In the fourth chapter of Luke, the devil led Jesus to a high place and “showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world.”

Next came the pitch: “To you I will give all this authority and their glory, for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please. If you, then, will worship me, it will all be yours.”

Like the devil, Donald Trump knows the art of the deal. As a private citizen, he was a liberal’s liberal: pro-choice, pro-gun control, pro-universal health care. But to win the presidency, Trump needed to plug in to somebody else’s vision. White evangelicals and conservative Catholics shared a common vision. What’s more, they were desperate. And they knew what they wanted: Complete control of the Supreme Court.

So Trump summoned these conservative religionists to the observation deck of Manhattan’s Trump Tower and, pointing over the horizon, showed them the Supreme Court building. “To you I will give all this authority and glory,” he said. “I would like you to do me a favor, though. If I give you the court, you will never question the way I do business. Look away, make excuses, change the subject — whatever you have to do. But I must have a free rein.”

Paradise lost

John Milton’s devil is nuanced, introspective and philosophical; that’s why he steals the show in Paradise Lost. Trump possesses none of these qualities, but there is more than a dash of the devilish in Trump’s politics. Milton’s devil crows that all can never be lost so long as he retains an “unconquerable will, and study of revenge, immortal hate, and the courage never to submit or yield.”

“There is more than a dash of the devilish in Trump’s politics.”

This is how Trump sees himself. His thirst for revenge, his implacable hatred for all who oppose him, and his refusal ever to admit defeat make him irresistible to his chosen constituency. Trump will “never submit or yield,” which is why, even after Jan. 6, the Republican base refuses to cut him loose. Where else could they find such audacity?

Not with Kevin McCarthy, Ted Cruz, Steve Scalise, Jim Jordan or Margorie Taylor Greene.

This species of sycophantic politician reminds me of a classic scene from The West Wing in which the principled Toby Ziegler dresses down a polls-over-principle operative named Al Kiefer.

“I just figured out who you are,” Ziegler says.

“You’re going to say ‘Satan,” Kiefer smirks.

“No,” Ziegler replies calmly, “you’re not Satan. You’re the guy who runs into the 7-11 to buy a pack of cigarettes for Satan.”

That’s the way I see the likes of Cruz and McCarthy, soulless men standing in the checkout line with a pack of Camels. They have become irrelevant. Nothing matters except the deal between Trump and his religious base.

Trump promised he would “make American great again.” Liberals like to ask when America was ever great. Are we talking about Jim Crow America, or the years preceding the Emancipation Proclamation? Trump doesn’t care what his catchphrase means. He just knows it fires up a crowd. But to his religious base, the MAGA mantra reveals a hankering after John Cotton’s America.

John Cotton’s vision

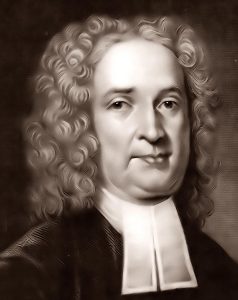

John Cotton

In 1633, John Cotton fled his native England to escape religious persecution. Thousands of his co-religionists did the same. Cotton was a Puritan, a group that Charles I, England’s reigning monarch, had learned to despise. The Cambridge-educated, multi-lingual Cotton quickly established himself as one of New England’s leading preachers and theologians.

Like most Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Cotton remained loyal to the Church of England. The Church had been corrupted, he admitted, but England was still God’s chosen people, and England’s king was still his sovereign. By withdrawing to America, Cotton hoped to purify a church that was intent on silencing him.

Like all good Puritans, Cotton hated Roman Catholics. Ever since the fourth century, when the church linked arms with Constantine’s Roman Empire, she had forgotten her true calling. But the Protestant Reformation had given true believers a path back to New Testament purity. By renouncing the pope and cleaving to the holy Scriptures, Cotton believed, the religion of Jesus could be rescued. Massachusetts Bay was to be, in the words of Cotton’s friend John Winthrop, “a city set upon a hill,” a beacon of light for a dark world.

“Good Puritan that he was, Cotton claimed the entire biblical narrative as his own.”

Good Puritan that he was, Cotton claimed the entire biblical narrative as his own.

God’s covenant relationship with the kings of Israel had transferred to the church.

When Azariah ordered king Asa to purify Israel of idolatry and false belief, the prophet was giving the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay their marching orders.

The public officials of New England were tasked with enforcing true doctrine and godly behavior and, clearly, none but regenerate Christians were up to that task.

For Puritans, prophetic books like Daniel and Revelation foretold the history of the world from creation to the second coming of Jesus Christ (which was just over the horizon). Every thought and deed, Cotton believed, must be captive to Scripture. Those who strayed from the paths of holy writ, therefore, must be disciplined by Christian magistrates who answered to the church. There could be no line between church and state.

If he suddenly appeared in our world, John Cotton would be horrified to learn that all six conservative Supreme Court justices are Roman Catholics but, after recovering from his shock, the Puritan divine would find his way in MAGA world. It is, arguably, the closest thing to his vision currently on offer.

Roger Williams’ vision

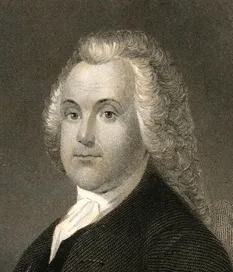

John Cotton’s vision for America was challenged by his nemesis, Roger Williams. During his lifetime, Williams was a man with nowhere to lay his head. His books were ceremonially burned throughout England and New England. But when the United States of America drew up a Constitution 104 years after Williams died, it was his vision, not Cotton’s, that won the day.

“When the United States of America drew up a Constitution 104 years after Williams died, it was his vision, not Cotton’s, that won the day.”

The framers of the Constitution took their ideas from John Locke, not Roger Williams. But, as Winthrop Hudson once observed, on the issue of religious freedom, “it is impossible to discover a single significant difference” between Williams and the call to religious freedom “later advanced by Locke.”

American liberals, religious and secular, long have claimed Roger Williams as their own. The father of Rhode Island called for unqualified religious toleration. Unlike Locke, he didn’t draw the line at atheists and Roman Catholics.

Famously, Williams didn’t care if civil magistrates were Muslims, Catholics, Quakers or adherents of no religion at all, so long as they were qualified and uncorruptible.

Roger Williams

Williams declared the king of England had no legitimate claim to American territory since it was all owned by Native Americans.

But Williams was a child of his age. His did not see women the equals of men, nor did he deem all religions to be of equal worth. If he was radical, it was because he pressed the Calvinism he absorbed at the University of Cambridge to its logical conclusions.

The doctrine of total depravity made Williams suspicious of evangelistic preaching. The human will, he believed, could neither prick the conscience nor dispel the ancient taint of sin. Salvation was the gracious gift of a sovereign God. Therefore, attempts to coerce religious conversion or doctrinal orthodoxy were futile. When imposed by the sword, religion was rank hypocrisy that flooded the world with unregenerate pretenders.

Williams was determined to keep the “garden of the church” unsullied by “the wilderness of the world.” Civil magistrates might be charged with enforcing the “second table of the law” (laws applicable to human society) but must not meddle with the first table (which touched on God’s dealings with humanity).

To Williams, the idea of a Supreme Court enforcing religion values would have been anathema.

Christianity, Williams taught, had fallen “asleep in Constantine’s bosom, and in the laps and bosoms of those Emperors professing the name of Christ.” Although well-intentioned, Constantine had done far more damage to the church than the predatory Nero.

As a consequence, Williams reasoned, the Apostolic authority of the early church had been severed and the church had surrendered its mandate to preach in Jesus’ name. The Church of England was far too broken to be reformed and must be abandoned. The best anyone could do was to humbly seek after the truth in anticipation of the Second Advent. To his mind, Christendom was a tool of Antichrist.

God’s covenant with Israel, Williams argued, was unique and unrepeatable. While his fellow Puritans emphasized the righteous, idol-smashing kings of Israel, Williams pointed out that, for the majority of her history, Israel had lived under the thumb of foreign unbelievers. Few of Israel’s kings served as positive role models, while foreign princes like Artaxerxes and Cyrus, although disdainful of Israel’s religion, treated God’s elect with honor and restraint.

Williams hoped God soon would provide a way out of the church’s dilemma, but until that happened, New Testament Christianity was impossible. Anything short of a new covenant, unambiguously initiated by God, was a deal with the devil.

Which is why, in the winter of 1635, Williams was cast out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony into the “howling wilderness.” After tramping for days through forests thick with knee-deep snow, Williams survived through the ministrations of Wampanoag and Narragansett Indians.

When spring came, Williams nursed himself back to health, purchased land from local sachems (tribal leaders), and founded what would become Providence, Rhode Island.

Williams returned to England in 1643 to negotiate a charter for his Rhode Island colony. There, he published a rambling, prolix treatise, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience.

Cotton soon gave his response, The Bloody Tenent, Washed, and made White in the Bloud of the Lambe.

Four centuries after Cotton and Williams crossed swords, the options haven’t changed.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

Antidisestablishmentarianism is attempting a coup: Don’t laugh | Opinion by Bill Leonard

On Roger Williams, freedom of conscience and its (sometimes well-intentioned) enemies | Opinion by Erich Bridges

This Supreme Court’s dangerous vision of ‘history and tradition’ | Analysis by Robert P. Jones