Adopting some of the tactics of the Religious Right may be instrumental in opposing the movement’s assault on democracy and faith freedom, said Katherine Stewart, an investigative journalist and author who tracks Christian nationalism in the U.S. and globally.

“They operate in unity when necessary. They get people focused on turning out the vote,” Stewart said during an online interview hosted May 10 by Union Theological Seminary in New York.

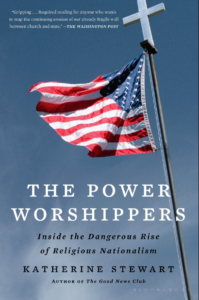

“They offer so many paths to engagement. It doesn’t matter how young you are, how old you are or if you’re disabled. It doesn’t matter. We’ll find you if you want to be active in engaging the vote, we will get you involved. Those tools are available to all of us,” said Stewart, author of The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism.

Katherine Stewart

Christian nationalist leaders have used those and other methods to mobilize a minority of Americans into a powerful voting bloc that “punches above their weight,” she said, advising that Democrats and others should take heed by bringing at least one person to the polls who didn’t previously vote or who may have once supported conservative candidates.

But no doubt many of the movement’s tactics should not be imitated, including the manipulation and misleading of voters in the pursuit of racist and authoritarian control, she added. “They’re not afraid to lie. They’re not encumbered by loyalty to truth or fact.”

During an interview conducted by Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of Union’s Episcopal Divinity School, Stewart connected the dots between the pro-slavery origins of religious nationalism and its later use of the abortion issue to motivate support for a modern political movement bent on creating a Christian nation based on a narrow, conservative reading of the Bible.

Critics of the movement often have overlooked the sophisticated political machine constructed by religious conservatives to pursue their vision of religious liberty defined by white Christian dominance, she said. “We are seeing the consequences of decades of planning by Religious Right legal strategists to stack the courts with ideologues. That’s one of the features of the Christian nationalist movement which consists of right-wing Christian advocacy groups, policy groups, legislative initiatives, networking organizations and the like.”

In addition to patiently and persistently promoting like-minded judges, Christian nationalist leaders have been “picking the right cases and bringing them to the right courts in order to form the building blocks of decisions that are going to degrade the separation of church and state and bring about their vision of an America with laws based on their understanding of religion,” Stewart said.

Abortion became another tool of the movement with the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling. Opposition to that ruling played into the hands of arch conservatives like Phyllis Schlafly, Paul Weyrich and Richard Viguerie, among other founders of what was then called the New Right movement, who were searching for a cause to cover other political ambitions.

“We are seeing the consequences of decades of planning by Religious Right legal strategists to stack the courts with ideologues.”

“The thing that really got them up in the morning, the thing that really offended them, was the fact that the IRS was starting to look at the tax-exempt status of these (private) segregated schools, many of which were run by Bob Jones, (Jerry) Falwell and other Southern pastors,” Stewart said. “They knew that ‘stop the tax on segregation’ wasn’t going to be an effective rallying cry for them.”

The movement considered, and discarded, other hot-button issues such as school prayer and the proposed Equal Rights Amendment as their central focus, she continued. “When they got to abortion it was like a lightbulb went off. It was an identity issue that they could use to channel people’s anxieties around identity and family and sexuality. They thought that could work. So, over time they purged pro-choice voices from the Republican party.”

The recent leak of a U.S. Supreme Court draft decision that would overturn Roe v. Wade demonstrates that the movement’s patient work is paying off for organizers, Stewart claimed. “This sort of pro-life religion that we have now is used by the Republican Party to distinguish between insiders and outsiders, the pure versus the impure, the saved versus the damned. It’s a modern creation and it was created for political purposes.”

And yet the underlying race issue that motivated early proponents of Christian nationalism remains at work in the movement, she said. “Christian nationalism as a political movement is also driving support for politicians who engage in race-based gerrymandering and voter suppression that disproportionately affects people of color and others in Democratic-leaning districts. They’re engaging in race-baiting around (Critical Race Theory) and book banning in public schools and libraries and by writers of color.”

And yet the underlying race issue that motivated early proponents of Christian nationalism remains at work in the movement, she said. “Christian nationalism as a political movement is also driving support for politicians who engage in race-based gerrymandering and voter suppression that disproportionately affects people of color and others in Democratic-leaning districts. They’re engaging in race-baiting around (Critical Race Theory) and book banning in public schools and libraries and by writers of color.”

The racism inherent in the effort can be traced to 19th century Southern theologians who promoted biblical justifications for slavery and “this idea that a right-thinking elite should dominate over everyone else,” Stewart said. “There is a throughline between those ideas to the religious nationalism in America that we are seeing today.”

Christian nationalists also share an affinity with authoritarian leaders around the world who typically align themselves with like-minded religious figures. The trend explains why so many American conservatives admire Russia’s Vladimir Putin and his alliance with the Russian Orthodox Church, she said.

“They bind themselves to these ultra-conservative clerics in order to consolidate a more authoritarian form of political power and use religion to … perpetuate what are often kleptocratic, nepotistic governments. We rightly recognize these as forms of religious nationalism, and that’s certainly what we saw with Donald Trump. No one believes that this a man of faith or, if he is, it’s a matter of convenience.”

Christian nationalists also claim they want to protect religious liberty. But Stewart noted that for them, religious liberty means protecting their own beliefs and practices at the expense of others.

“In the hands of movement leaders, it’s become the idea that the people with the correct views have the right to discriminate against people who have incorrect views; that there should be privileges for approved groups in society and contempt can be directed toward other groups in society.”

Related articles:

Five takeaways from the Report on Christian Nationalism and January 6 | Opinion by Corey Fields

Interdenominational panel warns of extreme danger of Christian nationalism