A few years back, as I wandered across a broad hill overlooking Washington, D.C., I discovered a monument, the statue of a woman atop a 32-foot decorated pedestal rising above the untold thousands of gravestones in Arlington National Cemetery.

I didn’t at first know what it stood for or who it memorialized. There are a lot of monuments at Arlington.

Cherry trees bloom in Jackson Circle around the Confederate Monument in Section 16 of Arlington National Cemetery, April 7, 2015, in Arlington, Va. The Confederate Monument was unveiled June 4, 1914, according to the ANC website. (Arlington National Cemetery photo by Rachel Larue)

But as I walked closer, the memorial began to reveal its true nature. Among the bronze figures on the monument’s frieze are a male slave following his master into battle. A slave “Mammy” holding up an infant for a Confederate officer to kiss before he departs. And at the base of the monument, this inscription, “To Our Dead Heroes by the Daughters of the Confederacy,” and a Latin quotation, Victrix causa diis placuit sed victa Caton (“The winning side was pleasing to the gods, but the lost cause to Cato.”)

You don’t have to know Latin to recognize that this Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery is a thumb in the eye of the Union, planted at the symbolic heart of the nation’s remembrance: “We were right, and you were wrong.”

If it seems wrong to you that rebels and insurgents, people who fought to overthrow the very concept of the United States, should be memorialized in our national cemetery, that such a statue could stand in a straight line up the hill from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, then we are in agreement. But there’s more. Yes, I found this monument, visually offering hateful and hurtful myths about race, but I also found a substantial group of Confederates interred in circles around it, Rebel soldiers buried perhaps within sightlines of the headstones of Union soldiers they killed, while the whole shebang is ringed by Stonewall Jackson Circle.

Detail on the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery.

A few weeks ago, retired General Ty Seidule, former chair of the history department at West Point, current professor of history at Hamilton College and author of the book Robert E. Lee and Me, laid out for me the obvious truth about this and other remembrances of the Confederacy: “Commemoration is about our values. The statues reflect even more about the people who put them up than about the people memorialized.” He has called the Confederate Memorial at Arlington Cemetery “the cruelest monument in the country,” and written that “the statue represents all the terrible lies of the Lost Cause.”

As I trust you know, the Lost Cause is a set of white supremacist myths about the Civil War, slavery and American history and destiny. Novelist and historian Shelby Foote said in Ken Burns’ Civil War that “Lost things are always prized very highly,” and the Lost Cause is a narrative with nostalgic force, a story that defines how we think about race, justice and American identity down to our present moment.

The Lost Cause argues that the South fought well, bravely and chivalrously in the Civil War. Something essential to the American character was lost when the South surrendered. And although Foote himself acknowledges the evil of slavery (many Lost Cause proponents defend, diminish or ignore it), he seems to suggest that the Southern Way of Life was somehow worth the “stain and sin” of holding millions of humans in bondage.

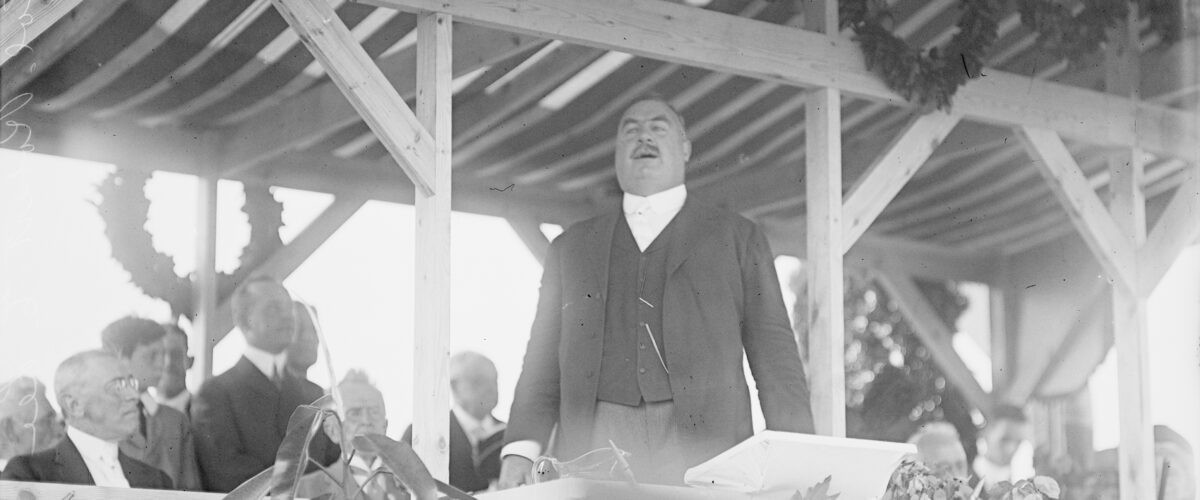

On June 4, 1917, Daughters of the Confederacy unveils the “Southern Cross” monument at Arlington National Cemetery. (Getty Images)

Textbooks in the South presented these lies for many years after Reconstruction ended. During that same hundred-year timeframe, the Daughters of the Confederacy strategically placed statues and monuments all over the country, often on public land, as part of a successful effort to win the war of memory. And today, governors and state legislators (including those in my own state of Texas) are forbidding the teaching or reading of unpleasant truths from our past that might make white students uncomfortable, promoting an ignorance that at best whitewashes the Lost Cause, and at worst, permits it to spread unchecked.

Like Gen. Seidule, I was raised in the South with these myths ringing in my ears. I know how powerful and, now, how pernicious they are. The Lost Cause justifies racial prejudice, racial violence and white ascendancy. It forestalls any possibility of reckoning with a past that is not remembered honestly. It diminishes the evils of slavery and of Jim Crow and thus makes it harder to repair the systemic evils that still diminish the lives of people of color.

A supporter of President Donald Trump carries a Confederate battle flag on the second floor of the U.S. Capitol near the entrance to the Senate after breaching security defenses Jan. 6, 2021. A portrait of abolitionist senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who was savagely beaten on the Senate floor after delivering a speech criticizing slavery in 1856, hangs above the couch. (REUTERS/Mike Theiler)

Gen. Seidule spoke to me about seeing a Confederate battle flag inside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, about how — like me — he was shattered to see this Lost Cause myth continuing to reverberate in our national life. The Confederate battle flag, he said, “has now the same meaning that it did then,” that white Southern men should rule, and that Black people belong in a perpetual state of subservience to them.

The Lost Cause is a seductive myth of identity because it reshapes defeat into moral victory. It claims a descent from nobility even to poor whites who are victimized themselves. But it is a myth that rejects the reality that we are all children of God, and it stands at cross purposes to the scriptural calls for justice and fairness.

“The Lost Cause is a seductive myth of identity because it reshapes defeat into moral victory.”

Monuments like the one at Arlington are coming down all over the country, but taking down a plaque or statue does not erase the ideology that drove it to be placed in the first place. That will require the efforts of all those people Dr. King called people of good will, all those willing to acknowledge that, as James Baldwin used to say, no evil can be remedied until it is faced, to take on this hate and to replace it with love and justice.

It will take faith, courage, tenacity and hard conversations, and it will not happen overnight, but it is time and past time for us to take the Lost Cause off its pedestal and cart it away to storage.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and canon theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

A tale of two cities: Telling the truth about race | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

At the intersection of Monument(s) and Avenue(s), a new vision rises | Analysis by Craig Martin