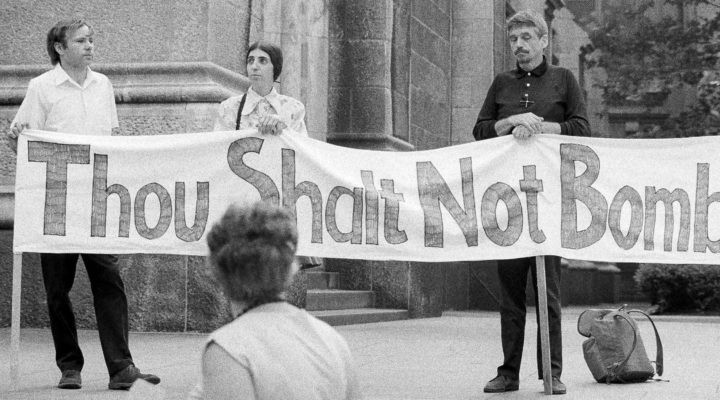

Veterans Day last week was disquieting to me, not because I do not join in respect for those who have fought, suffered injury and died for our nation. Remembering the sacrifice of others is a deep expression of human reverence. What disquieted me is the almost absolute and continuing silence of the Christian church through the years to honor and give thanks for the pacifists in our nation’s history who have refused to take up arms because of their obedience to Jesus.

These have done so at no small cost. So, these words in gratitude for pacifists, conscientious objectors and other followers of the nonviolent way of Jesus.

Stephen Shoemaker

Most early followers of Jesus in the first three centuries were pacifists. Then came the joining of church and state and the rise of what some call “Constantinian Christianity.” The Roman Emperor offered the church freedom from persecution. The emperor needed the church’s political help in unifying his empire, and we went meekly along. It is an enormous spiritual tragedy that the “peace churches” — Anabaptists, Mennonites, Quakers and more — have been such a minority witness in the church to the teachings of Jesus about nonviolence.

Growing up in Southern Baptist Land, what Carlyle Marney described “South of God,” I never heard a whisper about the nonviolent way of Jesus. What was good for the nation was, ipso facto, good for the church. There never could be a moral conflict between loyalty to Christ and loyalty to the nation. Military service was an unquestioned yes. A man in one of my churches who grew up in Kentucky told me that at the annual Royal Ambassadors summer camp (our sanctified Baptist version of Boy Scouts), there always was an Army recruiter present to sign up young followers of Jesus.

When I went to Union Theological Seminary in 1971, one of my teachers was the radical Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan. He had been paroled from federal prison to teach there. He, his brother and seven others had been arrested for pouring homemade napalm on draft files in protest of the Vietnam War.

As they came to arrest them, Daniel said as the liturgy over their sacrament of civil disobedience, “Pardon us, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children.”

“For a person to risk his life and well-being for peace as a follower of Jesus challenged my theology and messed with my spiritual complacency.”

All this was quite astounding to me as a Baptist boy from the South. For a person to risk his life and well-being for peace as a follower of Jesus challenged my theology and messed with my spiritual complacency. It sent me back to the Gospels, especially the Sermon on the Mount. “Blessed are the peacemakers …. turn the cheek … love your enemies?!” Nothing in Jesus’ life contradicted his words. At the end he chose to die by the sword rather than take it up, and he prayed forgiveness for his executioners.

It is a mark of our selective following of Jesus’ commands that young people in most churches I have known have been given little, if any, opportunity to talk with seriousness about nonviolence and conscientious objection to war. One of my beloved professors was Henlee Barnette, professor of ethics at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He and his wife, Helen, built a home and raised four remarkable children. During the Vietnam War one son went to war in Vietnam and his brother, following his own conscience, avoided military service by going to Canada. They blessed both sons. This should be a model for churches.

In Wendell Berry’s novel Jayber Crow, Jayber grew up in a typical Kentucky religious environment. Early he felt called to the ministry and went to a Bible college. Soon he realized it was not God calling him, and he went on to be a barber in his small rural town. He lived through the devastation that World War II brought to his community. At one point he said to himself: “I was glad enough that I had not become a preacher, and so would not have to go through a war pretending that Jesus had not told us to love our enemies.”

Many preachers live in this moral predicament.

We well honor our veterans, but let us also honor the Christian pacifists, the conscientious objectors, the wartime ambulance drivers, the teachers and poets and occasional preachers who have shown us the nonviolent way of Jesus.

How can we in our churches and nation better teach the honoring of the minority conscience of those who oppose war and the pervasive violence of our society? This past weekend, in response to the not guilty verdict in the Kyle Rittenhouse trial, North Carolina Congressman Madison Cawthorn urged his followers: “Be armed, be dangerous, and be moral.” Such is the state of piety and politics today. How can we speak to the almost continuous war in our nation since World War II and confront how the war economy of our military-industrial-corporate complex has distorted the budgetary priorities of our nation?

“How can we in our churches and nation better teach the honoring of the minority conscience of those who oppose war and the pervasive violence of our society?”

In 1569, Dirk Willems, facing capital punishment for his Anabaptist beliefs about baptism and pacifism, fled his captors. One pursued him across a frozen lake. The ice began to break underneath the captor’s feet, and he went under. Willems turned and pulled him out of the ice, saving his life. When they went ashore, he was arrested and was executed by being burned to death.

Perhaps one way to begin our moral education about Jesus’ way of nonviolence would be for Baptists to have an annual “St. Willems Day” and reacquaint ourselves about those in our tradition who have through the years taken the nonviolent teachings of Jesus literally and followed.

Advent approaches. The church will sing many carols and anthems about the birth of Jesus, some of them about peace. One could fill an entire Advent booklet comprised of Jesus’ words in the four Gospels about nonviolence and “the things that make for peace.” In a nation where many Christians are joining with those who say that violence may be necessary to defend their version of democracy, such a booklet would let us more truly worship the one we call “Prince of Peace.”

Stephen Shoemaker serves as pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Statesville, N.C. He served previously as pastor of Myers Park Baptist in Charlotte, N.C.; Broadway Baptist in Fort Worth, Texas, and Crescent Hill Baptist in Louisville, Ky.

Related articles:

Afghanistan: A tragic example of an unjust war | Analysis by Chris Conley

Peacemaking about more than ‘funky T-shirts and Birkenstocks,’ Baptist says

Activists reflect on Baptist peacemaking in wake of Stassen death