For some time now, Christianity has been on the decline. According to a September 2022 Pew study, people identifying as Christian have decreased from 90% of the U.S. population in 1972 to 64% in 2020.

But it’s not just researchers who are talking about this.

As of Dec. 6, 2020, the hashtag “#exchristian” had 696.7 million cumulative views on TikTok and was assigned to more than 68,600 posts on Instagram. When looking specifically at evangelicalism, the numbers nearly double. The hashtag “#exvangelical” was viewed 1.1 billion times on TikTok and was assigned to 105,000 posts on Instagram.

Brandon Flanery

People of all backgrounds are processing this great exodus, finding whatever resources they can, especially via social media, to explain this change. But how are pastors and churches reacting?

In a 2021 sermon, controversial pastor Matt Chandler called leaving the faith “some sexy thing to do.” He denounced the process of critiquing one’s childhood faith, saying, “If you ever experienced the grace and mercy of Jesus Christ, actually, that’s really impossible to deconstruct from. But if Christianity is just a moral compass, I totally get it.”

But is this true? Are millions abandoning their faith because Christianity is “just a moral compass?” Because it’s “sexy” to do so?

An online survey

To uncover why people are leaving Christianity, I went to those who would know: the people leaving. What follows is not a typical randomized national sample; it is based on responses to a social media query with a large and diverse response.

Reaching out through varying social media platforms, I received 1,200 responses to a survey that asked six questions:

- What existential framework were you raised in?

- What existential framework do you find yourself in now?

- What initiated the change (the very first instance where things began to shift)?

- What was the final reason you made the change (the straw that broke the camel’s back)?

- What does your current existential framework offer you that your previous one did not?

- What does your current existential framework not offer you that your previous one did (for example: what do you miss)?

Where they’ve come from and where they’re going

After receiving the open-ended responses, I went through and notated themes, coding them to create quantitative results.

Here’s what I found about the faith traditions my respondents came from and how they identify today.

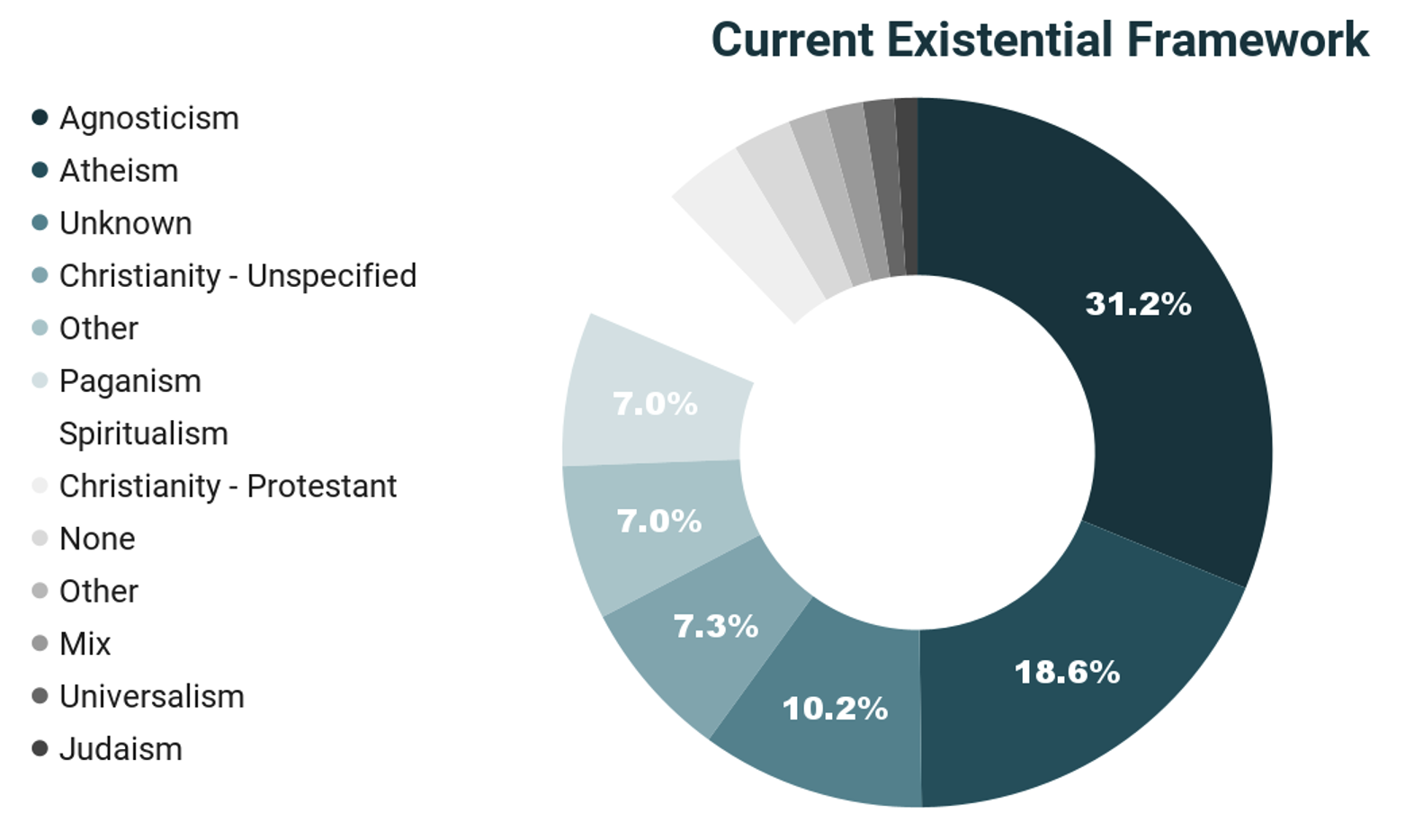

After stripping out all respondents who did not have a faith origin of some flavor of Christianity, I had 1,050 responses left. Of those, here’s the breakdown:

After the respondents deconverted, existential frameworks became far more diverse:

It’s important to note that while many are leaving the faith altogether, there are still people remaining in Christianity, choosing a different denomination or using language like “Jesus follower” rather than explicitly identifying as a “Christian.” This type of individual makes up a little more than 10% of those surveyed.

LGBTQ discrimination a big reason

But what about the bigger question: Why?

Andy Stanley, pastor of North Point Ministries, one of the largest churches in the United States, wrote and spoke about this question. He believes some reasons include that the Bible contains contradictions, that there’s suffering in the world, bad church experiences, bad Christian experiences, and Christians can make church about a building rather than a faith experience. While he did get a few reasons correct, I think Stanley would be surprised by what’s ultimately motivating people to deconvert from traditional Christianity.

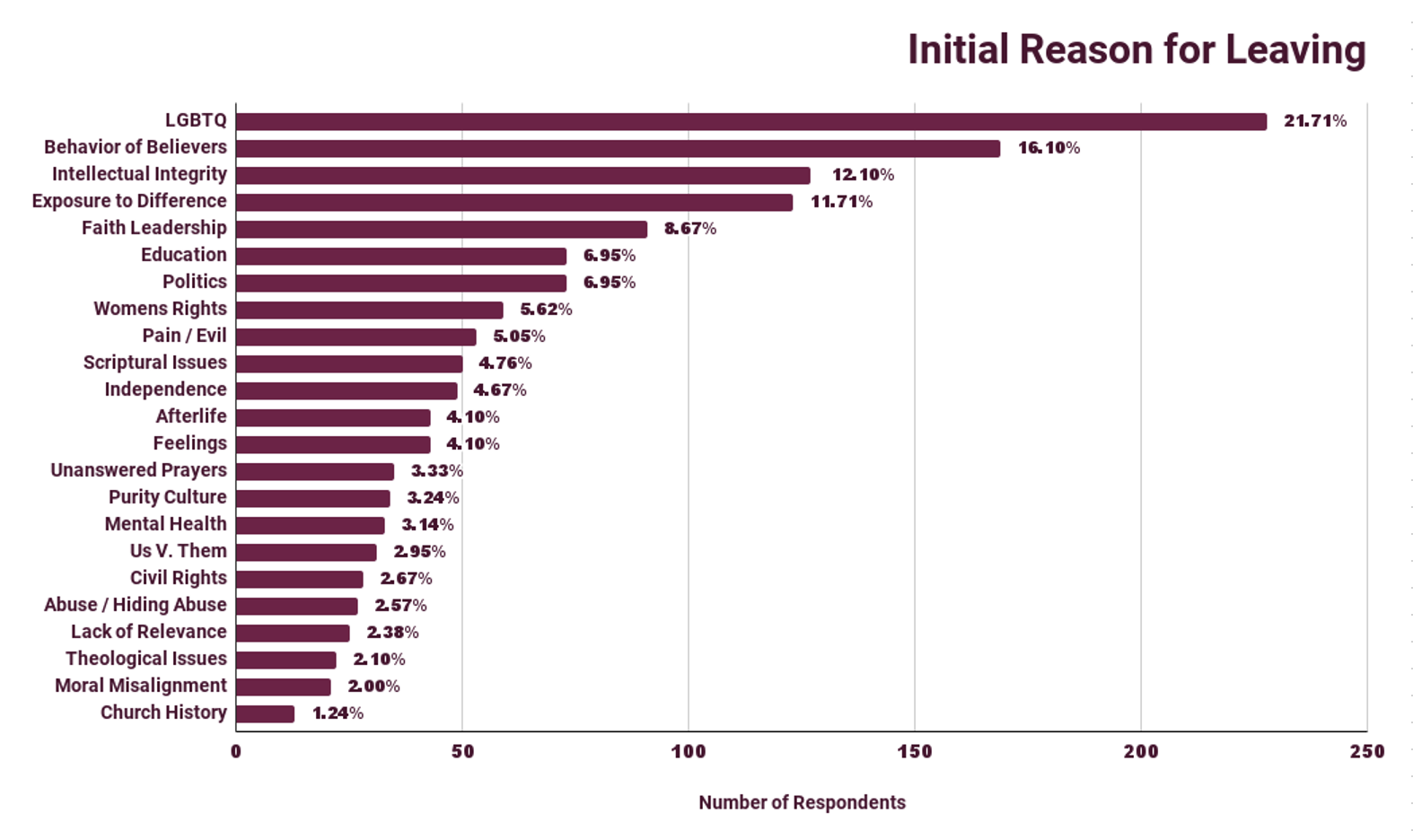

When it comes to the moment people first began doubting their faith, LGBTQ acceptance is the most common reason, followed by the behavior of Christians, and then things not making sense on an intellectual level (an example of this would be: I couldn’t reconcile how there can be an all-powerful God and evil).

Yes, a good number of my respondents were queer, and not being accepted by their congregations was a critical motive for leaving. However, the majority of respondents were straight and cisgender, and they ultimately started doubting Christianity when they were told they couldn’t support their queer friends and family. Unable to rectify their love of LGBTQ people with the church, they chose LGBTQ acceptance. Some responses:

- “I couldn’t continue to ignore the treatment of LGBTQ and other marginalized people.”

- I started doubting because of “the way the church treated people of the LGBTQ community and anyone who didn’t dress/think/act/look like them.”

- “I couldn’t understand why God would create LGBTQ people in a form my church claimed he hated.”

- “The first thing that challenged my viewpoint directly was meeting LGBTQ people and seeing that they were kind, thoughtful and deserving of respect.”

- “The first thing was noticing how what Christians preached/practiced didn’t seem to align with that I knew to be the character of God, including views on the LGBTQ community, immigration, adoption, mental health issues, ‘mission work,’ and just general treatment of others.”

The behavior of Christians

Beyond the issue of LGBTQ inclusion, Stanley did get one thing right: Many people object to the behavior of Christians, and that’s not something new.

When writing a letter to C.S. Lewis about potentially converting to Christianity, author Sheldon Vanauken wrestled with this exact thing in his book A Severe Mercy:

The best argument for Christianity is Christians: their joy, their certainty, their completeness. But the strongest argument against Christianity is also Christians — when they are somber and joyless, when they are self-righteous and smug in complacent consecration, when they are narrow and repressive, then Christianity dies a thousand deaths.

Apparently, some things never change — the behavior of Christians is a massive stumbling block for people coming to the religion and walking away. However, instead of dying a thousand deaths, Christianity is dying millions.

Trump: The last straw

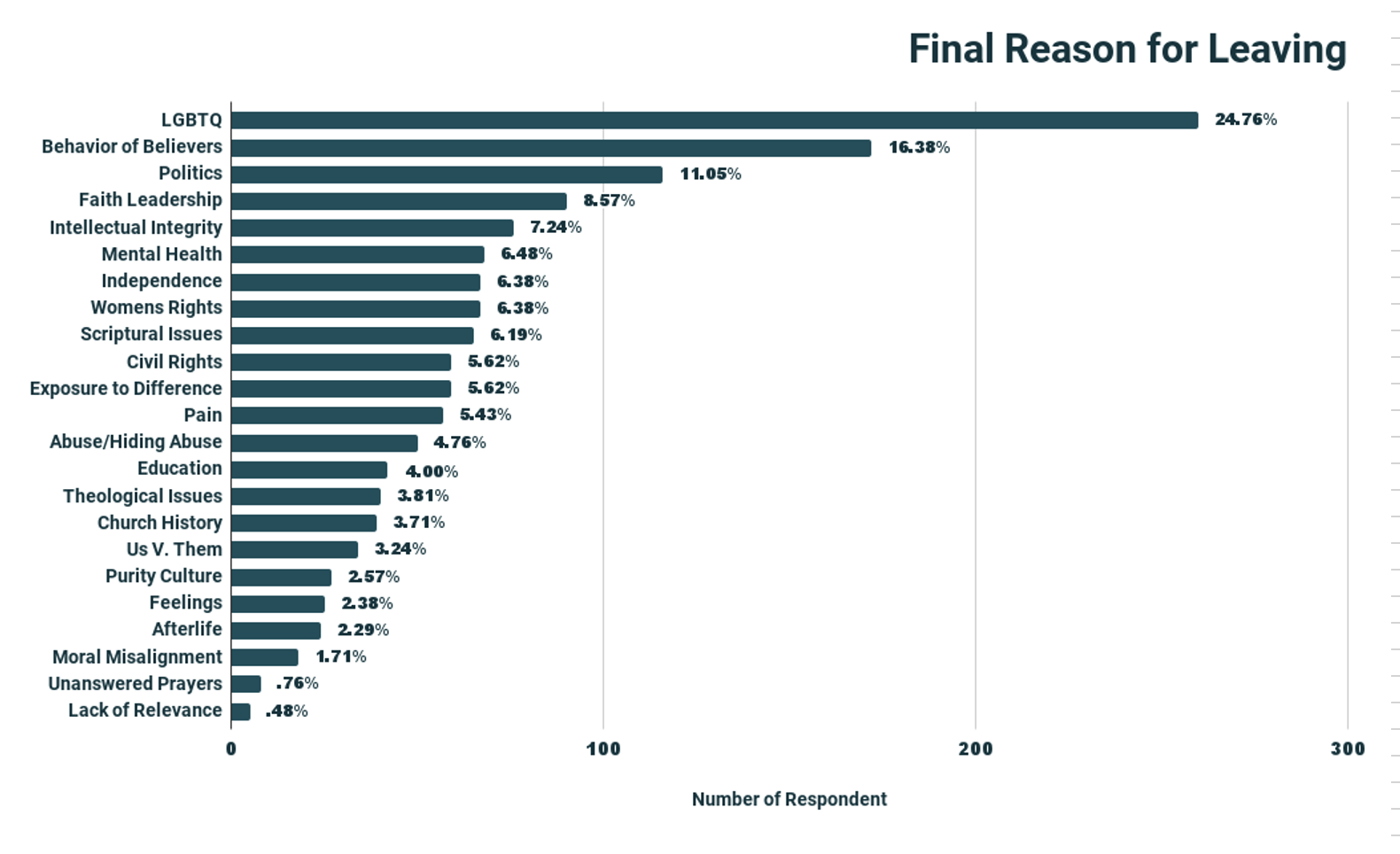

To better understand why people are leaving, it’s important to look at the final reason, what the survey referred to as “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” While much of the data remains the same, it’s important to note that one reason moved from seventh place to third: politics.

For many respondents, politics is what finally motivated them to leave Christianity. Specifically, many referenced the election of Donald Trump and the support he received from the evangelical community. In fact, the name “Trump” was mentioned 81 times in the survey responses as a key reason someone left Christianity. For example, these were some respondents’ experiences:

- “A culmination of events over the course of a few months starting in the summer of 2020. I had a fight with my father-in-law over the Confederate flag being a symbol of racism, he stopped speaking to me for months and it became a whole thing. The rise in glorifying Trump and fascism disguised as democracy.”

- “Seeing so many friends and family that claim to love and follow Jesus pledge their allegiance to nationalism and Trump.”

- “The 2016 election. I wanted nothing to do with a group that supported Trump and his insane ideology under the pretense of faith.”

- “Trump was the last straw for me. Seeing a person who should be the opposite of what Christians are called to be, being supported by evangelicals everywhere, really woke me up to some harsh American/conservative realities and how we’ve bastardized Christianity like others before to push not love or Christ but instead Republican dogma steeped in racism, sexism and greed with the Bible as a manipulation tool to get people to conform to these particular ideals that have nothing to do with the Gospels.”

‘They’ll know we are Christians by our love?’

Ultimately, Chandler and those who follow his teachings are wrong: Christianity isn’t losing followers because leaving is “some sexy thing to do.” It comes down to how people are being treated, specifically marginalized communities.

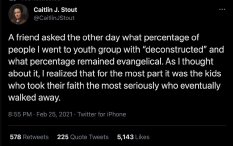

These responses make me think of a Tweet by Caitlin J Stout, a lesbian Christian:

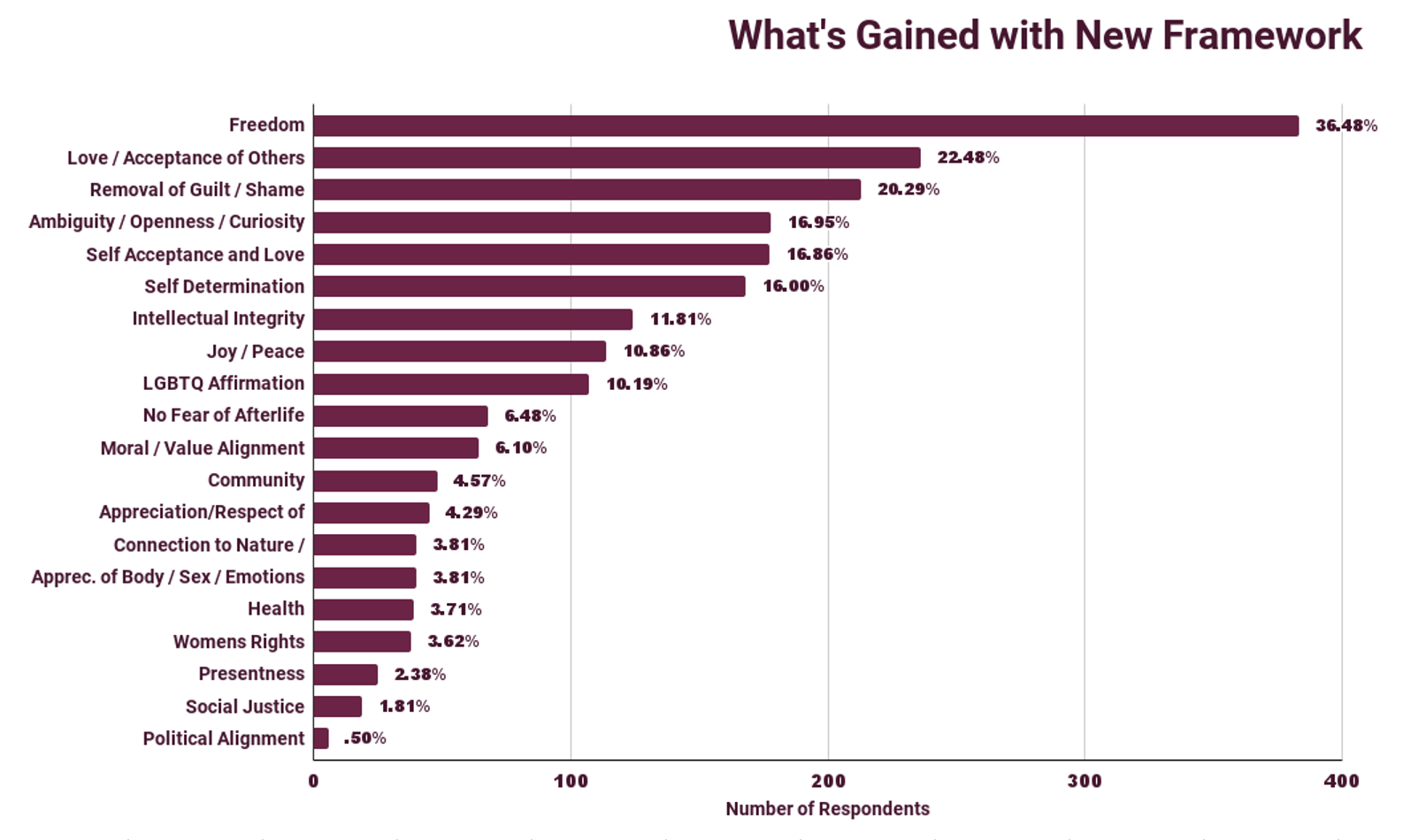

Christianity is a religion that boasts about its love, but people are not seeing it, and they’re walking out the door. With this in mind, it’s no wonder that loving and accepting people is the second most valuable quality people gain when they leave Christianity.

I recently spoke with someone about my research, someone who is very much still in evangelicalism. When I showed him the results, his response was, “It’s not surprising since God’s word warns us all about what will take place in the last days, but his remnant will hear and know the truth.” He then quoted Jude 1:17-19: “But you, beloved, remember what was foretold by the apostles of our Lord Jesus Christ when they said to you, ‘In the last times there will be scoffers who will follow after their own ungodly desires.’”

Freedom

These data tell me people aren’t leaving Christianity to live immoral lives. Yes, a few people mentioned they get to have premarital sex and do whatever they want, but that’s not the main reason.

I marked “freedom” as a category any time a respondent specifically used the word “freedom.” But freedom is always attached to action. Freedom to live their own lives. Freedom to have sex with whomever they want.

While these answers were present in the survey, they would have been assigned to three categories: “freedom,” “self-determination,” and “appreciation of body/sex/emotions.” However, the vast majority of people connected freedom to love. Their words:

- “The freedom to love and accept anyone, no strings (aka ministering) attached.”

- “Openness to accept other people from other religions with open arms and an open mind. Freedom to love any and all people despite their background or sexual preferences.”

- “The ability to love people in a much more whole way. I don’t have to pray for them and want them to change and I don’t have to judge them for the way they live.”

- “One of the teachings of our Bible is “who the Son (Jesus) sets free is free indeed.” Works really nice as a church song or devotional content. But I realized when I opened up to the possibility that all are welcome, literally all with no exclusions — the queer community, women in positions of spiritualism leadership, other religious traditions experience God too, there are no limits on God’s presence and how that spirit moves among us … — then I knew it. That was freedom and love and grace and kindness and all the goodness of the God I had been told about. It was all still there just truly, finally free.”

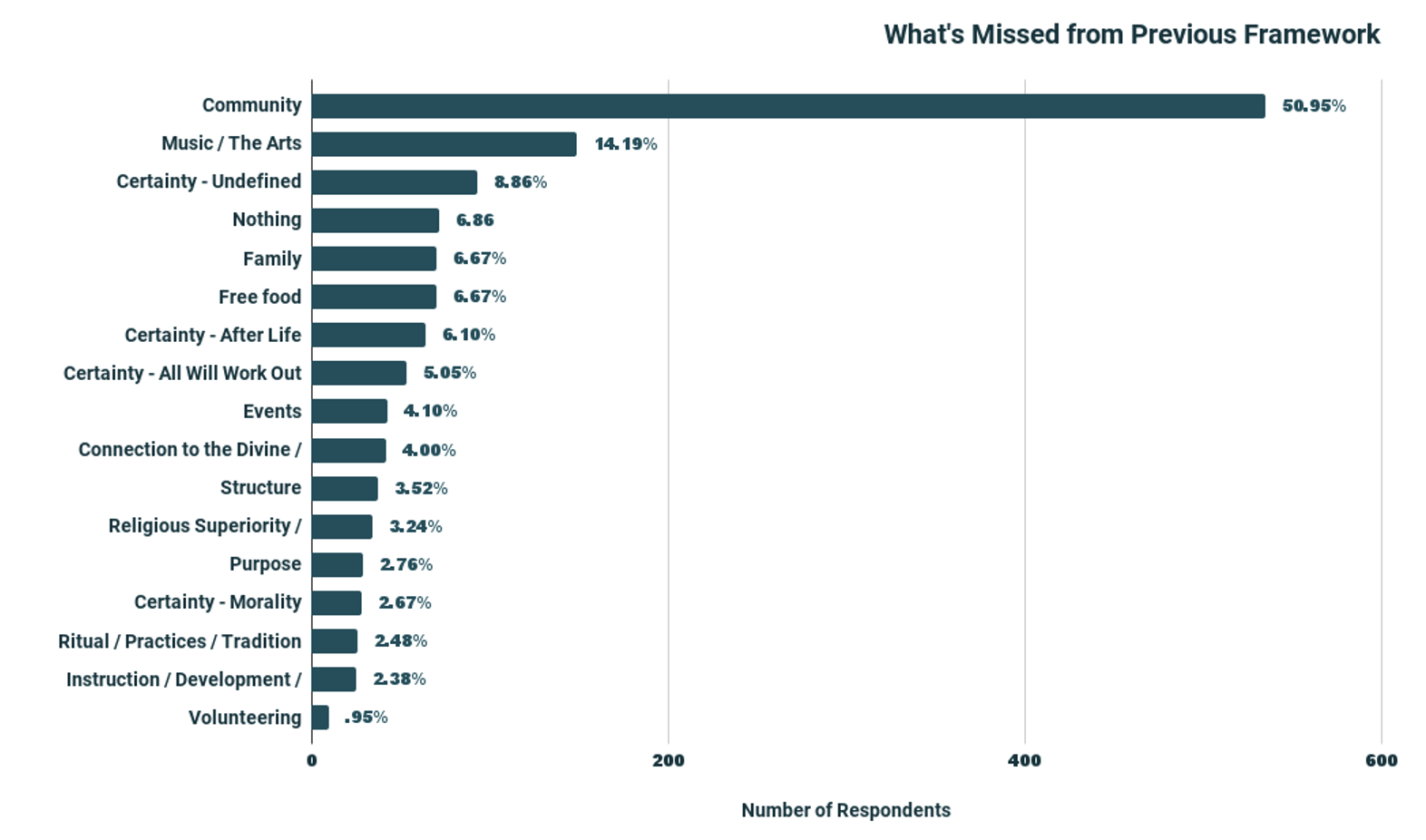

The price we pay: Community

In most of these responses, there is a yearning to do better, to be better, to love better. But it seems like it’s coming at a price, and a steep one.

The final question asked what people missed about Christianity. For many, it won’t be a surprise that the No. 1 thing respondents listed was community, and by an overwhelming amount.

Whether they talked about potlucks or shared worship experiences, peer and spiritual support, or even family, leaving Christianity comes at a steep price when regarding community, as people feel deeply alone:

- “I miss the community. I don’t have a single friend from my church days. It can get lonely.”

- “A localized gathering of likeminded individuals who support you. The connection with other Christians in your involvement at church/camp/etc. was a huge part of my life. Finding others who are in a similar position as you after deconstructing is like a breath of fresh air but is somewhat few and far between here in the Bible Belt.”

- “I don’t really feel like I can share my beliefs with anyone else, and my husband being an atheist makes me feel uncomfortable doing any form of worship in my home. So I bottle it all up inside and just generally feel awkward and alone all the time.”

- “A close-knit group of similar minded people. I think this is the reason so many stay in churches and that belief system. It’s all their friends and social network and too hard and lonely to change.”

- “I really miss the sense of community that I got from Christian church. I was able to wrap most of my life up in whatever church I attended. I not only attended Sunday services; I was in the choir, I did VBS, I was in every youth group I could be. As a young autistic kid who had a hard time making friends, it was so much easier to bond with people over a shared love of God and of church.”

After several months of reading responses like these again and again, my heart still breaks. There is a deep yearning for love in all these people — it’s the reason they leave Christianity; at times, it’s what they gain. But also, it’s what they’ve lost.

We, as a species, need love and belonging, and it’s evident in every one of these answers. And while Christianity is experiencing an exodus, it does offer some a level of satisfaction to these human yearnings. But at what cost? Ultimately, for many, the cost is too high to pay.

Brandon Flanery is a gay ex-pastor who has written for Baptist News Global, the Colorado Springs Indy, and the University of Colorado’s Scribe. He often writes about the intersection of faith and sexuality and is a signed author with Lake Drive Books. His debut book, Stumbling: A Sassy Memoir about Coming Out of Evangelicalism, released August 2023. Read and learn more about Brandon at BrandonFlanery.com.

Related articles:

These Christians are leaving behind the church, but not their faith | Analysis by Mallory Challis

Why I’m leaving my church: A theology of death | Opinion by Keith Hovey

‘Deconstruction’ is not a dirty word | Opinion by Andrea Huffman