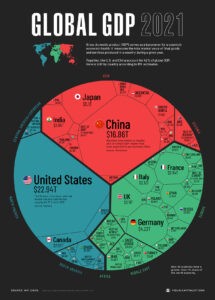

Just before Christmas, Visual Capitalist released one of its signature infographics capturing the $94 trillion world economy in a single frame. It’s a stunning image, insofar as Voronoi diagrams can be stunning, in no small part because the numbers are simply mindboggling — $94 trillion.

Perhaps the most impactful aspect of the graphic is seeing the gross domestic products of the world’s two economic superpowers, the United States and China, in context. These two countries alone account for more than 40% of the world’s total economic value.

However, what I find most fascinating about this visualization is what it reveals about how we Americans see and understand the world. This infographic is essentially what a flat earth looks like because GDP is such a very one-dimensional reference point.

However, what I find most fascinating about this visualization is what it reveals about how we Americans see and understand the world. This infographic is essentially what a flat earth looks like because GDP is such a very one-dimensional reference point.

Along with the stock market, GDP has become synonymous with the American economy. U.S. economists and news outlets obsess over it. The trouble with this obsession is that GDP never was intended to function as a gauge for economic health.

The economists who formulated the GDP during the later stages of the Great Depression and the onset of the Second World War in fact warned against lionizing GDP (or GNP as it was known at the time). That’s because GDP is simply a way to quantify economic activity.

GDP puts a dollar amount on a country’s economic output — the total value of goods and services a country produces inside its borders within a particular timeframe. GDP tells us nothing about the quality of life generated by that activity or whether the output is sustainable.

What kind of jobs is the economy creating? How equitable is the distribution of all this generated wealth? Can the nation’s people satisfy their basic wants and needs? These are all questions outside the scope of GDP.

As a result, a number of economists and world leaders have long advocated for replacing the GDP with another, more comprehensive measure that emphasizes the results of economic activity over the scale of it.

In the 1990s, the United Nations created a Human Development Index as a counterweight to GDP, combining data for life expectancy, education and standards of living to create a metric for economic progress as distinct from economic growth.

More recently, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, to which the United States belongs, began issuing biennial “How’s Life?” reports. These reports assess levels of well-being among the residents of the 38 OECD member countries based on a set of 80 indicators spread across 11 essential topics, including health care, safety, income distribution, job satisfaction, environmental quality, social connectivity and civic engagement.

“GDP tells us nothing about the quality of life generated by that activity or whether the output is sustainable.”

Despite these advancements, GDP persists, especially in the United States. Habit and convenience are surely two reasons why. When compared to the complexities of conducting a well-being assessment, calculating GDP is relatively easy. Assigning a value to the total number of cars General Motors produced in 2020 can be done in a matter of minutes with the right data set and a spreadsheet. Appraising the quality of life for the people of Detroit requires a great deal more than high school math and factory figures.

I would wager a third reason for our continuing reliance on GDP is national pride. America has possessed the world’s largest economy since the dawn of the 20th century. Ranking the nations of the world based on GDP thus consistently puts us on top.

When the standard of measurement changes, so does our relative position within the pecking order. For example, in the latest OCED index, the United States places 10th overall. In the United Nations’ HDI, America ranks 17th. Adopting either of these alternative assessments would make it more difficult to vaunt the USA as “the greatest country on earth.”

This critique isn’t to suggest there is anything wrong with calculating or reporting on the gross domestic product. GDP is a helpful tool for analyzing growth and contraction, spending patterns, inflation and other pertinent economic fluctuations. GDP isn’t bad; it simply isn’t sufficient.

“What we measure is what we manage, and when GDP occupies our metrics, we promote economic growth rather than economic health.”

What we measure is what we manage, and when GDP dominates our metrics, we promote economic growth rather than economic health. Such a skewed focus perpetuates a lopsided socioeconomic environment in which a select few reap the nation’s bounty while the majority struggle simply to make ends meet. That’s because a GDP mindset only prompts us to ask, “How many jobs were created in the last quarter?” not “How many jobs created in the last quarter offered the kinds of pay and benefits people need to flourish?”

Economic measurement tools may seem dull and even trivial, but they have theological as well as political implications. If we strive to love our neighbors as ourselves, the well-being of our neighbors should matter to us — and well-being isn’t much of a national priority at the moment.

If we want to see meaningful change, we need to start asking tougher questions about our economy and insist that our political and corporate leaders do the same. Adopting a more comprehensive economic metric in addition to, if not in place of, GDP is a good first step.

That is what a handful of other countries have done. Great Britain began keeping statistics on personal well-being in 2011. Bhutan, a tiny country in the Himalayas, famously began calculating and promoting Gross National Happiness as far back as the 1970s. Given that “the pursuit of happiness” is one of America’s founding principles, that doesn’t seem like a far-fetched concept to apply here.

What we measure is what we manage — and ultimately what we value. I wonder what might happen if The Virtual Capitalist started producing a Voronoi diagram capturing Gross National Happiness?

Todd Thomason

Todd Thomason is a gospel minister and justice advocate who has pastored churches in Virginia, Maryland, and Canada. He holds a doctor of ministry degree from the Candler School of Theology at Emory University and a master of divinity degree from the McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University. In addition to Baptist News Global, Todd writes regularly at viaexmachina.com. Follow him on Twitter @btoddthomason and Facebook @viaexmachina.

This article was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.

Related articles:

The U.S. wealth gap presents both a political challenge and a spiritual problem | Analysis by Todd Thomason

Social liberalism grows while economic conservatism still dominates

The Bible demands economic justice | Opinion by Miguel de la Torre

America’s economy urgently needs more immigrant labor, experts explain