When the Nazis invaded Holland in 1940, Gerrit tenZythoff was 17 years old and leading the sort of life that was common for teenage boys even then — a life filled with schoolwork and sports and good friends. And then his life began to change.

First the authorities confiscated the textbooks written by Jews. Then his Jewish teachers and classmates disappeared, the family doctor — also a Jew — died by suicide, and the local butcher who had served the tenZythoff family for so many years — another Jew — was beaten to death.

In the midst of kothese horrors, Gerrit’s family — like so many other Dutch Christian families — sheltered Jews in their home.

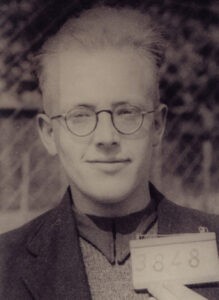

Gerrit tenZythoff as a prisoner.

In 1943, when Gerrit refused to sign a loyalty oath to the German regime, the Nazis imprisoned him in Berlin where, through unthinkable acts of torture, they sought to extort from him the names and addresses of people in Hoog-Keppel — the village where the tenZythoff family had lived for many years — who were sheltering Jews. Gerrit adamantly refused.

Then, in 1945, when Allied planes scored a direct hit on the prison where Gerrit was incarcerated, he walked free and made his way back to his native Holland.

When he reached the family home, he found there several children he did not know. When his mother explained who the children were, Gerrit stormed out of the house, slamming the back door as he went. “They’re Nazis!” he screamed. “I won’t stay under the same roof with those bastards!”

“Yes, Gerrit” his mother replied. “They are children of Nazis. But we are Christians, and we will stand with those who suffer.”

I was privileged to work under Gerrit tenZythoff from 1977 through 1982, just a few of the years when he chaired the department of religious studies at Southwest Missouri State University. And I have thought of Gerrit often — and the words his mother spoke — as I have observed the racial crisis of our time and the reluctance of so many Americans — including many Christians — to stand with oppressed and marginalized people.

It is almost as if the horrors of slavery, lynching and Jim Crow segregation were not enough. Now, today, when Black people want their painful story of suffering both told and heard, many Christians close their hearts, their minds and their ears.

“Today, when Black people want their painful story of suffering both told and heard, many Christians close their hearts, their minds and their ears.”

“We don’t want to hear that story,” they seem to say. “It might make us feel guilty. So tell it to yourselves if you want, but keep it out of our schools and our churches. For the story we wish to hear is the story of goodness and innocence. Yes, please, keep your story to yourself.”

And as I read about school boards that ban certain books that tell the story of Blackness in American life, or various government agencies that make it unlawful to teach about racial strife, or Christians who refuse to acknowledge the truths of the “1619 Project” or the insights offered by Critical Race Theory, I not only think about Mrs. tenZythoff. I also think of Toni Morrison.

In her Nobel Lecture of 1993, Morrison spoke bluntly of what she called “official language” — what in our context we might call the “official story” — a story of an innocent, white America that has no room for any story but the one that gives us comfort and assures us we are innocent after all.

Gerrit tenZythoff five days before his death in 2001.

That sort of language — that sort of story — she writes, “actively thwarts the intellect, stalls conscience, suppresses human potential. Unreceptive to interrogation, it cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences.”

She describes that sort of language — that sort of story — as “oppressive language (which) does more than represent violence; it is violence. … It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind.”

The fact is simply this: To take away a people’s story, to ban its telling and its hearing, is just one more way to keep people in subjection. For without a story, we cannot live. That is why Morrison insists that “official language” — the official story that excludes those who do not fit its categories — “does more than represent violence; it is violence.”

Gerrit tenZythoff’s mother reminds me that as Christians, we have an obligation to stand with oppressed and marginalized people, no matter who they are. The tenZythoff family, of course, was only responding to Jesus’ charge to welcome the stranger and to care for the least of these. But the first step in living out that vision is hearing another person’s story. That is the least we can do.

Richard T. Hughes

Richard T. Hughes serves as scholar in residence at the Center for Christianity and Scholarship and College of Bible and Ministry of Lipscomb University in Nashville. He is the author of Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning.

Editor’s note: Learn more by accessing the text of oral interviews conducted with Gerrit tenZythoff.

Related articles:

The Maus saga: A case study of our present crises | Opinion by Bill Leonard

It’s time to stop the insanity that is killing public education | Opinion by Mark Wingfield