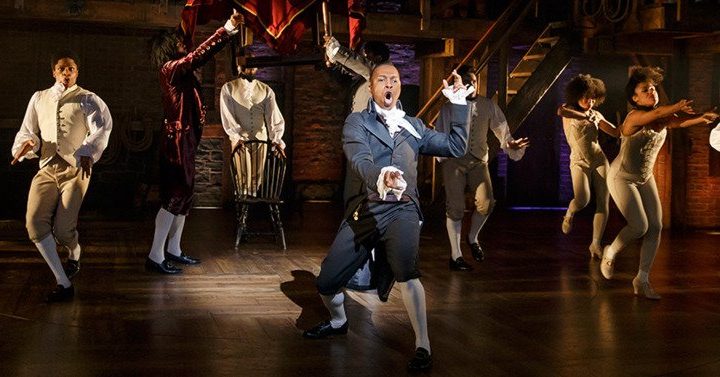

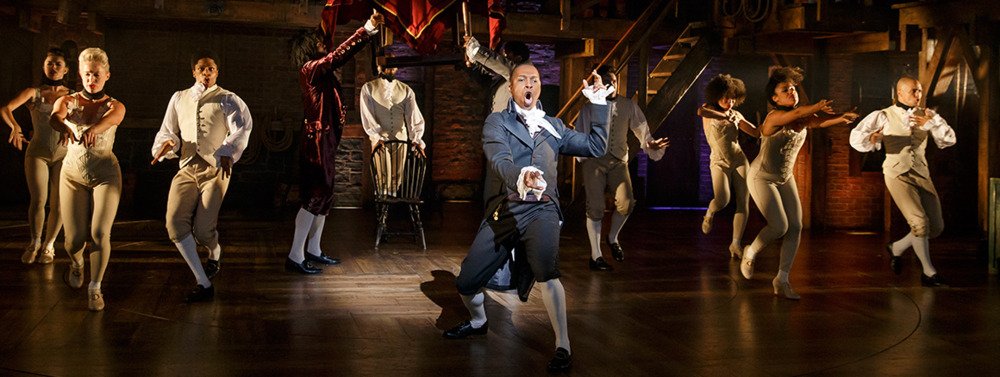

If you’re familiar with the Broadway musical Hamilton, then you’ve probably heard the song “You’ll Be Back.” Sung by the character of King George III, this song is a sharp shift in style and tone from the rest of the show and serves to remind the colonists that their attempted revolution inevitably will be just a passing phase. Because, of course, as the king reminds, they’ll be back; he can’t imagine they won’t.

It wasn’t until this past week that I was struck by the irony of just how tragically perfect that song is for this time.

Rob Dyer

Think about it: an authority, who thinks he’s in touch with his people, sweetly sings a song of truth to remind them, compel them, threaten them to return. Assured they will, he recites with disdain their reasons for distancing and counters each one with his own version of reality. As we know, the colonists did not come back. The revolution went forward. And those who once were citizens survived, nay, thrived without the home they once knew.

Living within the collective trauma of the pandemic, many people have stepped back from their churches. One of the responses from church leaders has been to lament decreased attendance, volunteer shortages, emptier rooms and reduced giving. While the message of such a response might be conveyed with a mindfulness of people needing the church, the motivation is not without the awareness that the church needs the people, too. How will we survive without their offerings?

This may sound harsh, but we are dangerously close to thinking of the people as numbers and seat-fillers we need — barely a step above property.

While we aren’t pulling a full King George III impersonation here with violent threats, there has been disdain. Expressions of frustration and disappointment with people have been shared in a multitude of ways including (but not limited to) passive-aggressive “invitations” in weekly church emails, non-specific but pointed social media posts, and maybe even face-to-face. I’ve seen it, my colleagues have seen it and, in the end, such a stance with our stanzas will probably produce the same result as that tired king: They won’t come back.

“This may sound harsh, but we are dangerously close to thinking of the people as numbers and seat-fillers we need — barely a step above property.”

In working to figure out this reality in my own context, here’s where I’ve landed: Collective lamenting has its place.

Ever since publishing my column “They’re Not Coming Back,” I’ve been overwhelmed with emails, phone calls and social media interactions with church leaders from around the nation who are feeling the pains, fears and confusion of this situation. To be honest, it was so humbling and healing for me simply to be heard and know that I am not alone.

But we can’t sit in the land of doom and gloom forever because the gospel is bigger than all this. The world still desperately needs a church that shows up where the people are, even if the people aren’t where we are.

In part one of “They’re Not Coming Back,” I shared three steps for addressing this new reality of absent individuals:

- We need to stop telling stories we know are not true.

- We need to see this situation for what it is.

- We need to understand why.

It’s with this last one that I’d like to springboard into a more specific idea every church in every town can do next: We need to become spiritual trauma centers for our communities.

What it means to become a spiritual trauma center

In many circles, “spiritual trauma center” is a term used for organizations that are trying to help people recover from unhealthy church experiences or other religious trauma. When I use this term, I am more generally speaking of the way we can reframe the role of the church in any community to address trauma from a spiritual perspective.

The church is called to see the real pains of the human condition and then to offer the good news in response, with hopeful reframing and merciful actions. When we do this well, we become a spiritual trauma center for the everyday and the extreme situations of life (like, let’s say, a global pandemic.) Trauma-informed ministry teaches us that we are interacting with wounded people who need help reframing the narrative of how they see themselves in the world and in the image of Christ.

“Trauma-informed ministry teaches us that we are interacting with wounded people who need help reframing the narrative of how they see themselves in the world and in the image of Christ.”

What it does not mean

We cannot approach this work with secret goals of increasing membership, attendance or giving. Our goal should be to help heal the wounded and show them a path that leads to life abundant.

This means the answer to the collective trauma of the pandemic is probably not found in simply attending our worship services. Our worship services can be good and important, but they aren’t so great that all the world needs is 52 Sundays of perfect attendance to experience real healing and wholeness.

Hosea 6:6 and Matthew 9:13 teach us that God desires us to be agents of mercy more than robots of ritual. If we succeeded in bringing all the people back to regular worship, weekly serving roles and consistent giving, but never helped them heal from the spiritual trauma of the pandemic, that would just be “noisy gong and clanging cymbal” ministry. Sure, our seats would be filled. But then when they return to all the other seats they fill every other day of the week, how will they be doing, really?

How to be agents of mercy

First, get everyone in your congregation their own “agent of mercy” cape. They’ll blow everyone away as they walk through town, ready to care for others.

Actually, the first thing to do is recognize your unique setting and context and consider where you can start. Not everyone in your congregation is ready — or able — to take these steps. And that’s OK.

“The first thing to do is recognize your unique setting and context and consider where you can start.”

The encouraging news is you don’t need everyone to start doing this work. In fact, none of the steps to becoming a spiritual trauma center require that you get your church’s permission before trying. And nobody is forced to participate (of course.) But the offering of what you’re about to endeavor to try will, hopefully, start to impact in ways so that others are drawn to be a part. It also should be noted that the more people who engage in this work, the more likely you’ll find yourself leading a church that is a spiritual trauma center for your community.

Practical Step No. 1: Learn to listen for people’s particular pains.

When you talk with people, whether an estranged member or someone new who you want to reach, actively listen to what they are experiencing and don’t worry about a response. When people talk about what life is like for them now, don’t try to solve the problem or give your own examples. Just listen to people with the hope that you will learn something and maybe even be changed by what they share. There is healing in being heard and wisdom in listening.

Taking notes while you are listening to people can be awkward unless you are chatting over the phone. So, as soon as you wrap up talking with someone, give yourself time to make notes on what you heard and think deeply about what they have shared with you.

“There is healing in being heard and wisdom in listening.”

If you are in tune with the needs of real people, then your prayerful discernments for the actions of your ministry will be better grounded in the actual human condition, the actual pains of the people. You have an answer for these pains in the next two steps. When the timing is right, trust that the Spirit will guide you in sharing this answer.

Checkpoint No. 1 to becoming a spiritual trauma center: Do you know the particular pains of the people you are trying to reach?

Practical Step No. 2: Be ready to articulate the benefits of following Jesus.

How many of us can actually articulate the benefits of following Jesus? When the people in pain open their minds and their hearts, do we just offer a series of wonderful worship services and programs? I hope not. I hope we find a way to fully articulate how Jesus has become the spiritual cure in our own lives — and can be in theirs, too.

As I type this, I know how ridiculously basic and simple this seems, but each of us needs an elevator speech. Each of us needs that 30-second “here’s why my life is better with Jesus” snapshot that explains why we’re different and life is different because of him. And then we need to have the deeper version for when someone asks for more.

“Can you genuinely explain the benefits of following Jesus in a way that is 100% authentic to your experience of life?”

Let’s be honest, most of our churches are filled with people who cannot do this. If both the leaders and the people cannot express why the good news is good, then does it really surprise us that connections with the church have grown so thin amidst all the terrible, very bad news that has monopolized almost every facet of our lives over the last 18 months?

Checkpoint No. 2 to becoming a spiritual trauma center: Can you genuinely explain the benefits of following Jesus in a way that is 100% authentic to your experience of life?

Practical Step No. 3: Invite the people into a generosity of steadfast love.

If we can find ourselves in church communities where both the pains of life and the benefits of the gospel are known, this next step should be easy: Start inviting people to join you in loving others.

Someone you know needs help. Go help them. Take someone with you. And experience firsthand how those physical, mental and emotional pains you learned about during step No. 1 begin to heal through acts of steadfast love from people of faith.

The collective trauma of the pandemic has been predominantly fueled by a lack of connection with others. People need people. And those needs aren’t met solely through a Sunday morning hour or Wednesday night dinner within our church walls. Such an expression of love responding to such a deep need will overflow into the streets of the surrounding neighborhoods and beyond time frames of convenience.

“We have got to start loving people so extravagantly that they ask us why we are doing it.”

We have got to start loving people so extravagantly that they ask us why we are doing it. And it will be in those moments that we will get to tell them about Jesus. Because he loves in these ways. And when we know and follow him, we can’t help but do the same.

Checkpoint No. 3 to becoming a spiritual trauma center: Are you loving people in extravagant ways with the help of other people?

Millions of people have seen the Broadway musical Hamilton. This means millions of people have heard the out-of-touch leader who’s too proud to acknowledge the needs of his people and instead continues offering solutions for problems they don’t have, eventually losing them for good.

Yet, in the second act of Hamilton, another song is sung. This one by a new kind of leader who simply wants to be in “The Room Where It Happens.” This leader wants to have a role in the important things. He wants to be a part of that which makes a lasting difference in the lives of the people.

There is a god of attendance that can demand our attention. There is a god of giving and a god of doing-what-we’ve-always-done that can drive our actions too. But then there’s the God of love. Our God sees pain, weeps with those who weep, offers healing truth, loves deeply and invites us to do the same.

Our God is not worried about how many seats are filled on a Sunday. Our God is wondering how many hearts will be seen and served by the people of God. If we choose this God of love in our churches, then I imagine many others will want to be in the room where it happens.

Rob Dyer serves as senior pastor at First United Presbyterian Church of Belleville, Ill. He has spent the last several years working in the areas of community missions and leadership development in Southern Illinois, where he lives with his brilliant and supportive wife, Sarah, and their four children. He also serves as lead consultant with Ministry Architects, where this column originally was published.

Related articles:

They’re not coming back | Opinion by Rob Dyer

It may take 21 Sundays, but I will get back to church | Opinion by Nora Lozano

What we missed most about in-person church, what’s coming back and what’s likely to change

In ‘Hamilton,’ King George has Calvin on his side | Opinion by Rick Pidcock