There is a balm in Gilead,

To make the wounded whole.

There is a balm in Gilead,

To heal the sin-sick soul.

Healing is a word saturating our culture from the media promoting products to heal or relieve a myriad of physical ills to pleas from pulpits, people and politicians for healing schisms in our society.

Although we are in the midst of societal upheaval and a catastrophic pandemic, our yearning for healing is nothing new in human history. With the prophet Jeremiah we ask, “Is there no balm in Gilead; is there no physician there?” (Jeremiah 8:22).

Beverly Howard

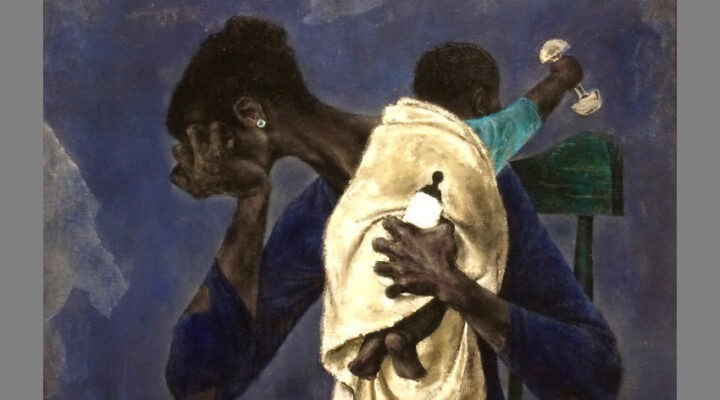

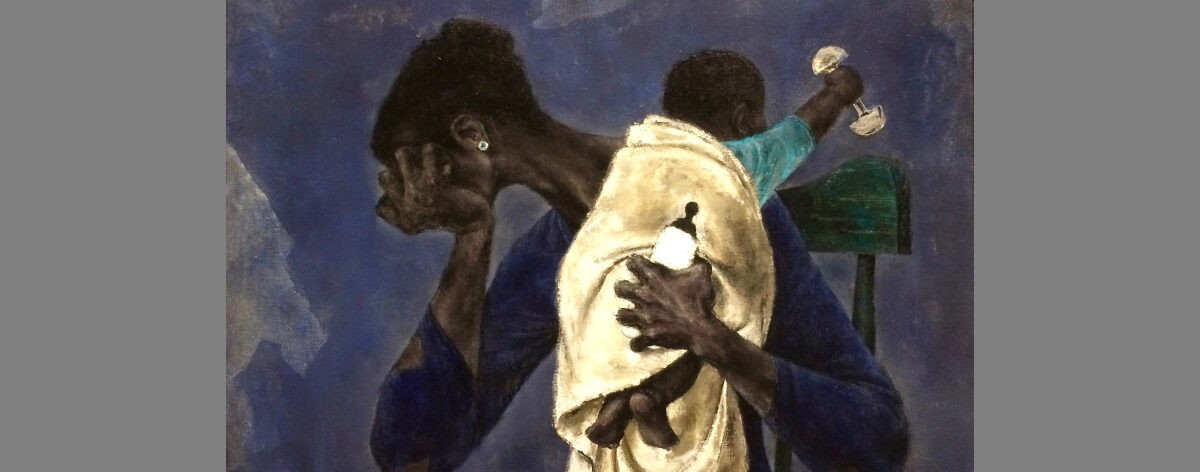

The anonymous creators of the beloved African American spiritual There Is A Balm in Gilead identified with the struggles, oppression and desperation of Old Testament forebears in faith, creating a song of hope, healing and restoration.

Theologian Howard Thurman sets Jeremiah’s question in context in his book Deep River and The Negro Spiritual Speaks of Life and Death.

The prophet (Jeremiah) has come to a “Dead Sea” place in his life. Not only is he discouraged over the external events in the life of Israel, but he is also spiritually depressed and tortured. As a wounded animal he cried out, “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is no physician there?” It is not a question of fact that he is raising — it is not directed to any particular person for an answer. It is not addressed to either God or Israel, but rather it is a question raised by Jeremiah’s entire life. He is searching his own soul. He is stripped to the literal substance of himself and is turned back on himself for an answer. Jeremiah is saying actually, “There must be a balm in Gilead; it cannot be that there is no balm in Gilead.” The relentless winnowing of his own bitter experience has laid bare his soul to the end that he is brought face to face with the very ground and core of his own faith.

Thurman further interprets the Scripture’s transformation in the spiritual:

The slave caught the mood of this spiritual dilemma and with it did an amazing thing. He straightened the question mark in Jeremiah’s sentence into an exclamation point: “There is a balm in Gilead!” Here is a note of creative triumph.

The Old Testament region of Gilead was known for its physicians and as the source of an ointment (made from balsam) used for healing purposes. Theologians have long viewed the balm in Gilead as a metaphor for Christ, the Great Physician.

“Theologians have long viewed the balm in Gilead as a metaphor for Christ, the Great Physician.”

The idea of Jesus as healer of “the sin-sick soul” was popular with 18th century hymnwriters such as John Newton (1725–1807) who penned the five-stanza hymn How Lost Was My Condition. The opening of the first stanza reads:

How lost was my condition,

Till Jesus made me whole,

There is but one Physician

Can cure a sin-sick soul.

In subsequent stanzas Newton identifies humanity’s sinfulness as a pervasive illness, plaguing the sin-sick soul. How does the great Physician heal? Through grace, he gives sight and faith to see the dying and risen Jesus.

A variant of the spiritual’s refrain “there is a balm in Gilead” first appeared as text only in The Revivalist (1853), compiled by Washington Glass as a sundry selection of hymns and spiritual songs for use in revivals, meetings and private devotions. Titled The Sinner’s Cure, Glass appropriated Newton’s text (now divided into 10 stanzas) and attached this refrain to be sung following each stanza:

There is a balm in Gilead,

To make the wounded whole;

There’s power enough in heaven,

To cure a sin-sick soul.

This particular marriage of Newton’s text with the anonymous refrain appeared in numerous 19th century collections.

“Spirituals, by nature, are contextual, meaning stanzas are created or omitted according to the needs of the community.”

Spirituals, by nature, are contextual, meaning stanzas are created or omitted according to the needs of the community. The music was first published with the three standard stanzas sung today in Folk Songs of the American Negro (1907), edited by brothers Frederick Jerome Work (1878–1942) and John Wesley Work II (1872–1925). In compiling Folk Songs of the American Negro, Work II did not include any of the stanzas from the Newton/Glass version. Instead, Work II’s stanzas focus on the singer’s experience of discouragement countered by the hope and restoration offered by the Holy Spirit.

This spiritual’s soothing balm is revered by congregations and is popular with soloists and ensembles. It reminds us that while enduring our most desolate “Dead Sea” places in life, we can straighten Jeremiah’s question mark into an exclamation point with Christ’s promise of healing and wholeness.

Beverly A. Howard lives in Fort Worth, Texas. She is a retired university music professor, former editor of The Hymn: A Journal of Congregational Song, and member of hymnal committees that prepared Glory to God: The Presbyterian Hymnal and Celebrating Grace: Hymnal for Baptist Worship. She is a collaborating author for the forthcoming hymnology textbook Sing with Understanding: An Introduction to the Theology of Christian Congregational Song with Martin V. Clarke, Geoffrey Moore and C. Michael Hawn.

Related articles:

‘Freedom songs’ make a reprise during this year of protests

Rediscovering the songs of lament would wake us up | Opinion by Greg Jarrell

Is there a balm in singing the spirituals, and if so, who should sing them? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock