In February last year, David Oyedepo announced that his Nigerian-based church was going to establish 10,000 new branches in Nigeria.

Such a gigantic goal raised more than a few eyebrows.

Living Faith Church Worldwide, also known as Winners’ Chapel International, is considered one of Nigeria’s most popular churches, with branches within and outside the country, including in the United States. Yet even with such a large presence — more than 275,000 people in weekly attendance — observers wondered how Oyedepo and his team hoped to achieve such an enormous goal.

That skepticism gained even more traction when the coronavirus pandemic hit one month later, leading to lockdowns and restriction of movements and economic activities in many countries, including Nigeria.

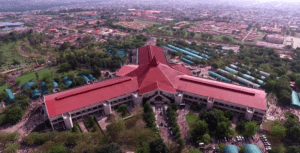

The Canaan Land compound of Winners’ Chapel Church in Nigeria.

In spite of the challenges witnessed throughout 2020, Oyedepo, in December of that year, declared the goal had been met. “In spite of COVID-19 noisesome pestilence, we planted 10,000 churches without raising an offering,” he said, adding, “We will show the devil and his agents pepper.”

Pastors let go en masse

A few months after that declaration, however, the feat suddenly turned to controversy when media reports revealed that some of the newly recruited pastors — estimated at more than 40 — already had been sacked.

One of them was Peter Godwin, who served at the church’s branch office in Ikere-Ekiti, in the southern part of Nigeria.

A video interview of his experience was posted online, in which he says he was “privileged to be one of the pastors” employed by the megachurch beginning in August 2020. “After that, I (went about) my duty to the Lord Almighty, trying my possible best to make sure I win souls to Christ.”

Then on July 1 of this year, 11 months into his role, Godwin was summoned by his regional leader, as were others. They all were issued letters of release from their pastorates. Godwin said he was told his “church growth index” fell below expectations and thus his service as a pastor was no longer needed. He was asked to vacate his official accommodation and hand over the church’s property in his care to the area pastor before leaving.

Godwin said he was told his “church growth index” fell below expectations.

When he called church management the next day for clarification, he was told that the church does not operate at a loss and that the total income generated from his station was supposed to cover his welfare and accommodation. Since that didn’t happen, he was relieved of his position.

Fuel for critics of the church

The story of the pastors being sacked led to a media frenzy in Nigeria, with respondents reacting in favor of or against the church’s leadership decisions.

Some of the critics argued this demonstrates that the Christian church has been turned into a business contrary to biblical teachings. But Oyedepo, for his part, has a different view.

Responding to the critics, Oyedepo said: “People are confused about our ministry. I learned that some fellow said, ‘You know, they are not bringing income, that is why they asked them to go.’ We asked you to go because you are unfruitful. Unfruitful! Blatant failure. Doing what there? We have no patience with failure here.”

“We asked you to go because you are unfruitful. Unfruitful! Blatant failure.”

He wondered where the critics were when the church was employing people.

“When we employed 7,000 people at a time, social media was dead. We have more employees in this organization than most of the states,” Oyedepo said. “No one is owed a dime salary, and we don’t borrow, we don’t beg.”

The church reports having started more than 21,000 branches since 1983. How many of those are still operating is not made known.

Not an isoalated story

Oyedepo’s rationalization aside, the Winners Chapel story is not isolated, as cases of pastors being hired and fired at will for one issue or the other are legion in the country and region. Still, these raise questions about the modus operendi of churches, not only in Nigeria and Africa but the world at large.

In an article titled “Why It’s Good to Run Church Like a Business,” Justin Lathrop argues that churches should be run more like business. “Before you write me off completely and tell me about Jesus turning over tables, hear me out. I think implementing best business practices in our churches today can help us serve the greatest number of people in the most helpful ways.”

This is so, he said, because churches have financial responsibilities. “It’s a fact. You either rent or own the building where you meet. You employ a staff, whose salaries you have to pay. You have lights you must keep on and programs you must fund and people to pay to care for your kids. Even churches with a bare-bones budget have things to pay for.”

Diarmaid MacCulloch

It’s true that the church always has needed to finance its activities, but what is bad is when people exploit their position for personal gain, said Diarmaid MacCulloch, emeritus professor of the history of the church at Oxford University.

In an interview with BNG, MacCulloch said his analysis of the business aspect of the church shows this is not new.

“Throughout Christian history since Christian congregations became permanent institutions, they have had a natural need to meet their expenses — to begin with, from members’ contributions in cash or goods, later with endowments of land and property from which an income could be drawn,” he said. “The classic Western Christian means of doing so was tithe: a tenth of farming produce given to the church, with a precedent in the Old Testament. At all times, this income has tempted people to exploit it for their own interest in a corrupt fashion.”

A 2019 Lake Institute on Faith and Giving study of congregations economic practices in the U.S. revealed that churches’ needs, irrespective of denomination, are similar. What often differs is the size, location and number of congregations. The study showed that “overall, how congregations receive, manage and spend demonstrates the diversity of their economic practices.”

What usually differs is the personalities calling the shots.

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who currently lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.