As Advent approaches quickly, focused on waiting for the Christ Child, and as we light the candles of hope, joy, love and peace, I find myself unready. Exhausted. Feeling out of touch with the patterns of the church year, with the cadences of the seasons, still struggling to find a new rhythm 18 months after COVID-19 changed our world.

And while people still long for “things to go back to normal,” we know deep down they will not, perhaps cannot, and maybe should not. The semblance of normal we had — I had — thrived on keeping things quiet that made me uncomfortable or pointed out my (and our country’s) sins. The normal I long for focused on a false unity at the expense of justice. The normal I experienced was an excess of busyness and neglect of Sabbath.

Kate Hanch

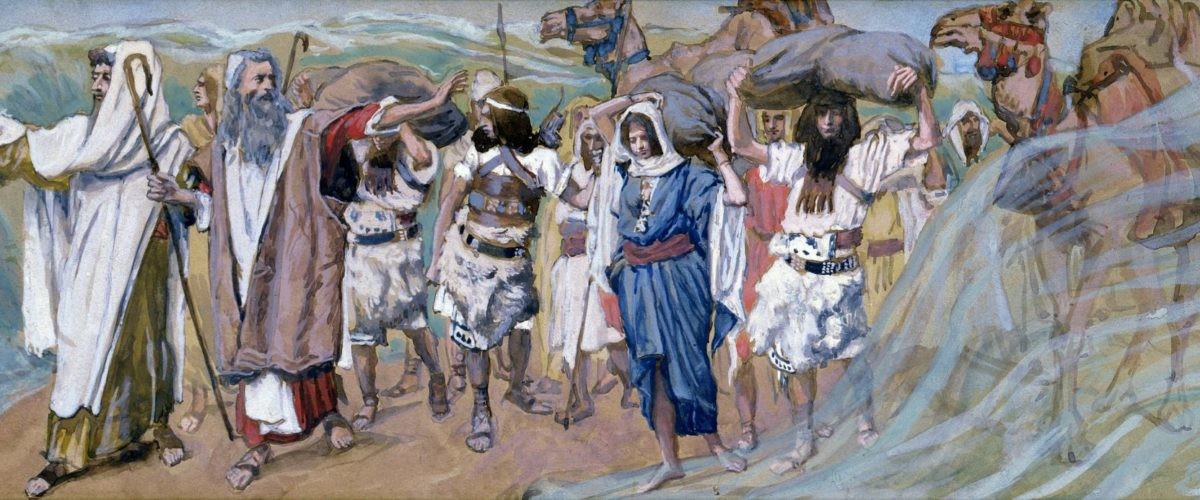

Just like the Hebrews longing for the certainty of Egypt as they staggered about in the wilderness for a long 40 years, we, too, prefer a certainty, a clear trajectory over the chaos that comes with the unknown. And many pastors find themselves in the role of Moses, listening to their congregations’ sadness and weariness, while experiencing weariness of their own. One can certainly connect with Moses’ conversations as he speaks with God — wondering why God doesn’t move more quickly.

In the wilderness, as they camped at night under the tents and around the fires, the Hebrews would turn toward their own history, songs and prayers that sustained them while in Egypt. They remembered the previous covenants God had made with their ancestors. Focusing on the past reoriented them to the present. God has sustained you, even when the odds were against you. God will deliver you. You will not be in the wilderness forever.

Could this be what hope looks like? Remembering the past, not as a means of naïve nostalgia, but as a way to uncover how God might be doing a new thing. This could be like Zechariah, John the Baptist’s father, who, in exclamation after his son is born, proclaimed:

“(God) spoke through the mouth of his holy prophets from of old, that we would be saved from our enemies and from the hand of all who hate us. Thus he has shown the mercy promised to our ancestors, and has remembered his holy covenant.” (Luke 1:70-72)

“At my worst, I find myself wondering if God has indeed remembered that promise to ‘guide our feet into the way of peace.’”

At my worst, I find myself wondering if God has indeed remembered that promise to “guide our feet into the way of peace” as Zechariah ended his proclamation (Luke 1:79) when I have yet to see peace in our justice system, in our communities, in my own heart. Hope’s stubborn insistence rings hollow to the state of our world and nation, where, for the first time, the United States has been declared a backsliding democracy. Where the Great Resignation includes caregivers like teachers, health care workers and pastors of all denominations. Where there appears to be plentiful jobs, but few at a living wage or adequate insurance. Where it seems everyone is at the end of their rope, with nothing left to give, and yet we have to hold it together for ourselves and others.

Julian of Norwich (Creative Commons)

I turn to Julian of Norwich again, like I did when COVID-19 first changed our lives, but with different lenses, my eyes a little bleary and my head hung lower. Julian lived 100 years before Martin Luther nailed the 95 theses to the Wittenberg door. Before COVID-19, I would joke with students and others that if Julian could bear witness to the Black Death, the burning of “heretics” (who would later be seen as forerunners to the Reformation), the decline of trust in the church, and political instability, we could make it through today. And then, as if God has a sense of humor, it seemed like all of those things happened here in the United States, 600 years later.

Toward the end of her Revelations of Divine Love, the revision of her original text written 30 years later, Julian riffs on Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians as she speaks about hope: “So (love) keeps us in faith and in hope, and faith and hope lead us in (love). And in the end all shall be (love).”

I don’t know how to always hold hope, even as we light the hope candle this Advent season. I may write about it a lot, but because it can feel like an enigma. But I do know what love looks like, and I see glimpses of love even as it seems as if hate surrounds us. And maybe by recognizing that love, by celebrating that love, and by seeking out opportunities to love, I pray the hope will follow. The hope has to follow.

Kate Hanch serves as associate pastor for youth and families at First St. Charles United Methodist Church in Missouri. She earned a master of divinity degree from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in theology and ethics from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. She is ordained in the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in O’Fallon, Mo., with her husband, Steve.

Related articles:

The Atlanta Braves and the window of hope | Opinion by Richard Wilson

I’ll get to hope. For now, I need to sit in the ashes and mourn | Opinion by Susan Shaw

What I learned from RBG about the ‘dissenter’s hope’ | Opinion by Jordan Conley