United Methodist leaders are struggling to get accurate information to pastors and members as the denomination hurtles toward a de facto division May 1. One of the UMC’s regional units has voted to join a new traditionalist church when it launches, while an undetermined number of local congregations appear poised to leave as well.

Transitional leaders of the Global Methodist Church, a breakaway denomination created by the traditionalist Wesleyan Covenant Association, set May 1 as its launch date after the UMC’s General Commission on the General Conference postponed the denomination’s top legislative assembly, usually held every four years, for a third time. While the ongoing coronavirus pandemic played a major role in the delay, the key factor in the postponement to 2024 was the difficulty of obtaining travel visas for international delegates.

General Conference, which had been scheduled for late summer this year, is the body slated to vote on several proposals to allow United Methodists to split — or to splinter, as church historian William B. Lawrence asserted in a recent commentary for United Methodist News Service. Paramount among the proposals has been an independently negotiated agreement known as the Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, a pact that among other things would provide $25 million in seed money over four years for a new traditionalist denomination. Without a vote on the Protocol, there is no official agreement on whether or how to divide The United Methodist Church.

The 12-million-member worldwide denomination was rocked April 7 when news came that the Bulgaria-Romania Conference had defied church policy and voted to join the GMC May 1.

Thus the 12-million-member worldwide denomination was rocked April 7 when news came that the Bulgaria-Romania Conference had defied church policy and voted to join the GMC May 1. Bishop Patrick Streiff, Bulgaria-Romania Conference supervisor, had ruled the proposal out of order when it came up for consideration April 1, whereupon dissidents convened in a separate location and voted themselves out of the UMC. Since the Bulgarian church has incorporated itself with a new name and leadership, the action may be legal under Bulgarian secular law but it’s unprecedented according to church policy.

The Bulgaria-Romania vote also jumped the gun on a pending decision by the United Methodist Judicial Council, its “high court,” over whether annual conferences, considered the basic unit of the denomination, have the right to withdraw in the same way that local congregations do. The Council of Bishops requested a ruling from the Judicial Council, which isn’t expected until after the new Global Methodist Church launches.

The process for leaving the UMC is known as “disaffiliation” and is described in sections of the United Methodist Book of Discipline, the collection of church laws and policies. Key to disaffiliation is a section called Paragraph 2553, which outlines the process, timeline and financial obligations of a church seeking to leave the UMC with its real and personal property. The UMC operates with what’s known as a “trust clause,” meaning all local property is held “in trust” for its annual conference, which typically provides start-up funding for congregations.

Trouble is, not everyone sees the path to disaffiliation in the same light, and therein lies the looming battle. Church leaders through the United Methodist hierarchy are developing communications plans intended to cut through the fog of rhetoric and recrimination over how the impending division has come about. In short, most congregations won’t be affected unless they want to leave the UMC.

Most congregations won’t be affected unless they want to leave the UMC.

For example, the Arkansas Annual (regional) Conference has published a toolkit for its pastors and lay leaders to use in communicating what’s coming. The toolkit includes an introductory video featuring Arkansas Bishop Gary E. Mueller, a set of slides with a script, a list of frequently asked questions, and a video of a closing prayer by the conference lay leader, Kathy Conely. The conference is scheduled to meet in annual session June 1-5, which gives leaders about a month to communicate what’s happening.

Since late March, the Florida Annual Conference has held a series of district meetings on the theme of “the continuing United Methodist Church” that describes the effects of the General Conference delay, including the Global Methodist Church. Florida has been a hotbed of Wesleyan Covenant Association campaigning for the new traditionalist denomination. The Florida WCA chapter has been criticized for holding its meetings in United Methodist churches while barring entrance by anyone not supporting the new church.

Social media debates over the impact of the official disaffiliation policy also have muddied the waters as to what might happen if a local church chooses to depart.

Chris Ritter, “directing pastor” of the multisite Geneseo First UMC in Geneseo, Ill., kicked off the most recent kerfuffle with a blog post titled “The Deficiencies of Disaffiliation.” He criticized the the 2019 legislative process that brought Paragraph 2553 to the fore. Ritter’s post led to a riposte from a Kansas progressive pastor, David Livingston, who refuted Ritter based on his own re-watching of the video record of General Conference votes. Finally, a traditionalist pastor from Indiana, Beth Ann Cook, rebuked Livingston’s version of the 2019 events and added a list of the varied ways that disaffiliation is being pursued in U.S. annual conferences as evidence that United Methodist bishops are manipulating procedures to punish departing congregations financially.

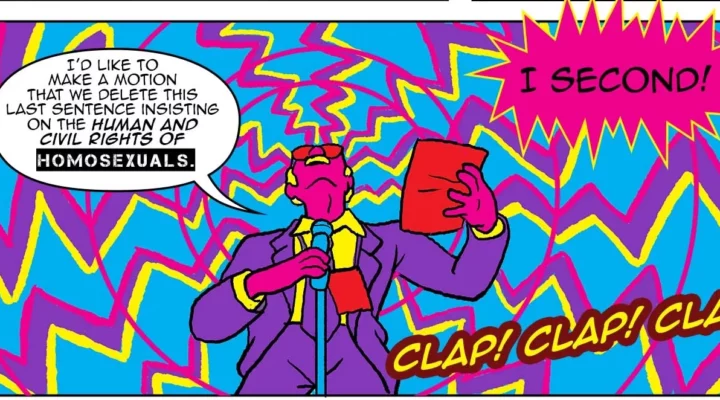

What’s behind all this United Methodist turmoil? For some dissidents, the presenting issue is whether the UMC should abandon its 50-year-old prohibition against homosexual practice as “incompatible with Christian teaching.” United Methodist ordained deacon Charlie Baber, creator of the popular “Wesley Bros” cartoon series, recently published “A History of Incompatibility” in two parts to sketch out the rocky path toward this break-up.

Much like right-leaning politicians embracing authoritarianism, United Methodist traditionalists have been pushing against the UMC’s “big tent” identity since the denomination formed in 1968.

However, longtime observers note that much like right-leaning politicians embracing authoritarianism, United Methodist traditionalists have been pushing against the UMC’s “big tent” identity since the denomination formed in 1968. In much the same way that conservative pundits chastise concepts such as “woke” culture and Critical Race Theory, traditionalists have tried to constrain the UMC’s theological method known as the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, a term coined by the late theologian Albert C. Outler to describe how John Wesley interpreted Scripture using tradition, experience and reason. Thus, traditionalist theology often is criticized by progressives as practically Calvinist in nature, with an emphasis on inflexible doctrines and a lack of theological discourse. With a proclivity for church organization more in line with congregational polity than United Methodism’s trademark “connectionalism,” traditionalists also have chafed particularly at the power wielded by bishops.

Church leaders who have analyzed the GMC’s Transitional Book of Doctrine and Discipline say it addresses both issues sternly, with congregations and members subject to automatic dismissal if they transgress church doctrine, and bishops limited to terms and scrutinized intently. In particular, analysts from the Western Pennsylvania Annual Conference said they were most concerned about the GMC’s effect on local congregations and on United Methodism’s longtime goals of racial, ethnic, economic and gender inclusion.

“In the GMC, churches can say they don’t want a woman, a Black, a Korean; they only want a straight white male with a wife and children,” pastor B.T. Gilligan told United Methodist Insight in August 2021. “Gifted pastors won’t get appointed, and churches that need and should get good leadership aren’t going to get it. Then a downward spiral starts, and if a church doesn’t perform to the level the GMC wants, it’s out.”

See more of the Wesley Bros graphic educational series here.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

Related articles:

Here’s what you need to know about why United Methodists now appear headed for a nasty divorce

Now there appear to be three paths for once-united Methodists

Top-down schism plans ignore local United Methodist churches’ new reality

New denomination declares ‘liberation’ from United Methodist Church