“The Good Shepherd” is a mosaic dating back to 425 AD that sits over the entrance to the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy.

I have often wondered what Christianity would look like if the parables of Jesus found concrete expressions in Christian doctrines. For example, “We believe that being a neighbor is an essential element to the praxis of the Christian faith.”

I am not sanguine that such a thing will happen. Here’s why.

The parables of Jesus attack the closely guarded inner nature of people. Furthermore, they are action based. And finally, with most of the parables, it is quite easy to defend the antagonists. So, I believe that, by and large, in modern American Christianity, parables will achieve the status of the Grimm brothers, or Hans Christian Anderson — fairy tales meant to help people feel good.

“In modern American Christianity, parables will achieve the status of the Grimm brothers, or Hans Christian Anderson — fairy tales meant to help people feel good.”

In this vein, I would like to look at a famous parable, commonly called The Parable of the Good Shepherd. I would also like to suggest that the existence of the “good shepherd” is a mythology in the present-day church.

Found more in paintings than pulpits

Here is a parable of Jesus found more in paintings and pictures than in the pulpit. Located in the New Testament Gospels of Mathew and Luke, this brief parable talks about a shepherd who owns a hundred sheep but discovers one of his sheep is missing. Leaving behind 99, he goes looking for the missing one, finds it and returns home rejoicing.

Make no mistake about it. It is a beautiful picture. The shepherd is so invested in the sheep that he goes looking for it — keeping aside possible personal danger. It is the story of a strong relationship. In a world where it is usually the sheep that need the shepherd, this is a story of a shepherd whose life seems empty until the missing sheep is finally home.

Phillip Thomas

It is a beautiful story meant to evoke a picture of Jesus, as the Good Shepherd, who leaves all to look for a missing sheep. Sadly, it is not a picture one finds in the reality of the modern-day American church.

In my 30 years of living in a “Christian” context in America (and frankly in the years of living in a similar context in India), I do not believe I have ever heard an entire sermon on this parable. (If you are a preacher who has preached a whole sermon on this parable, please accept my apologies.)

“I do not believe I have ever heard an entire sermon on this parable.”

It is worth asking the question, why don’t preachers preach a whole sermon on this parable? After all, this has been captured in pictures and Sunday school stories for a very long time. What makes it even more puzzling is that another parable, The Parable of the Prodigal Son, found in the same chapter in the Gospel according to Luke, has been preached countless times.

The main reason pastors don’t preach about the Parable of the Lost Sheep is that it is a parable not often followed in modern American Christianity. Let me offer a few reasons why.

To understand this, examine the nature of the relationship of most pastors (a word taken from late Middle English: from Anglo-Norman French pastour, which, in turn, is from the Latin word pastor which means “shepherd”) with their congregations.

Reason 1: Transactional relationships

The churches, despite their best explanations, have a largely transactional relationship with their pastors. Most pastors don’t have deep relationships and usually come into the picture mainly to solve a problem or conduct rituals (christening, baptism, marriage, funerals).

Churches usually are described based on their theology (conservative, liberal, charismatic) and size (large, medium, small). There are many other descriptors. But I have never heard a church describe itself as deeply relational — one where being a part of the church requires a deep commitment to each other, exemplified and personified by the leadership.

It must be noted that many large churches have started “small group” ministries to create “care” among the members. But this looks much more like a leadership decision to manage the care of members rather than an essential fabric of the church’s DNA. But that’s only my opinion.

Reason 2: Pastor as CEO

Pastors are CEOs. The current church calls more for a CEO, or even perhaps a teacher (or a modern-day rabbi), than a shepherd. A friend, J.R. Briggs, often refers to the three Bs that engage the focus of modern pastors — building, budget, bodies. But while churches, and pastors, have embraced the CEO role, here are some differences, from my point of view:

“A CEO deals with the portfolio; a shepherd deals with the individual sheep.”

A CEO deals with the portfolio; a shepherd deals with the individual sheep.

A CEO deals with overall growth and health; a shepherd cares very deeply about the individual sheep.

A CEO is concerned about overall direction; a shepherd invests in maintaining personal relationships with individual sheep.

Most CEOs only have relational capital invested in those people whose contributions matter to the bottom line. That is the nature of CEOs, and the larger the organization, this perspective is more pronounced and evident.

One might say it is impossible to be a shepherd when the churches and their organization have become so big and complex. My response: Nothing says the church organization needs to be this big. The only truly large organizations are found in the Old Testament. The New Testament has networks of smaller organizations, and even most of the epistles would not have made it to the accepted canon if these networks weren’t willing to share among themselves.

Reason 3: Meanings of ‘sin’ and ‘lost’

We take words and create a theological nomenclature with them. Sadly, in the Christian church, lostness is equated with “sin.” Yet a critical examination of the two parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin should reveal a different answer. How does a coin lose itself? How does the sheep wander away unless the shepherd wasn’t doing his job (most shepherds in Jesus’ time were men)? How is any of this intentional sin?

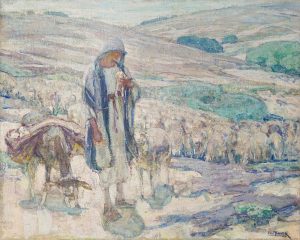

“The Good Shephered,” Henry Ossawa Tanner, Crystal Bridges Museum.

However, it is this interpretation, combined with a Western individualistic perspective, that allows churches to assign a negative moral value to the word “lost” — meaning lostness happens only because of the person, and neither the shepherd/owner nor the community they are a part of bears any responsibility. This further allows the shepherd (modern-day pastor) to shirk responsibility to go after the “lost,” lest it point a flashlight at their misplaced priorities.

This parable challenges the portfolio view of relationships and homes in on the failure, and beauty, of an interpersonal relationship that needs to exist in the Christian community that includes the shepherd and sheep.

Reason 4: Warped view of grace

We have a warped understanding of grace. Grace needs “lostness” to manifest itself. The two are linked in our human world. In commercial terms, being “lost” is the market for a product called grace. We must embrace lostness so that grace may be free flowing and abound.

Reason 5: Focus on hardware, not software

We focus on hardware and not software. This builds on what I wrote in Reason 2. We can get our heads around the strategies, programs, structures and ministries. Pastors can direct people on what to do but don’t necessarily know how to direct them on who to be.

“Pastors can direct people on what to do but don’t necessarily know how to direct them on who to be.”

The who to be is defined morally, and the focus is on doing. “Being” is absent because most sheep do not have a relationship with the shepherd on emulating being. The Apostle Paul, in his letter to the Corinthians, asks them to “imitate him.” I can honestly tell you that in my 50-plus years in the church I have never had a relationship with a leader (except one) whom I knew enough to want to imitate. Peter Drucker famously reminded us that “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Churches need to know they are not immune from this happening.

In modern evangelical America, the shepherd makes life unlivable for the sheep because it is the shepherd who is given the power to classify what a “good” sheep is. “Good sheep” in my definition is the sheep that stayed and fits into the culture, theology and perspective the shepherd lays out. Any sheep that doesn’t fit their exacting and uniform description is made uncomfortable, and so if the sheep leave. why blame the shepherd?

Sadly, the Parable of the Good Shepherd turns this mythology on its head.

Who will we be?

Why is this important? I am not writing to proclaim the death knell of the church. I write because the church, or any organization that claims to serve people, must decide whether their focus is on organizations and power or deep individual relationship. The truth is that focusing on the organization provides the highest personal economic and power return on investment to a pastor, and individual relationships provide the least.

“Adherence to rituals only proves that people are like sheep; this does not point, necessarily, to the presence of a shepherd.”

I believe Jesus came for the latter, but watching the church in America tells me I am in the minority, thus proving that these parables are nothing but feel-good fairy tales with very little practical impact on the adults who contribute to the 3Bs — bodies, budget and building.

It is an indisputable fact that churches have lost members in the recent past. Many try to provide explanations, but there is a reason I am willing to bet on. Most people who left never truly experienced the shepherd in Jesus’ parable. This might well be the church’s Achilles heel.

We should ask why many people stay despite some leaving. The truth is that rituals are the customer engagement tool for churches, and this has been proved as a trusted tool for the church. But adherence to rituals only proves that people are like sheep; this does not point, necessarily, to the presence of a shepherd.

Should a church desire to turn things around, may I suggest that living out the Parable of the Good Shepherd is a great place to start.

Phillip Thomas, originally from India, now makes America his home, along with his wife of 29 years and his three children, in the Philadelphia area. He works for a global bank and continues to wrestle with his faith and Christianity.

Related articles:

Like it or not, we are like sheep – including our vulnerability to ‘thieves and wolves’ | Opinion by Wendell Griffen

How to live in perilous times: a pope and a priest’s contrasting responses to Hitler’s Final Solution | Opinion by Mark Wingfield