When Beth Moore left the Southern Baptist Convention in 2021 and soon after was seen in a photo serving Communion at an Anglican church, the social media outrage became a reminder that few people seem to rile up Southern Baptist and conservative evangelical TheoBros as much as Beth Moore.

At the Truth Matters Conference in 2019, which was a gathering to celebrate John MacArthur’s five decades of ministry, Todd Friel asked MacArthur to play a word association game with the two words “Beth Moore.” To which, MacArthur famously replied, “Go home.”

MacArthur’s henchman Phil Johnson added, “The word that comes to my mind is ‘narcissistic.’”

Then MacArthur jumped back in to say: “Just because you have the skill to sell jewelry on the TV sales channel doesn’t mean you should be preaching. … The church is caving in to women preachers. … Women are not allowed to preach.”

“Few people seem to rile up Southern Baptist and conservative evangelical TheoBros as much as Beth Moore.”

Attacked for being a Baptist and then for not being a Baptist

Over the next two years, many within conservative evangelicalism followed MacArthur’s lead and continued piling on.

In a recent episode of The Holy Post podcast, Phil Vischer reflected: “There was this movement in 2020 of people saying, ‘We have to be open to more perspectives. We have to hear more voices. We can’t always assume that we the majority — in this case white men primarily — are the ones who know what’s right about everything. … I describe 2021 as ‘The Empire Strikes Back.’ … There was such as strong pushback on people like Beth Moore and Russell Moore, who now neither are in the Southern Baptist Convention.”

Russell Moore was then head of the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission but resigned last summer rather than continue to fight the far-right flank of the SBC who thought he was a liberal. He now works for Christianity Today.

Regarding Beth Moore, Vischer said, “She was attacked for being a Southern Baptist but not quite towing the party line from the most conservative parts of the Southern Baptist Convention. Now she’s being attacked for not being a Southern Baptist.”

Vischer was referencing the fact that Beth Moore decided to leave the SBC and join St. Timothy’s Anglican Church, a congregation within the theologically conservative Anglican Church in North America.

Split image captured for social media and shared by critics of Beth Moore becoming an Anglican.

When Reformation Charlotte recently discovered that Beth Moore was wearing a robe and serving Communion in her new church, they called her an apostate, posted screenshots of the service and of the church’s volunteer schedule, and reminded the world of their prediction that “it would only be a matter of time before Beth Moore becomes full-on gay-affirming.”

But Moore’s journey from Baptist churches to Anglican churches is not unique. In fact, it is a journey many evangelicals take, including myself. There are many examples of Southern Baptist pastors, scholars and laity alike finding their way to the Anglican Church.

Of course, I am no longer a member of an Anglican church because my spiritual journey kept going beyond where the Anglicans were willing to go. And I cannot speak for Beth Moore’s journey, especially since I am in very different theological spaces today than where she is. But I can share some insights as to why the Anglican Church attracted my Baptist-formed journey, and how the Anglican Church opened me up to life beyond it.

Learning the language with independent fundamental Baptists

I grew up in the very conservative world of the independent fundamental Baptists. We primarily were concerned with the holiness of God, which we defined as separateness and took very seriously as a call to be “in the world, but not of the world.”

We applied that separation mindset by creating detailed lists of rules about hair style, dress style, music style, and virtually every area of life one could imagine.

We married our attachment to rules to a desire to be seen as balanced. For example, we were not KJV only. But we only used the KJV. This supposedly moderate position allowed us to feel safe by only using the King James Version of the Bible without being categorized amongst the more extreme KJV-only factions of independent fundamental Baptists.

“While there was much to fear in this world, it was the world that introduced me to the language of Christianity.”

While there was much to fear in this world, it was the world that introduced me to the language of Christianity. It was there that I first learned the stories of the Bible, heard about Jesus and was introduced to life in community. This language would become the framework through which I would spend my life processing ultimate reality.

Still, these rules, set within the context of fearing the holiness and immanent judgment of God, cultivated deep wounds that eventually would lead me out of this subculture.

Cultivating my curiosity with Free Will Baptists

Most independent Baptists believe in the doctrine of eternal security, which teaches that once a person says and means the sinner’s prayer, they are saved forever. One unique part of my story within the world of independent fundamental Baptists, however, was that my family believed Christians could lose their salvation.

Our denial of eternal security eventually led us to join the Free Will Baptists, who believe in Baptist distinctives while leaving room for the possibility that some Christians might choose to walk away from God and lose their salvation.

“Our denial of eternal security eventually led us to join the Free Will Baptists.”

Most Baptists practice the two sacraments of believer’s baptism and communion. Free Will Baptists add foot washing as a third sacrament of the church. While I wasn’t looking forward to holding the dirty feet of the Sunday school director, and although I do not believe the Bible requires foot washing to be practiced by churches today, the exercise invited me to wonder if there might be more opportunities to see a divine presence in spiritual practices beyond what I had previously considered.

Free Will Baptists also tend to have less-detailed lists of rules than independent Baptists, which allowed me to explore learning to play the guitar in church. Our repertoire was almost exclusively hymns and Southern Gospel music. So it remained a pretty limited experience. But it opened my curiosity for how my wonder could be expressed musically.

Still, the fear of losing my salvation amidst the tensions of purity culture and Left-Behind culture proved to be too great for me to stay with the Free Will Baptists.

Becoming myself with baptistic community churches

After I enrolled at Bob Jones University in 2000, I spent the next 17 years in non-denominational community churches that would often admit to being “baptistic.”

These churches were Calvinistic and complementarian in their theology, along the lines of Grace to You, Desiring God and The Gospel Coalition. We were fully committed to biblical inerrancy while using the English Standard Version of the Bible. We were unapologetic about penal substitutionary atonement and eternal conscious torment. And we were committed to being distinct from the world, while being allowed to use modern music styles, drink alcohol and go to the movie theater.

Our appreciation for the preaching and worship of Sovereign Grace Churches, a movement that labels itself as both Calvinistic and charismatic, opened us up to some levels of interest in broader experiences of spiritual gifts as long as they followed what we believed were the Bible’s guidelines for exercising them.

“We were able to garner their financial support by assuring them that we were ‘baptistic.’”

Yet, like the Baptist churches I grew up in, we were fiercely independent. So because we lacked the structural support of a broader denomination, those of us who were involved with church planting turned to organizations like Acts 29 or independent supporting churches. Those who knew us often were independent fundamental Baptist churches who disapproved of our standards and styles and the absence of “Baptist” in our name. But we were able to garner their financial support by assuring them that we were “baptistic.”

The result of this world was one where I was free to explore and express my desires and passions, to become more truly myself, and yet where I was tied enough to my conservative background to be held back from asking my questions and exploring any cognitive dissonance that would arise.

During my final year and a half in these baptistic community churches, I was introduced to self-awareness through reading such authors as Henri Nouwen and Richard Rohr, Catholics who valued the contemplative life. As I opened up to seeing and loving myself through contemplation, I began to see and love my neighbors as well. With this expanding awareness and love, my questions deepened until I began to realize how my conservative evangelical theology had been cutting me off from myself and my neighbors. Eventually, my awareness of the power dynamics in these churches made me realize it was time to move on.

Converging my entire journey into the Anglican Church

For a number of months, I felt very exiled, wondering if there were any churches out there who understood where I was coming from and yet would welcome my current questions more freely. And that’s when I was introduced to an Anglican church.

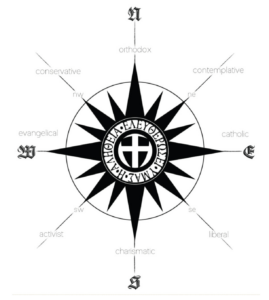

The Compass Rose

In The Anglican Way, Thomas McKenzie uses a concept called “the compass rose” to describe the directions of the Christian life as a series of spectrums between the personal (evangelical) and the communal (catholic), between the here (charismatic) and there (orthodox), between being (contemplative) and doing (activist), and between stopping (conservative) and going (liberal).

Anglicanism gave me the freedom to exist at various points of these spectrums, from the more moderate middle to the outer edges. It seemed like a dream come true for someone whose journey developed in me the very complex blend of theological and ethical priorities the compass rose named.

For many people who come from conservative Baptist backgrounds, finding the Anglican communion feels like coming out of exile and returning home to everything that had been growing in you for years. Beth Moore recently tweeted: “I love my church. I could cry about it. The Lord has so blessed me in the course of my life with wonderful church families. He entrusted many other enduring sorrows & hardships to me but somehow he chose that, just as church was a harbor for me in childhood, so it is in my aging.”

Opening up to all things new through the Anglican Way

The Anglican Church also began opening up new languages, curiosities and identities for me that I never imagined were possible.

The moment you walk into an Anglican service, one of the first things you’ll notice is the aroma of the incense. By the time you see the colors of the decor, hear the sound of singing, touch the hand of a friend, and taste the bread and wine, you will have experienced the present becoming of community and transcendence with all five senses.

The second thing you notice in Anglican services is the liturgy. For those who have spent their entire lives in non-liturgical spaces, this can be a bit of a culture shock, to sit through the amount of responsive readings and scripted prayers. But while my theology was shifting, the liturgies felt like anchors that were keeping me from getting swept away. And in the liturgy of the Eucharist, I could receive an experience of the presence of Christ with all my senses.

Thomas McKenzie

When the service ends, the Anglican Way is just beginning. Thomas McKenzie explains: “The Anglican Way developed in an agricultural society. … They didn’t experience a rigid distinction between the material world and the spiritual world. The church helped them remember the holiness of every moment by sanctifying (making holy) the natural patterns of the day.”

In addition to reciting liturgies throughout each day and week, Anglicans also utilize the church calendar. McKenzie says: “Beginning with the foundations of the Jewish calendar, the early church built a temple to God in time rather than space. Our spiritual ancestors measured out the days, weeks and months. They collected, sorted and named them. They put everything in place so that we, their children, would have a splendid palace in which to worship.”

In my experience, the Anglican Church became a cloister garden of particularly cultivated experiences that opened me to the universal reality across time and space. By engaging my five senses, I began to wonder how else I might embody the present becoming of community and transcendence with all things. By learning the liturgy, I became curious about other liturgies from other communities, including the liturgies of our Jewish, Muslim and Buddhist neighbors. By recognizing the spiritual in the material, I saw the significance of every person, plant and creature. And by experiencing the presence of Christ in the Eucharist, I began to receive the presence of Christ everywhere.

Expanding beyond the Anglican Way

One skill I’ve developed over the years within these various contexts has been to learn where people’s walls are. As a creative person, I tend to push over walls to discover what’s on the other side.

With the Anglican Church, I began to realize how women could serve Communion and even become priests but noticed all the bishops were men.

With the Anglican church, I began to realize that theological perspectives were greatly varied, but that our children in our particular church would be formed by teachers and curriculum that promoted some of the very harmful retributive and complementarian perspectives that had so deeply wounded my wife and me.

“With the Anglican church, I began to realize that theological perspectives were greatly varied.”

With the Anglican Church, I began to realize how the Anglican Church in North America kept LGBTQ people on the other side of the walls. McKenzie explains that when the Episcopal Church named Gene Robinson, a gay man, as a bishop in 2003, it was the “straw that broke the camel’s back. … His teachings and his lifestyle are not in alignment with Anglican values and theology. … His consecration went against all that bishops are supposed to be.”

The fallout eventually led to the 2009 formation of the Anglican Church in North America. This explains why so many Southern Baptists who are thoughtful yet conservative, biblical yet not fundamentalist, open to diversity but not full inclusion, easily find a home in the U.S. version of the Anglican Church. One irony is that 30 years ago, during the last breakup of the SBC, ordained women and more liberal Southern Baptists sought refuge in the Episcopal Church before it birthed the Anglican Church through its own schism.

The Anglican Church drew me in from my Baptist heritage because it acknowledged my exile and gave me space to move. While I was there, it gave me a taste in the particular for what is true everywhere. But ultimately, it allowed harmful voices within its walls to speak to my children and built walls for women and LGBTQ people that I believed needed to be knocked down.

My Baptist-to-Anglican journey may be different than others. And as the rest of my life unfolds, I may not know all the particular ways I will experience community. But at each stage of my Baptist and Anglican journeys, I have experienced and cultivated a beauty that eventually expands me beyond walls and makes my exile my home.

Rick Pidcock is a freelance writer based in South Carolina. He is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com

Related articles:

For Baptists-turned-Episcopalians, Anglican disagreement feels familiar

Oprah’s interview with Meghan and Harry offers a lesson on when the ‘institution’ is the church | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

This article was made possible by generous gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.