In this land where we’re supposed to have a free press, ensuring a range of perspectives on any given topic, I’m finding it hard to see any difference at all between various media outlets in their news coverage on Cuba.

MSNBC doesn’t deviate from Fox News; Sean Hannity on A.M. radio is reading from the same script as Lulu García Navarro on NPR; the Washington Post might as well be copying and pasting from the Drudge Report. Here’s the prevailing narrative: Cuban freedom fighters filled the streets on July 11 to take on tyranny, boldly shouting “down with the dictatorship,” and the oppressive regime has been harsh in its violent crackdown.

The storyline is coupled with the call to “stand with the Cuban people.” What Marco Rubio and the Miami Herald mean by this meme is very different from what I have been hearing over the past weeks from “the Cuban people” I know and love.

What Cuban people are saying

Stan Dotson

Late Sunday afternoon on July 11, I started getting texts and phone calls from one end of the island to the other, and here was the message I was hearing: “We are safe, at home. We are not on the streets. Please pray for calm.” While there were thousands who took to the streets that day, there were millions more who did not. Their story is not being told.

While no one I know is happy with the government response, the call from the Cuban people in my circle has been for calm, for peace, for dialogue. Mostly, their call is for everyone to stay focused on the current priority: surviving COVID.

That there is a raging pandemic coupled with scarcity of basic medicines, increasing food insecurity and complaints about government decisions is indeed a reality in Cuba. But how we frame a story is critical to how we understand reality.

The Cuban-American lobby here has been successful in dictating the story for the U.S. media across all outlets. For them, it was an Independence Day in the making. For many people in Cuba, though, the significance of July 11 has a lot more in common with Jan. 6 than it does the Fourth of July, and they are wondering who in the U.S. is going to stand with them.

Jan. 6 vs. July 11

Think about the parallels between the news-making events of Jan. 6 and July 11. In both instances, the manifestations followed a long and consistent campaign of media messaging, designed to create deep discontent. In our case, the messages were aimed at making people believe the democratic system is rigged, corrupt; Washington is a swamp to be drained; the leaders are evil. Our messaging culminated with President Trump’s mustering the troops, sending his supporters on their march to the Capitol to overthrow the system and re-instate the strong man as their ruler. In the case of Cuba, the messaging we have consistently sent their way is not so different, aimed at making people believe that the socialist system is rigged, corrupt, a gulag to be liberated; the leaders are evil.

“In both instances, the manifestations followed a long and consistent campaign of media messaging, designed to create deep discontent.”

In our context, constant tweeting and daily talk shows proved the point that no matter how outlandish the proposition, if you say it loud enough and repeat it long enough, people will believe it. While we in the U.S. have endured around 15 years of such messaging, beginning with challenges to the legitimacy of Barack Obama’s presidency, the Cuban populace has been receiving a similar bombardment of psychological warfare for 60 years, funded by millions of federal dollars. This barrage of broadcasting through radio and social media has been part of a broader national strategy, designed to achieve the stated policy goal of “alienating internal support through disenchantment and disaffection,” leading to an ultimate “overthrow of government” (State Department memo on Cuba from 1960).

Another January/July parallel: The claim of “peaceful protests.” Trump and his supporters continue to invoke that phrase for Jan. 6, decrying the ongoing investigation as an abuse of power. It’s the same with media coverage of Cuba: we are told the demonstrators were engaging in “peaceful protests,” conjuring up images of ’60s-era civil rights marches. But those who want to paint July 11 in terms of an MLK-style movement should remember that King and his followers were not marching to overthrow a government; they were pressuring the government to enact policies in alignment with the stated core values of a system they supported. Throughout our history, there have been these kinds of reform movements aimed at creating more coherence between our stated ideals and our lived reality.

In recent Cuban history, we have seen similar reform movements. People have taken to the streets to march for LGBTQ rights, striving to align public policy with the core values of the Revolution. And we have seen conservative evangelical groups marching to limit those rights, pushing for reform in a different direction. The dialogue around marriage equality has been robust, and continues, providing examples of “peaceful protests.”

Insurrection and sedition?

By way of contrast, when you have people marching with signs of “Down with the Dictatorship,” calling the president a murderer and shouting for an overthrow of the government, it is more in the historical vein of insurrection and sedition. Governments do not generally react well to these threats. We have our long history of how the federal government has used the full array of its force to put down what was perceived as insurrection: the massacre of labor union organizers on Blair Mountain in 1921; the murder of Black Panther leaders in 1969; the raids on Ruby Ridge and Branch Davidian compounds in the early 1990s; and the continuing response to Trump’s domestic terrorist action on Jan. 6.

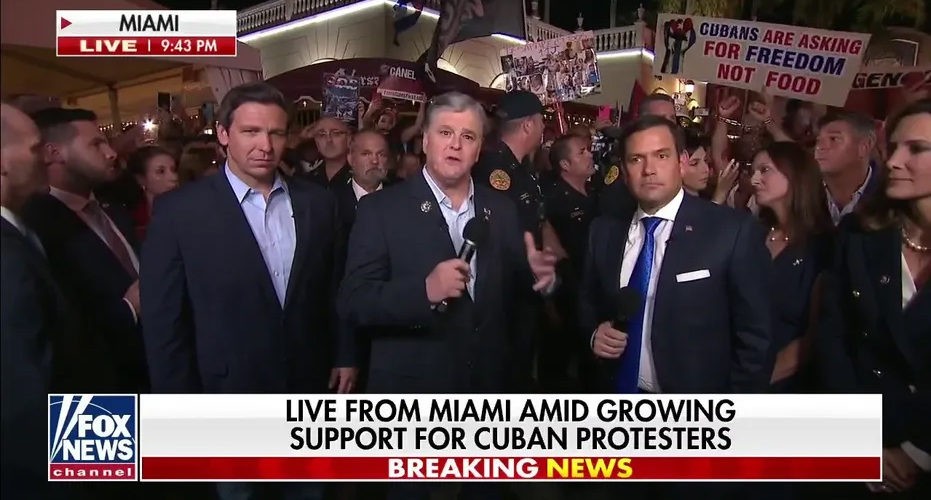

Cuban exiles rally at Versailles Restaurant in Miami’s Little Havana in support of protesters in Cuba on July 11. (Shutterstock)

Another parallel: Our media reports that in Cuba hundreds of July 11 marchers have been detained and arrested; they are generally characterized in the news stories as “political prisoners.” At the same time, here in the U.S., close to 600 people have been detained and arrested for their part in the Jan. 6 insurrection, some for violent offenses, but most for non-violent actions that contributed to the rioting. Only the most extreme of the right-wing press characterize them as “political prisoners.”

And another similarity: Our media rails at the Cuban government for the internet blackouts that occurred in the days after the protests. Again, isn’t this similar to what happened here after Jan. 6, with our government shutting down the Parler social networking platform because of its role in orchestrating the insurrection? The former president has had his own personal “blackout” from Twitter and Facebook for the same reason.

Belief in the system

A final correlation: A fundamental belief in the system. Despite all the flaws that have been revealed over the past few years in the U.S. system of government, there is still a commonly held core belief that that our system can work, that “America” is beautiful, even as we pray for God to “mend thine every flaw.”

“When I hear people here maligning the Cuban government as an evil ‘dictatorship,’ I think of my friends there who continue to maintain faith in the core values of their system.”

That core trust in our firm foundation provided the grist for so many Senate-floor speeches on the night of Jan. 6. The same is true for many Cubans regarding the Revolution.

Likewise, when I hear people here maligning the Cuban government as an evil “dictatorship,” I think of my friends there who continue to maintain faith in the core values of their system, some of them participating as members of the government. They have spent their lives working to fulfill the core values of the Revolution, to correct its errors and “mend its every flaw.”

There’s Raúl Suárez, Baptist pastor and founder of the Martin Luther King Center in Marianao; Christian ethicist Miriam Ofelia Ortega; the late Oden Marichal, Episcopal priest and founder of the Inter-Faith Platform for Peace; Manuel Hernández, beloved artist and political cartoonist. They all served for decades in the National Assembly (Cuba’s version of Congress). And now the assembly includes younger Christian leaders, such as María Yi, a Quaker pastor.

It may be a complete fantasy, but I do wish that our U.S. journalists would exercise their free press rights and not simply act as a tool of our government’s destabilization efforts. If our people could actually hear some of the voices of their people, hear how they frame the narrative, we might understand better how to stand with them.

Stan Dotson has served for the past three years as associate pastor of First Baptist Church in Matanzas, Cuba. He and his spouse, Kim, are currently back in North Carolina on a brief respite, awaiting their next opportunity to return and continue the work. Stan and Kim love their work of building bridges between Fraternity of Baptists churches in Cuba and congregations in the States, and they also love engaging in creative ministries of music, drama and storytelling. They have led more than 40 groups to visit churches in Cuba, beginning in the 1990s.

Related articles:

How to read the Cuban street protests in light of U.S.-Cuba history | Analysis by Ken Sehested

You want Patriotic Education? Look what it’s done for Cuba | Opinion by Russ Dean

A Cuban pastor’s response to President Trump’s Cuba policies | Opinion by Francisco Rodés