The staunch theological and political support for the state of Israel that the Southern Baptist Convention is known for today was preceded by decades of diverse opinions among Baptists about the Zionist movement that eventually birthed the Jewish nation in 1948.

So says Walker Robins, historian of American religion, lecturer at Merrimack College in Massachusetts, and author of Between Dixie and Zion: Southern Baptists and Palestine Before Israel. He spoke at a Nov. 3 webinar hosted by the Baptist History and Heritage Society.

Walker Robins

In fact, a convention that would go on to adopt numerous pro-Israel resolutions rejected repeated measures at its 1948 annual gathering to simply thank fellow Southern Baptist and then-President Harry Truman for his role in the establishment of Israel, Robins said.

“Most Southern Baptists really didn’t prioritize the Palestine question as a political question,” he said of what was then a decades-old international debate about how to divide the region between Jews and Arabs. “There wasn’t a widespread sense that Southern Baptists did, or should have, a particular perspective on the Palestine question, or on Zionism or on the aims of the Arab population.”

Before 1948, Robins added, “what I found instead is that Southern Baptists had a number of different priorities that shaped the ways in which they thought and wrote about Palestine, about the land, about the people and about the politics of the region.”

Robins’ book examines those perspectives as shared by Baptist tourists, premillennialists, converts from Judaism and Arab pastors, among others. But during the historical society’s fifth “Making Baptist History Public History” webinar, he focused on the writings of four SBC missionaries and a publication editor who expressed a range of attitudes about the Palestinian question, about Zionists and Arabs.

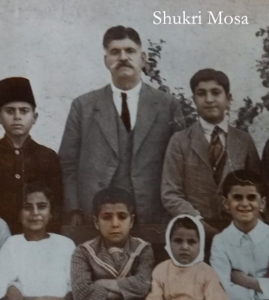

Shukri Mosa and family

Robins began with Shukri Mosa, a Palestinian Muslim who converted to Christianity and was commissioned as a pastor in the U.S. before returning to his homeland as a missionary in 1911. His articles in SBC magazines and in the Baptist Standard in Texas conveyed his concern that the Zionist movement could encroach on his evangelism efforts in and around Nazareth.

“He was warning Baptist leaders back home that the Zionists were purchasing land around Nazareth. He warns Baptist leaders with the Foreign Mission Board that Zionists were interested in possibly establishing a school near Nazareth,” the historian explained.

Robins cited a 1922 Baptist Standard article in which the missionary complains that “‘these new Jews, or at least the majority of them, are irreligious people. They do not believe in the Bible as the ancient Jews and we do; they do not recognize the Sabbath; they eat any kind of meat; they are very rarely seen in synagogue; they are immoral. … They have a great hatred to Christianity and Christians.’”

But Mosa’s critique of Zionists was not a case for political or Baptist support for the Arab cause in Palestine. “If you actually look into the context of these articles and the things that he was saying about Zionism, what he’s really trying to do is light a fire among Southern Baptists and to help get them to extend material support for the mission,” Robins said.

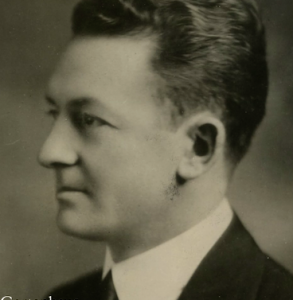

Leo Eddleman

Southern Baptist missionary Leo Eddleman was at first optimistic about Zionism when he arrived in Palestine from the U.S., Robins said.

“He is actually initially very enthusiastic about it potentially offering an opening for Southern Baptist missionaries who were seeking to reach Jews for Christ. And this hope was something that was shared by most of the Southern Baptist missionaries that began to arrive starting in the 1920s.”

Eddleman, who served in the region from 1936 to 1939, was encouraged by a component of Zionist ideology that connected Jewish identity with nationhood, not religion, Robins said. “So, missionaries really seized onto that and argued that if Jewishness is a matter of national identity rather than religion, then it should not be a problem for Jews to convert to Christianity.”

But the missionary eventually was disappointed to learn that the Zionists themselves did not see it that way, Robins explained. “In fact, most Zionists he spoke to about the issue pushed back against his message in the name of Zionism, and this really started to frustrate him, and you can hear his frustrations within months of him arriving on the ground in Palestine.”

Frustration grew into distrust, and by the mid- and late-1940s, Eddleman would write to President Truman to warn of possible Zionist connections to Communism.

But where Eddleman saw limitation, Robert Lindsey saw opportunity, Robins said about the Southern Baptist missionary who arrived in Palestine in the mid-1940s.

But where Eddleman saw limitation, Robert Lindsey saw opportunity, Robins said about the Southern Baptist missionary who arrived in Palestine in the mid-1940s.

“Lindsay himself came to very, very deeply identify with the Zionist movement. He was actively inspired by it,” Robins said. “He was this great Hebrew scholar, and he starts to develop a vocabulary that missionaries could use to change the way in which Christians talked about aspects of Christianity in the Hebrew language. He wants to make it friendlier to Jewish … ears. He calls for really renewing the Christian faith in light of its Jewish roots.”

The Jewish nationalist movement is “something that the mission needs to adapt itself to, and so that’s going to guide the way that he talks about Zionism when he’s writing back to Southern Baptists back home,” Robins said.

Jacob Gartenhaus

Another SBC missionary to embrace Zionism was Jacob Gartenhaus, a convert from Judaism whose ministry was helping churches in the American South evangelize their Jewish neighbors.

His theology-laden writings about the virtues of Zionism were influential across the convention, Robins said. “He believed that the covenantal promises between God and the people of Israel were still active, that Jews remained God’s chosen people, that Palestine remained their promised land and he believed that these covenantal promises would be fulfilled in concert with the second coming of Christ.”

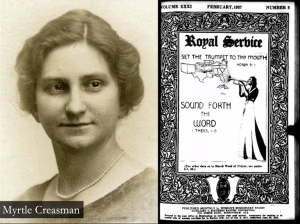

One thought leader heavily influenced by Gartenhaus was Myrtle Creasman, program editor for Royal Service, a periodical of Woman’s Missionary Union that educated Southern Baptists about the convention’s various mission fields, Robins said.

Myrtle Creasman and a copy of “Royal Service,” which she edited.

“Myrtle Creasman is sneakily one of the more important Southern Baptists of the early 20th century. … She followed Gartenhaus. She was a premillennialist. She believed Zionism was part of God’s plan for history. So, when she is writing about Palestine as a mission field, she brings in that perspective and those ideas would begin to be distributed throughout the convention.”

These figures “are reflective of this broader diversity that you see within the SBC during these years,” Robins said. “You don’t have a widespread sense of a single Southern Baptist perspective on the Palestine question.”

But a nearly universal theme among Southern Baptists at the time, regardless of how they viewed the Palestine question, was “to identify the Zionist movement with Western civilization and modernity and material progress, in contrast with the Arabs whom they viewed as backward or quaint, at best,” he added.

Allison Tanner

It’s clear that Southern Baptists were viewing the Palestinian question as a religious, not partisan, issue, Allison Tanner noted in her response to Robins’ presentation.

“One of the frames the missionaries frequently had was that of pilgrimage, that of encountering Palestine as a holy land. So, when they think of Palestine, they don’t think of it in political terms, they think of it in spiritual terms,” said Tanner, pastor of public witness at Lakeshore Avenue Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif.

Missionaries and other travelers at that time also clearly viewed Zionists and Palestine through the lens of biblical prophecy, she said. “That can be seen in very different ways — premillennial, postmillennial — but one of the frames is that there is a divine plan, or there ought to be a divine plan, for what happens in this land.”

Related articles:

Carver School of Social Work was a victim of American fundamentalism, authors explain

Scholar traces how Black churches became centers of political engagement

Meet the Baptist pastor who helped cultivate the Lost Cause narrative

Baptist History and Heritage Society receives grant, will launch new webinar series