As senior airman Derek Tarr was flying over the Adriatic Sea in 1999, he suddenly realized he was being followed by a bright light.

“We started into a turn and as I look back, it’s just a bright white orb. It was bouncing almost like a super ball — very short, very succinct, very sharp movements, but extremely rapid,” he recalled. “The jostling or oscillations that it was doing were certainly not minute adjustments, probably several hundred feet, up, down, side to side … . In the blink of an eye, it just … shot right up in the sky. Fastest thing I’ve ever seen.”

A Department of Defense image of an unexplained object.

In a recent “60 Minutes” episode, Navy pilots described first-hand, eyewitness, video and radar evidence of vehicles that “can do 600-700 G Forces, that can fly at 13,000 miles an hour, that can evade radar, and that can fly through air, and water, and possibly space. And (have) no obvious signs of propulsions, no wings, no control surfaces, and yet still can defy the natural effects of earth’s gravity.”

Since that episode, the buzz about aliens has skyrocketed.

Former President Obama weighed in saying, “What is true … is that there’s footage and records of objects in the skies that we don’t know exactly what they are. We can’t explain how they moved, their trajectory … . They did not have an easily explainable pattern.”

U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio said: “There is stuff flying in our airspace. We don’t know what it is. We need to find out. I am going off what our military men and their radars and their eyesight is telling them. We need really some hard evidence, extraordinary evidence, because this would be one of the most extraordinary claims ever if it was true.”

Of course, we do not know for sure whether these UFOs are coming from an alien world. And while the upcoming congressional report is most likely going to neither confirm nor deny the existence of aliens, the evidence that these unidentified objects exist and have capabilities that far exceed what the highest ranked U.S. officials claim to know about modern technology has become undeniable.

Thus, Christians are once again having conversations about what it would mean for Christian theology if we receive confirmation of alien life beyond earth. Obama even speculated this week that “new religions would pop up.”

The Upside Down?

While speculation about UFOs may be a fairly recent phenomenon, the scientific and theological implications about life elsewhere is not.

As people began to realize that the earth was a sphere, humanity had to consider the possibility of people existing on the other side of the planet. They even came up with a name for such hypothetical life forms, calling them “antipodes.”

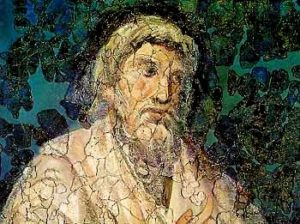

Lactantius

In the third century, Constantine’s adviser Lactanctius speculated, “How is it with those who imagine that there are antipodes opposite to our footsteps? Do they say anything to the purpose? Or is there any one so senseless as to believe that there are men whose footsteps are higher than their heads? Or that the things which to us are in a recumbent position, with them hang in an inverted direction? That the crops and trees grow downwards? That the rains and snows and hail fall upwards to the earth?”

St. Augustine was concerned more about the theological implications for original sin. He said, “As to the fable that there are antipodes, that is to say, men on the opposite side of the earth, where the sun rises when it sets on us, men who walk with their feet opposite ours, there is no reason for believing it. Those who affirm it do not claim to possess any actual information… . For Scripture, which confirms the truth of its historical statements by the accomplishment of its prophecies, teaches not falsehood; and it is too absurd to say that some men might have set sail from this side and, traversing the immense expanse of ocean, have propagated there a race of human beings descended from that one first man.”

A plurality of worlds?

Of course, now we know that intelligent life does exist on the other side of the planet. But what about on other planets?

Tycho Brahe

The 16th century astronomer Tycho Brahe refused to consider Copernicus’ idea about the earth revolving around the sun because he calculated that such a universe would have at least 300 million times the volume he had assumed. Of course, we now know that it is infinitely larger than that. He asked, “Why would God have created so much empty space?”

This led astrophysicist Paul Wallace to reflect in his book Love and Quasars, “He resisted a larger, stranger universe because he resisted a larger, stranger God.”

A depiction of Giordano Bruno being burned at the stake in the 17th century.

In the 17th century, however, Giordano Bruno was a poet who imagined an infinite universe where stars were actually suns orbited by planets filled with life. His curiosity and wonder led him to explore the convergence of philosophy, math, poetry and theoretical cosmology in ways that moved him to deny eternal conscious torment, embrace a theology of universal restoration, and question how much of our literal definitions of God were merely finite metaphors for the infinite. And for that, he was burned at the stake.

An earth-centered cosmos?

While modern conservative evangelicals are not burning people at the stake, they do share some common concerns with 17th century Catholicism.

Answers in Genesis warns that “the idea of extraterrestrial life stems largely from a belief in evolution.” Their theology of salvation does not give them space for aliens because “intelligent alien beings cannot be redeemed. God’s plan of redemption is for human beings: those descended from Adam.”

Dispensationalists steeped in “Left Behind” culture have been warning for years that the media will blame the rapture on aliens.

In his Systematic Theology, Robert Letham says the existence of aliens “would be no threat to the faith, since all it would entail is that such Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life would be incidental to God’s purposes for the human race.” He says these beings could be angels, fallen angels or the living creatures around the throne of God mentioned in Revelation.

“While the scope of the Bible’s vision for God’s reign is cosmological, it is also earth centered.”

These conservative theologians do have a point. While the scope of the Bible’s vision for God’s reign is cosmological, it is also earth centered. In Psalm 8, the entire cosmos exists as a hierarchy from God at the top above the heavens down through the divine beings and the humans below ruling over the animals on the land.

In the typical evangelical gospel story of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Restoration, the entire cosmos felt the effects of the fall based on Adam’s sin, including the farthest galaxies. This narrative would subject all alien worlds to the human evangelical story.

A new cosmolatry?

Elliot Nelson admits at BioLogos, “The possibility of alien life … forces us to ask what it means to be made ‘in God’s image.’” He says, “Christianity is cosmic. It makes bold claims about the nature and future of the physical universe … and must therefore face the challenge of modern cosmology.”

And thus, for Nelson and BioLogos, the challenge is “an opportunity to face apparent tensions and conflict with honesty and learn from them rather than smoothing over them, an opportunity to rethink what we think we know in pursuit of a richer and more imaginative — and indeed more faithful — vision of the story of Christianity.”

Ilia Delio

Ilia Delio, a Franciscan sister who teaches at Villanova University and is the founder of the Center for Christogenesis, has been a world leader in reimagining this cosmological story, saying, “Theology is integrally related to cosmology.”

Where would God be in a hierarchical cosmology? And how would that God relate to beings down the hierarchy? Of course, God would be at the top, as is reflected in Psalm 8. That’s the cosmology Jesus interacted with. He subverted it by revealing a God at the bottom of the hierarchy who ascends as a king to the throne of a cross.

But when the hierarchy is seen to be an illusion altogether, how does that affect our understanding of God and human identity? How does the hierarchy from God to humanity change when the earth becomes cosmologically de-centered?

Carl Sagan dubbed this religious narrative of earth-centeredness, “Earth Chauvinism.”

Andrew Burgess says, “As long as someone is thinking in terms of a geocentric universe and an earth-deity, the story has a certain plausibility. As soon as astronomy changes theories, however, the whole Christian story loses the only setting in which it would make sense. With the solar system no longer the center of anything, imagining that what happens here forms the center of a universal drama becomes simply silly.”

He coined the term “exoChristology” for theological conversations about how discoveries about space might affect our theology of Christ.

J. Edgar Burns speculated a half century ago that with our evolving understanding of our relationship to the cosmos, there may be a new “space-faith” developing, which he called “cosmolatry.” As a Catholic, Burns also was concerned about what this would mean for our understanding of Christ. So he coined the term “exoChristology” for theological conversations about how discoveries about space might affect our theology of Christ.

The universal Christ?

But why would our understanding of space affect our theology of Jesus? While I understand the desire Christians have to define the Christ strictly in terms of the deity and physical body of Jesus, the reality we find in Scripture opens our understanding of Christ beyond the simplicity of his physical body.

Colossians 1:15-20 says, “In him all things were created … . In him all things hold together… . Through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.” Here we see both a universal Christ in whom the entire cosmos is created, holds together, is being reconciled, and is expanding, and a bodily Christ who bleeds.

Ephesians 1:10 says, “to bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ.” While this reflects the cosmological hierarchy of being under Christ, it also introduces a convergence of universal unity in Christ.

An incarnation of converging love

Whatever differences we may have, Christianity eventually arrives at the incarnation. The concept of exoChristology becomes problematic when you consider the possibility of alien worlds having to be reconciled due to earthly sin. But what if the incarnation was not a reaction to sin?

Ever since Anselm, Western Christianity has framed the incarnation as Jesus coming to earth as a reaction to sin in order to solve a problem.

But for Peter Abelard, the incarnation was not a reaction to sin, but an overflow of love that was always going to happen because God becomes what God loves. And God loves the cosmos.

The Franciscan view of incarnation that spread through St. Bonaventure, John Scotus, and on through modern mystics like Ilia Delio and Richard Rohr is what Delio calls “a mystery of orderly love” that “uncouples the primary reason for the incarnation from sin and proclaims it as a work of love.”

Seeing the incarnation as an overflow of love that converges the entire cosmos into the Universal Christ gives us a framework for beholding an infinite mystery from a Christian perspective.

Liberating the earth

In her book Re-Enchanting the Earth, Delio says, “Jesus … had a new consciousness of relatedness, a new way of seeing others, a consciousness of the whole where each person is infinitely valued … . Love liberated Jesus into a new consciousness of wholeness. Jesus lived on a new level of existence, free from the oppressive powers of the world and from the past. He saw all creatures, human beings, the birds of the air, and the lilies of the fields, as part of himself.”

“When we consider the heavens, our posture must turn from ‘Earth Chauvinism’ to humility.”

Our task now is to participate in the liberation of the whole earth through love. And if we ever discover the existence of aliens, then we’ll begin the journey of integrating our stories together with theirs toward a consciousness of wholeness, of bringing unity to all things into a divine infinity that bleeds.

But each person must be infinitely valued. And for each person to realize the fullness of their value, they must be in the process of becoming whole and part of the whole themselves.

When we consider the heavens, our posture must turn from “Earth Chauvinism” to humility. If there are aliens out there, then our earth is but one perspective of the cosmos. In a sense, our earth becomes one person.

The person of Earth must become whole. For that to happen, Christians must move toward theologies of embrace rather than exclusion. We must move toward the longstanding tradition of love-driven atonement theories and the Christian mysticism of universal relationality where the entire cosmos is baptized in love.

Liberation theologies begin from the perspective of the person and move through love toward a web of relationality.

As we prepare for the possible future discovery of aliens, let’s embrace the larger, stranger God that Brahe feared. Let’s dream of infinite worlds as Bruno imagined. Let’s be willing to re-examine our theologies of hierarchy in light of the relational cosmos we now know we have. Let’s find beauty in the atonement models of Abelard, St. Francis, St. Bonaventure, and Scotus. Let’s explore the Christian mysticism of Delio and Rohr. And let’s humble ourselves in becoming whole by following the lead of liberationist theologians who can model for us how love can liberate the earth from all oppressive powers toward a consciousness of wholeness where each civilization from across the universe is infinitely valued and immersed in love.

And if we ever are able to confirm alien civilizations, then let me be the first to suggest that we change our name to Baptist News Universal.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock serves this summer as a Clemons Fellow with BNG. He is a recent graduate of Northern Baptist Theological Seminary and lives in Greenville, S.C., with his wife, Ruth Ellen, and their five children. Most days, he’s a stay-at-home dad but he also is a musician and author.