I was born outside this country, this culture and this language. Seeing myself as a citizen of the world and part of the one human race, I wonder if I have any words to say to you who read this in your maternal language and from the richness of your own culture.

As you read, please indulge a brother coming from the other America, in the South, ignorant of better words but who has seen death, suffering, violence and exclusion. I am someone who has witnessed despair, anguish and sadness, but also the joy of faith, hope and love as a magnificent flower growing in the rotten mud nurtured by the Spirit given by the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Juan Carlos Esparza Ochoa

Thus, as a Christian often seen as a foreigner, I have seen that the question “who is my neighbor?” — which may seem very simple — can be the starting point of difficult conversations. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought others in need and suffering so close to each one of us that we do not need to see far away to find someone who is close to death.

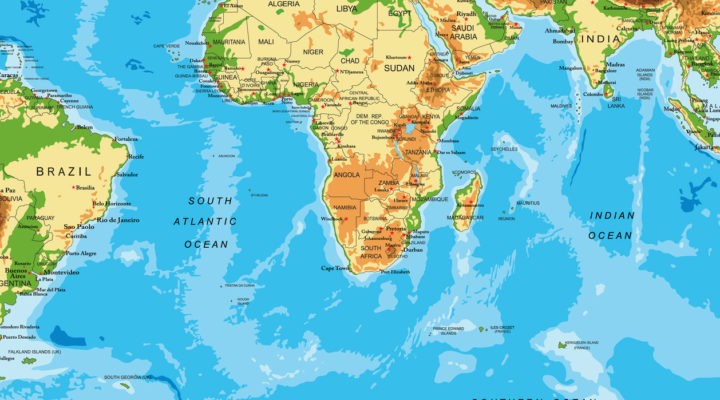

But the close view is not the whole picture. The pandemic also has reminded us that disease touching someone can spread suffering in the other side of the world and end up affecting the whole earth because humankind is really one family. We already knew that because we see ourselves as children of the same Father. However, in this immense family it has become increasingly easy to forget some of the siblings we rarely see and who are (almost) never in touch with us. It is perhaps easier to overlook those many faraway neighbors whose problems and sorrows can be easily ignored since they are a part of the other side of the world.

Nevertheless, they also are our neighbor. They are important to us for Christian reasons but also for many reasonable motives. The globalization we experience has shortened distances in such a way that we are living in the most multicultural societies known through human history. It is undeniable that Southern countries and their cultural richness cannot be ignored in any effort to fully understand contemporary Northern countries’ diversity.

“In this immense family it has become increasingly easy to forget some of the siblings we rarely see and who are (almost) never in touch with us.”

The approach to the South is also a learning opportunity. Any approach from a powerful standpoint to those lacking such power has the risk of turning relationships into colonial conquer and dialogue into cultural colonization. It is not enough to argue that they come from the best wishes and that something is better than nothing. This can be true, but still unintended consequences can be harmful.

I remember that I started practicing social work intervention when I was 15 years old. In our school, we divided in teams organized to visit and work weekly in a marginalized community. We started developing health community programs, including dog rabies vaccination. There is always a lack of medical personnel, so a group of 90 teenagers were trained for 20 minutes — in total — by a nurse. We practiced giving vaccines using an empty syringe and an orange. Even assuming the best intentions, the needle ended in the wrong place more than once. The result helped to prevent rabies, but as you can imagine, there were some dogs unable to properly walk after having been “helped” by our group. It was better than nothing, but it was not good enough.

Something similar occurs in some U.S.-born initiatives full of love and goodwill but lacking the appropriate strategy and cultural awareness. I have seen how amazingly easy it is to turn a teaching initiative into an intellectual colonialism enterprise.

Starting by language and including the neglect of local perspectives, pastoral training can become the effort of making African or Latin American pastors “in U.S. pastors’ image, according to U.S. pastors’ likeness.” This effort seems to forget the Deuteronomy (6:4) creed, “The Lord our God, the Lord is one!”

On the contrary, if Northern-born initiatives strive to become Southern born, learning from the other’s richness, they can stop being colonialist to become dialogue, education, evangelization. Dialogue itself turns the margins into the center, the excluded into the included, and the discriminated into an equal interlocutor.

This is necessary, but not easy. Dialogue-based interaction and intervention requires that the one from outside learns to listen to the others and to understand their own language. Those proposing initiatives must learn to stop speaking in their power-based language — and to stop speaking to themselves, as sadly happens many times.

“Those proposing initiatives must learn to stop speaking in their power-based language — and to stop speaking to themselves, as sadly happens many times.”

My 15-year-old ambiguous intervention story also shows that the South has conditions that go beyond usual Northern experiences and conceptual references. Whereas people in the North wonder if they should accept a vaccine, people in the South wonder how to have access to the vaccine to stop death. In the South, there are limited resources, limited structures, limited rule of law, but so many needs. There are places with an unbelievable insecurity, where life risk goes beyond Northern horror stories. I have seen an infant who starved to death. I have been in places with no running water — not even clean water — around them.

Adjacent to violence and corruption, there is a higher cultural appreciation of family and elders, more respect for religious practices and traditions, and an amazing disposition to help and share. To approach those Southern neighbors, dialogue can be the starting point. Wisdom and experiences as well as resources and strategies from everywhere are called to be integrated. We all have an open path to keep learning and practicing social innovation.

The Christian challenge is acknowledging that the Holy Spirit as the gift of the Father of Jesus Christ makes us all his children. I cannot be a child of God if I agree on excluding other sisters and brothers from the same table, from safe and healthy life conditions, from dignity, from freedom.

I came from the South keeping in mind those needs, and I decided to stay in the U.S. to access better opportunities to approach Latin America and the Global South. When I am not in need and pain, I tend to forget how pain hurts and how need stresses.

I pray that all I do will somehow favor the racially and otherwise discriminated, the colonized and destroyed cultures, the abused women, the neglected children, the abandoned elders. That is, I pray that all I do will somehow favor all those women and men whose blood also runs in my veins, because we are the same family.

Juan Carlos Esparza Ochoa is a leading expert on religion across Latin America and the Global South. He serves as director for the Program on Religion and Latin American Studies at the Institute for Studies of Religion and as a research assistant professor at the Diana R. Garland School of Social Work, both at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Related articles:

Loving your global neighbor | Opinion by Knox Thames

Loving my neighbor by being an ‘active bystander’ | Opinion by Becky Ankeny