priests and congregations, and mosques in particularly volatile areas of their countries, have adopted various security measures as a means to avert danger.

In the latest 2021 Open Doors World Watch list of top 50 countries with extreme levels or very high levels of religious persecution, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, CAR and Ethiopia are among the countries featured, with Nigeria placing ninth but topping the bill in Africa as a country where religious persecution is rife. North Korea is first on the list, followed by Afghanistan, Somalia, Libya, Pakistan, Eritrea, Yemen, Iran, among others.

Part of the key findings of the Open Doors research is that “Islamic militancy exploited COVID-19 restrictions to gain ground in sub-Saharan Africa. Militants increased violent attacks across the region, exploiting the inability or unwillingness of governments to protect vulnerable communities.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian native and freelance religion journalist who lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

21Wilberforce ranks members of 116th Congress on support for international religious freedom