On a recent trip to Colonial Williamsburg and Richmond, Va., I saw things from a different point of view.

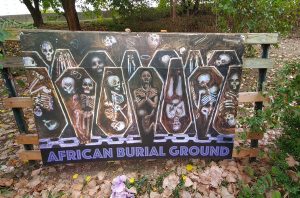

As I looked into racial minority issues, predominantly those of Africans, I was shocked at how melanin became evil. It is one thing to read about slavery in a textbook; it is entirely another to walk where inhumanity trod.

Retracing the steps of those brought here beginning in 1619, who were sold into indentured servitude, made me wonder what in my life I could tap into even to begin to empathize with these people. The closest I could come up with is my rights as a member of the LGBTQ community.

Haydn Primrose

To see rights that others take for granted be placed for a vote. To ask other people if I was, indeed, a whole human deserving of the same rights they already had. To wait to see if other people will recognize my worth as a creation in the Imago Dei.

Do not miss what I am saying. I am not in any way comparing the struggles of the LGBTQ community in the 21st century with those of Africans in the 17th century. I am merely trying to find something in my own life that even remotely brings me into a closer understanding of the atrocities that were forced on them.

When I think of how European white colonizers placed the African black “things” in chains in Richmond and marched them from Lumpkin’s Jail to the auction yard some 150 yards away, it makes me reflect on the times on my family’s farm when we would go to the livestock auction. We would look at the bovines to gauge whether we would want to spend our money on them and if they could offer us a return on investment. Oh, the similarities.

“When we moved from the site of Lumpkin’s Jail and walked to the auction site, I made myself walk as if I was bound in chains.”

When we moved from the site of Lumpkin’s Jail and walked to the auction site, I made myself walk as if I was bound in chains. I sent myself back to a time when I was seriously injured and did not know if I was going to survive. I relived the terror and fear that the prospect of losing my life presented to me, and then I added in the restrained and chained walk.

I could do that for only about 20 feet before anxiety kicked in to the point I, in the vast open space, amongst friends and colleagues in a safe space, felt claustrophobic and overwhelming dread. I had to break out and move my mind to something else.

I could do that for only about 20 feet before anxiety kicked in to the point I, in the vast open space, amongst friends and colleagues in a safe space, felt claustrophobic and overwhelming dread. I had to break out and move my mind to something else.

What would it have been like for those in a foreign land? They would have had no one they knew (or at least separated from anyone familiar). They would be amongst those who would have no problem harming them since the colonists did not see the Africans as humans but as property. In mere moments, they would be potentially deemed worthless and hanged by the neck until the noose took the very breath of life that others denied they had. I could break from this mental exercise, they could not. They were completely helpless, like livestock.

But what does this have to do with the whitewashing of history? Some people would have us believe some slaves were happy to be slaves. They loved their masters and never would have wanted to be set free. Some people would have us believe the slaves were treated well and given proper care. While this may be true for a small minority of slaves, one would have to do mental gymnastics to think this was the norm. Yet, some have done their best to ensure that the cruelty of the South’s “peculiar institution” is tamed down a bit so as not to make people uncomfortable. As if our comfort with slavery’s past is what is essential.

I asked my 5-year-old godson to pick colors to see how far “whiteness” goes in superiority. I asked, “What color do you think is happy?” He picked up a yellow crayon. I asked, “What do you think is good?” He picked up a white crayon. I asked, “What do you think is bad?” He picked up a black crayon. I asked, “What do you think is evil?” He again held up the black crayon.

No wonder we whitewashed Jesus. If Jesus is pure, holy, righteous and superior, then, of course, he would be white. What other color could Jesus be?

“A white Jesus was necessary to make the biblical passages about slavery work.”

White Jesus was the way to show that whiteness is good, black is bad. As a black entity, you are not a person. You are not good. You are not right. As a white human, you are superior, intelligent, civilized. A white Jesus was necessary to make the biblical passages about slavery work. You could not have a brown Jesus telling white people that Black people are bad. No, that just will not fit the narrative.

When we look at how our culture shapes our words or how our words shape our culture, it is not hard to see why our culture has associated the word “black” with bad or “bad” with black. It makes it easier for American history to disassociate how the Black slaves were treated and diminish its inhumanity. If we can take an immutable characteristic and tell a person that is what makes them lesser than the white person, then it is not hard for the white person to convince themselves they are superior.

For Americans to deal with its slavery past, we must wrestle with the discomfort, acknowledge the real history of Africans in 17th century America and how America’s history with race still has not been completely dealt with 400 years later.

Only a genuine desire to go back and understand history as it was, not how we want it to be, will afford Americans the ability to change how we go forward. May we have the courage and compassion to sit with our religious heritage and deal with the knowledge that it was manipulated to give permission for this to happen in the name of God.

Haydn Primrose lives in Colorado, is a board-certified chaplain and student at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky.

Related articles:

Whether blind, blurry or oblivious, failure to see whiteness distorts God’s image in others