Roger Williams agreed with the Puritan overlords of Massachusetts Bay on most points of doctrine, but when his thinking diverged from accepted orthodoxy, he said so. Plainly and without apology.

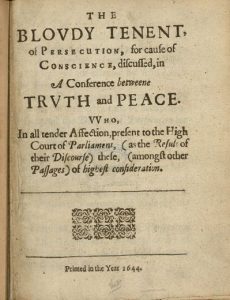

In The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, Peace and Truth are portrayed as unrequited lovers who have long been separated by religious intolerance. There can be no peace without truth, Williams says, and truth never will flourish unless men and women are allowed to live in peace. Williams found the place where truth and peace embraced, and there he made his stand.

Alan Bean

“Most precious Truth,” Peace exclaims, “you know we are both pursued and laid for. Mine heart is full of sighs, mine eyes of tears. Where can I vent my full, oppressed bosom than into yours, whose faithful lips may for these few hours revive my drooping, wondering spirits, and here begin to wipe tears from mine eyes, and the eyes of my dearest children?”

Peace and Truth never could consummate their love, Williams believed, until a stake was driven between the practical affairs of civil society and confessional religion. All should be free to believe, or disbelieve, he said, according to the dictates of conscience. The work of civil society should be placed in the hands of the most gifted persons available without regard to religious confession. In such a world, Williams was convinced, men and women could pursue God without hindrance.

The courage to be clear

Clarity was a rare commodity in Williams’ day and is rarer still in ours. Politicians aspiring to maximize their vote count speak with polished imprecision. Frank speech is considered a rookie error. You aren’t supposed to say the quiet parts out loud.

“Politicians aspiring to maximize their vote count speak with polished imprecision.”

Congregations that span the ideological spectrum rarely hear sermons on culture war issues like immigration policy, reproductive health and gay marriage. Speak clearly on these matters, young pastors are told, and you will anger half your congregation. Much better to preach on the secrets of personal happiness.

Of course, not all preachers and politicians must appeal to a diverse audience. When your constituency is in broad agreement on the pressing issues of the day, preachers and politicians are allowed to speak clearly, so long, that is, as the audience dictates the message.

I used to enjoy listening to Jimmy Swaggart work his audience. When Jimmy introduced a tirade with “some of you aren’t going to like this,” you knew a standing ovation was waiting in the wings. Similarly, Donald Trump is free to trade in unfounded allegations and conspiracy theories because he understands the fears and prejudices of his chosen audience.

The clarity practiced by Roger Williams rarely found a favorable reception. The Church of England and the divines of Massachusetts Bay disagreed on many points, but all parties insisted that politics and religion be joined at the hip. Every religious pronouncement had political implications. Inevitably, politics bled into religion. To Williams, this was a recipe for cowardice and hypocrisy.

The courage to concede

Those who insist on ideological purity must dream of absolute victory. Roger Williams didn’t have that luxury. His desire to separate church and state was, at best, a fringe sentiment, and he knew it.

In The Bloudy Tenent, he confessed that “this discourse against the doctrine of persecution for cause of conscience” would gain much traction, “even among the sheep of Christ themselves.” Still, he persevered. “Having bought truth dear,” he cautioned, “we must not sell it cheap, not the least grain of it for the whole world; no, not for the saving of souls.”

“Having bought truth dear, we must not sell it cheap, not the least grain of it for the whole world; no, not for the saving of souls.”

Persecution was necessary, the religious establishment insisted, because eternal salvation was at stake. The lords of New England could tolerate disagreement on inconsequential matters; but when erroneous ideas had foolish people teetering on the lip of hell, they clamped down.

Only the power of love can draw us to the truth,” Williams answered. The only species of salvation worth troubling about must flow “from the love of truth, from the love of the Father of lights from whence it comes, from the love of the Son of God, who is the way and the truth.”

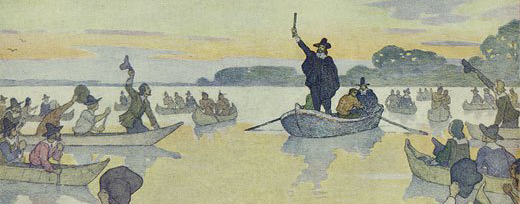

Williams could speak clearly because he wasn’t trying to win. He couldn’t erect a wall between church and state in England or in Plymouth or Massachusetts Bay. He couldn’t make the wider world safe for Catholics, Quakers, Baptists and atheists. But he could carve out a little patch of freedom in the New World, and that became his life’s work.

Our fear of failure causes us to speak in garbled platitudes. Preachers and politicians (in these latter days it is difficult to tell them apart) are afraid to challenge established opinion because, as Dylan put it, they “just want to be on the side that’s winning.”

“We speak as much truth as the market will bear.”

We say what we are expected to say. We speak as much truth as the market will bear. We lie about our history. We lie about sex and gender. We lie about guns and empire. We fling a curtain of denial over genocide, rape and plunder. We shave off shards of pleasantness, then lapse into silence.

The courage to cooperate

Like Williams, we inhabit an age of political and religious upheaval. We don’t want to compromise our principles in the slightest particular. Liberal purists call their ideological opposites “toxic”; purists on the right regard their enemies as literal demons. Christian denominations are fracturing along ideological lines. In the political arena, liberals and conservatives wage uncivil war. Our opponents aren’t just wrong; they are devils.

Williams never shrank from controversy. Like all Puritans, he was a despiser of “Papists.” He expressed his disapproval of Quakers in a screed marked by extravagant vitriol: George Fox Digged out of his Burrowes. Yet all were welcomed to the haven he had planted in Providence. He insisted on the freedom to follow the truth wherever it led and extended that freedom to everyone else. In the unlikely event that an atheist, a Hindu or a Muslim wandered into his community, Williams said they should be welcomed as equals. The strident clarity of Williams’s religious opinions didn’t stop him from cooperating with everyone and anyone. He understood that genuine cooperation requires mutual clarity.

The courage to question

Roger Williams worshipped a mysterious God. Eschewing all denominational ties, he called himself a Seeker. Yet more truth would be revealed in God’s good time. No mere mortal possessed a corner on truth. “Precious pearls and jewels, and far more precious truth, are found in muddy shells and places,” Williams wrote in The Bloudy Tenent. “The rich mines of golden truth lie hid under barren hills, and in obscure holes and corners.”

Roger Williams worshipped a mysterious God. Eschewing all denominational ties, he called himself a Seeker. Yet more truth would be revealed in God’s good time. No mere mortal possessed a corner on truth. “Precious pearls and jewels, and far more precious truth, are found in muddy shells and places,” Williams wrote in The Bloudy Tenent. “The rich mines of golden truth lie hid under barren hills, and in obscure holes and corners.”

Of one thing Williams was certain: Those with the power to dictate truth rarely possessed it. So had it ever been. “The unknowing zeal of Constantine and other emperors did more hurt to Christ Jesus’ crown and kingdom,” he declared, “than the raging fury of the most bloody Neros.”

Truth had been defended by a bloody sword for so long it was all but impossible to find. “By this means Christianity was eclipsed, and the professors of it fell asleep,” he lamented. “Babel, or confusion, was ushered in, and by degrees the gardens of the churches of saints were turned into the wilderness.”

Here too, Williams was right. Before we can speak clearly, we must acknowledge our confusion. The world is too much for us. We are adrift on a sea of bewilderment. But Williams was convinced that, just as God has spoken in Jesus Christ, God would speak again. It was that confidence that fired the spirit of prophecy, in his day and in ours.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

Roger Williams, John Cotton and the future of the American experiment | Analysis by Alan Bean

Roger Williams, the father of American deconstruction | Opinion by Alan Bean