The growing cultural and political gulf between Americans is not unique in the world today but appears to be more extreme than what is happening in several Western European nations, according to Pew Research Center.

Its new study, “Views About National Identity Becoming More Inclusive in U.S., Western Europe,” reveals that struggles with immigration, definitions of authentic national identity, and sticking to traditional customs versus allowing social innovation are not exclusively American conflicts. But the report does find the U.S. often corners the market on those divisions.

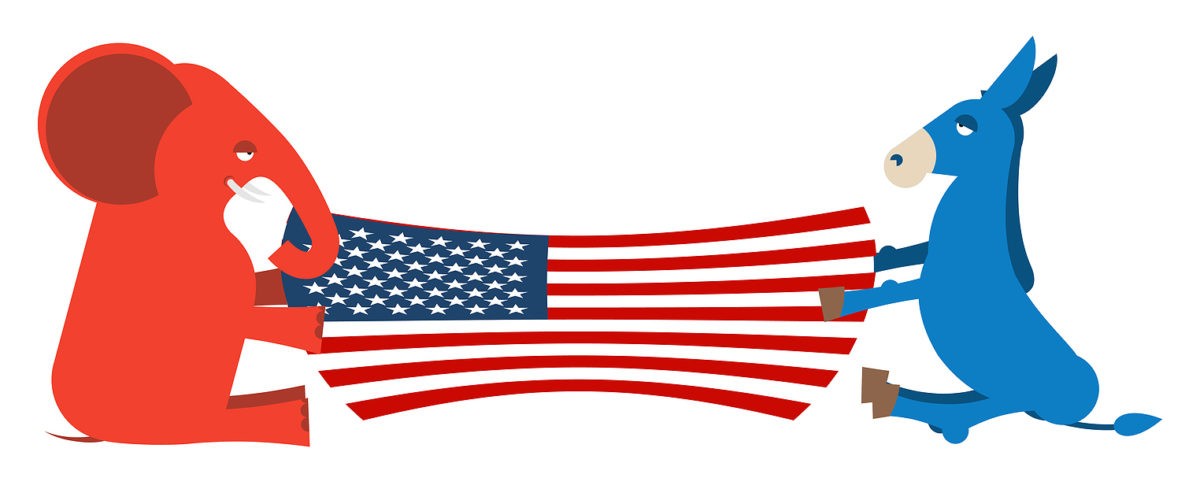

“Americans stand out for being more ideologically divided than those in the Western European countries surveyed,” Pew said. “For example, on whether the country will be better off in the future if it sticks to its traditions and way of life, the gap between the left and right in the U.S. is 59 percentage points — more than twice the gap found in any other country (the U.K. is the next most-divided country, at 28 points).”

“Americans stand out for being more ideologically divided than those in the Western European countries surveyed.”

Through polling and focus groups involving more than 4,000 respondents in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the U.S. in late 2020, Pew probed factors that influence opinions about national identity.

On both sides of the Atlantic, Pew said, fewer believe that people must be born in the U.S., Britain, Germany or France to be true citizens of those nations. Likewise, fewer said they believe someone must be Christian, embrace national customs or speak the dominant language to belong.

“People in all four nations have also become more likely to believe that immigrants want to adopt the customs and ways of life in their countries. Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) now hold this opinion, up from 54% in 2018, and the share of the public expressing this view in Germany has jumped from 33% to 51% over the same time period,” according to the study.

“People in all four nations have also become more likely to believe that immigrants want to adopt the customs and ways of life in their countries. Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) now hold this opinion, up from 54% in 2018, and the share of the public expressing this view in Germany has jumped from 33% to 51% over the same time period,” according to the study.

Additionally, a growing number of respondents said the four nations will be better off if they are open to changes to traditional ways of life. “Still, this issue is divisive, as a substantial minority in every country prefer to stick to traditions.”

Other major sources of division are views of political correctness and issues of concern about the well-being and feelings of others.

Four-in-10 respondents in each nation told Pew it’s important to avoid offending others while about 50% in each country, except Germany, said people take offense much too easily.

Except in France, a majority said it’s a bigger problem to be blind to discrimination that actually occurs than it is to see discrimination when it doesn’t exist.

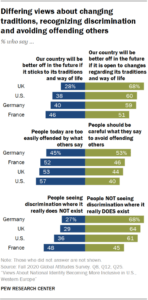

Pew also found disagreements over which groups are being discriminated against.

“In the U.S., for example, nearly half say Christians face at least some discrimination, though fewer than a third say the same in the European countries surveyed.”

In France, opinion is about evenly split on whether members of the Jewish community face discrimination while majorities in all four countries agreed Muslims are discriminated against, Pew added.

“All of these issues are also ideologically divisive. In every country surveyed, those on the right are more likely than those on the left to prioritize sticking to traditions, to say people today are too easily offended by what others say, and to say the bigger societal problem is seeing discrimination where it does not exist.”

The U.S. leads in being divided over political correctness.

Pew added that the U.S. leads in being divided over political correctness.

“The ideological divide in the U.S. is also around two times larger than that in any other country when it comes to whether people today are too easily offended by what others say (a 44-point liberal-conservative gap in the U.S.) and whether it is a bigger problem for the country today that people see discrimination where it does not exist (a 53-point liberal-conservative gap).”

Definitions and customs around citizenship also are dividing populations, Pew said. “Those on the right are also more likely to say each factor asked about — being born in the country, adopting its customs and traditions, speaking the dominant language and being Christian — are very important for being part of the citizenry.”

National pride has become a hot-button issue, with four-in-10 claiming to be proud of their countries “most of the time” while one-in-10 say they are ashamed of their nations “most of the time.” Meanwhile, “the balance say they are both proud and ashamed,” according to Pew.

But “in the U.S. and U.K., those on the right are more than three times as likely to say they are proud most of the time than those on the left. In these two countries, those on the left are equally likely to describe themselves as ashamed most of the time as to say they tend to be proud.”

For Americans, pride and shame often center on how the nation’s history is interpreted.

For Americans, pride and shame often center on how the nation’s history is interpreted, Pew said. Republicans tend to describe that past as a time of opportunity, while Democrats object to ignoring racism and poor treatment of minority groups.

“Republican participants, for their part, even brought up how political correctness itself makes them embarrassed to be American — while Democratic participants cited increased diversity as a point of pride.”

Conservatives and liberals in the U.S. also are widely divided on the meaning of being an American, Pew said. On the issue of language, 54% of liberals said speaking English is important, down from 86% in 2016. Conservatives saw a minor decrease in that attitude: from 97% to 91% in that period.

The survey also uncovered attitudes among respondents by age and religion.

In the U.K. and the U.S., Pew said, “Christians are more likely to say there is a great deal of discrimination against Christians in their society than against non-Christians.”

In the U.K. and the U.S., Pew said, “Christians are more likely to say there is a great deal of discrimination against Christians in their society than against non-Christians.”

Christians also were more likely to say being a member of the faith is essential to true citizenship and as a group are more likely to describe speaking the language and being born in the nation as key parts of national belonging.

“On other issues, too, they stand apart from non-Christians. For example, they tend to be more likely to say they are proud of their country and to favor sticking to traditions and customs.”

Survey participants under age 30, on the other hand, are much less inclined to hold those attitudes around customs, language and birth, Pew said. “They are also more likely to say their country will be better off if it is open to changes. The notable exception to this pattern is Germany, where opinion differs little by age.”