Imagine going to medical school or law school and finding out once you graduate and enter your practice that you must forget at least 25% of what you learned or lose your job. Yeah, that is what it’s like for many pastors going from seminary to the church.

It’s an unspoken rule that you can’t tell your congregants everything you learned or you’ll hurt their faith and/or get fired.

Aaron Van Voorhis

I attended relatively conservative schools for both my undergraduate and graduate theological degrees (Lipscomb and Fuller). I enjoyed both of them and found them to be very similar in many ways. However, even in those relatively conservative schools, I heard things I never heard in church and knew would be dangerous to teach in such a setting:

- The shocking violence of church history.

- The imperfections of the Bible.

- The ahistorical nature of many of the Bible’s stories.

- The endless complexity of hermeneutics and the culturally contingent ways all religions develop and evolve. In other words, theology is anthropology.

Unlike many of my classmates who have gone into ministry as well, I couldn’t just ignore these things and keep my mouth shut. I had to explore them and follow them where they lead.

I remember 15 years ago being confronted by my boss, who also was senior pastor of the church where I worked, for having a copy of Richard Dawkins’ book, The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence for Evolution Reveals a Universe without Design. He saw the book on my desk and sternly asked why I was reading it. I immediately felt anxious and muttered something like, “I just want to know how the other side thinks so I can refute it.”

But that wasn’t entirely true. I was fascinated by Dawkins’ arguments and wanted to expand my understanding of the world. I no longer completely trusted evangelicalism’s version of reality and its anti-science bias. I wanted the freedom to explore and to know for myself.

“Why are churches that openly embrace doubt and unknowing, progressive theology and politics so small and scarce compared to conservative churches?”

I soon left that job and continued my studies at Fuller Seminary, where my exploration and deconstruction really took off. And yet, I discovered there that I wasn’t alone and that embracing questions, doubt and unknowing could actually be a good thing and not antithetical to Christianity. After graduating from Fuller, I founded Central Avenue Church in Glendale, Calif. Even though we’ve existed for a decade now, we’re a small community but I wouldn’t want it any other way.

This raises an interesting question: Why are churches that openly embrace doubt and unknowing, progressive theology and politics so small and scarce compared to conservative churches? If progressive churches are merely acquiescing to cultural pressures and telling people what they want to hear, as many evangelicals claim, then why are they not as prevalent and as large as conservative churches? I think the reasons are complex but mostly have to do with why people go to church and are attracted to religion in the first place.

In general, people in our culture are attracted to religion and spiritual communities that promise certainty, fulfillment and satisfaction. We are a culture of consumers, each on a quest for self-actualization and wholeness. Any product, service or religion that promises those things will sell. Likewise, any product, service or religion that doesn’t promise those things or outright denies they exist (as in my case), doesn’t sell. This is largely why conservative churches continue to “succeed” more than progressive and radical communities. Certainty sells.

“We are a culture of consumers, each on a quest for self-actualization and wholeness.”

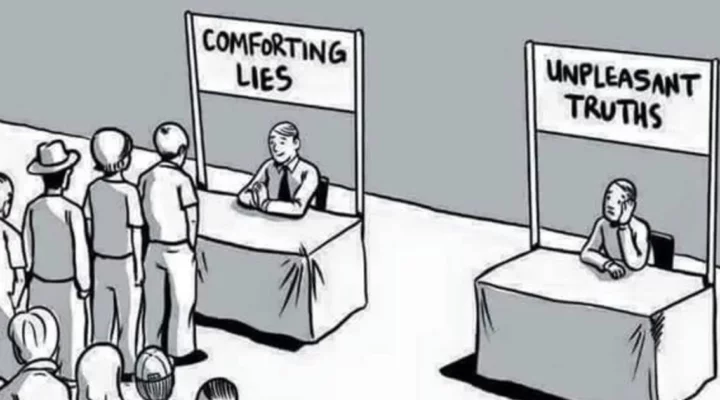

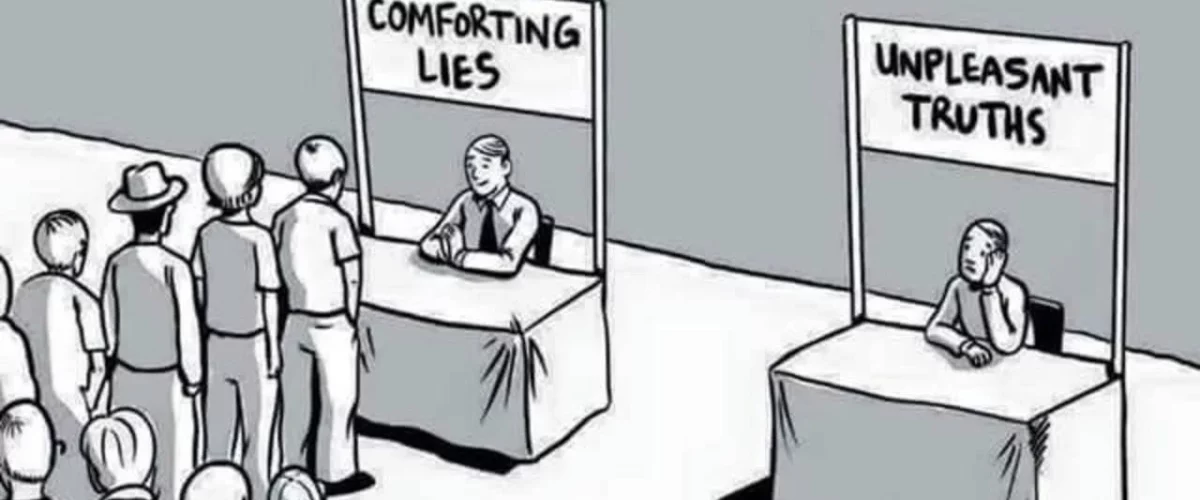

I’m reminded of a meme I once saw that showed two buildings side-by-side, each with a sign above its door. One sign said, “Comforting Lies,” and the other “Unpleasant Truths.” The building with the sign that read, “Comforting Lies” had a long line of people out the door waiting to get in. The other had only a couple.

Isn’t this always the case, especially when the buildings in question are churches? And yet, Christianity is a religion about a crucified God, which I understand as the crucifixion of certainty and the resurrection of faith — faith as a way of living in the world as Christ — faith as a way of giving ourselves completely over to love and life in the world as it really is, in all of its brokenness and uncertainties. This, to me, is Christianity now.

This article began as a post I made on Facebook and received such an enormous response that I was asked to do an expanded write-up here for BNG. It seems many of us have had similar experiences and reached similar conclusions. I am encouraged by how many people are coming out of unhealthy communities and theologies and leading or finding churches like mine. It seems the so-called “deconstruction movement” is growing. An increasing number of people are encountering ideas and information, mostly online, that does not allow them to remain silent or stay within the tight confines of orthodoxy.

As my friend and colleague Tad DeLay says, “Prohibitions on doubt shred credibility.” The church has only hurt itself by telling its leaders coming out of the academy: Forget a lot of what you learned.

Aaron Van Voorhis serves as lead pastor at Central Avenue Church in Glendale, Calif., a progressive and affirming community of mostly recovering evangelicals. He earned a bachelor of arts degree in biblical studies from Lipscomb University and a master of divinity degree from Fuller Seminary. He is the author of A Survival Guide for Heretics and writes and speaks often from a Radical Theology perspective.

Related articles:

Pastors, speak your truth while you still have time | Opinion by Jakob Topper

Moderate ministers and churches: Want to kill Church in America? Just keep doing what you’re doing | Opinion by Russ Dean

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr