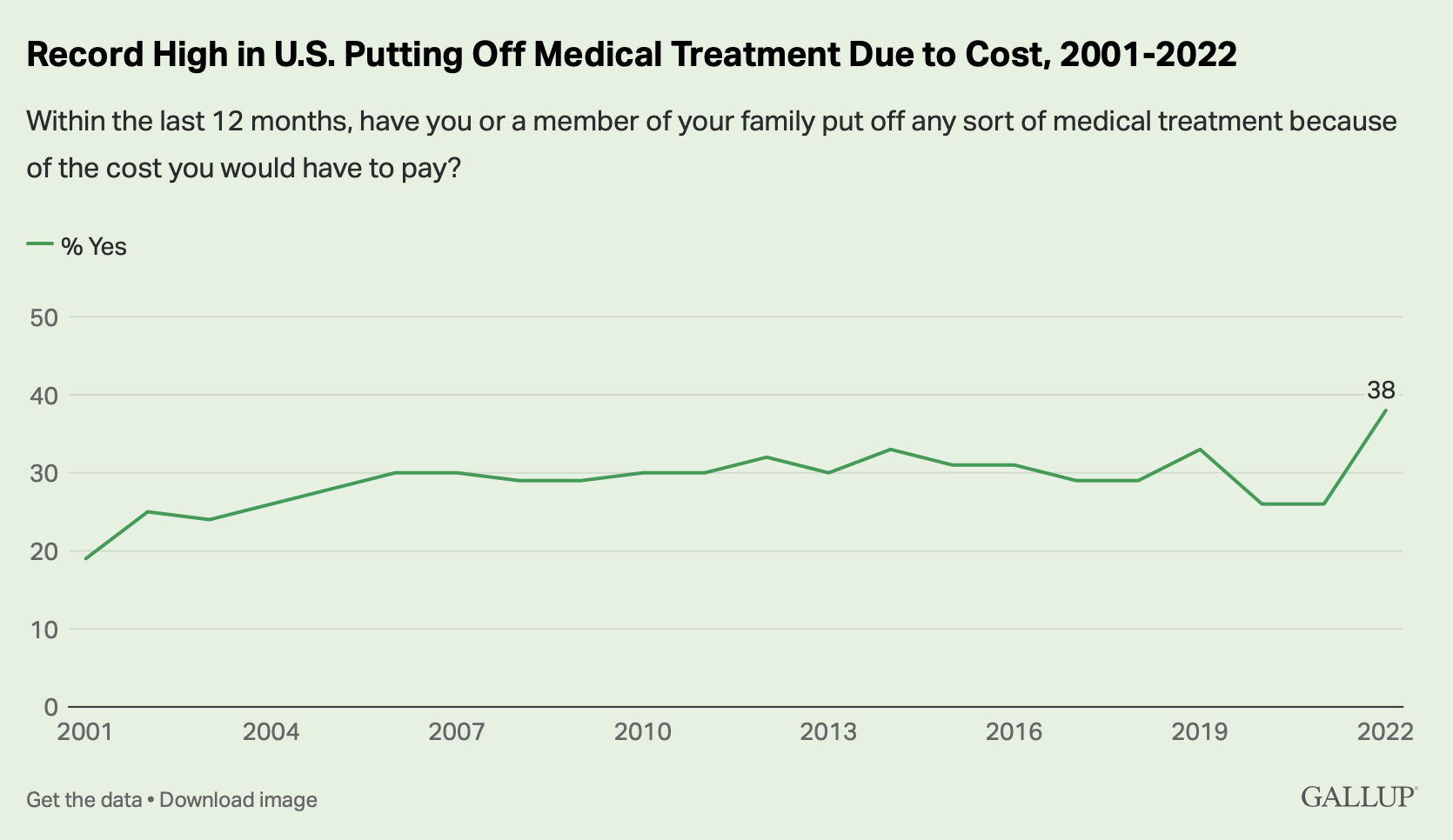

Imagine facing a medical condition and choosing to do nothing because of money. That was the case for 38% of Americans in 2022, up 12 percentage points from the previous year.

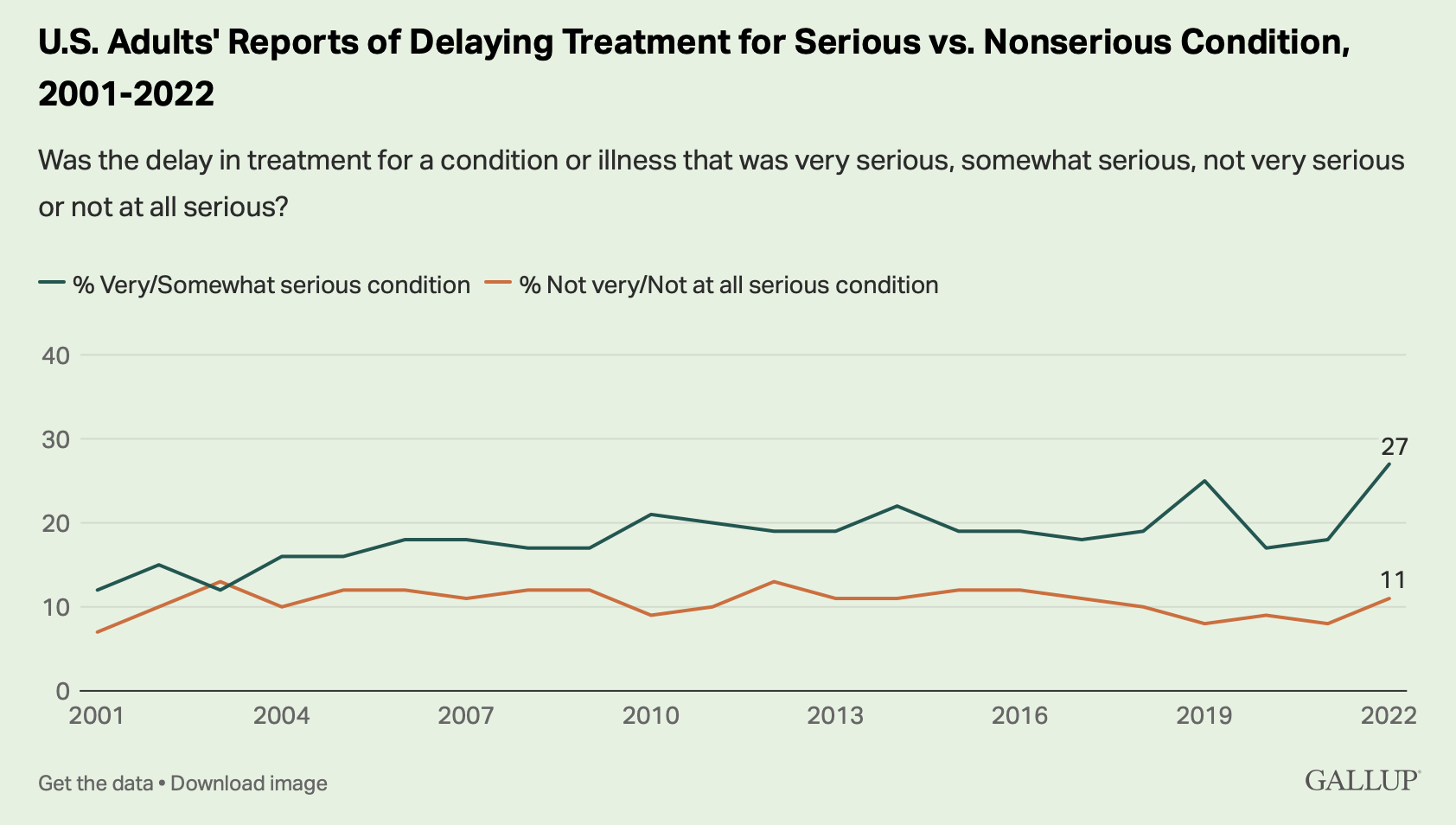

According to Gallup, 27% of Americans reported the medical issues they were putting off dealing with were somewhat to very serious.

As we sat on the hallway floor after we found out that my wife, Ruth Ellen, had stage three breast cancer in October 2021, I had many fears and questions. In addition to the fears and questions about her condition, I also wondered how I was going to care for her and for our five children, how we were going to survive financially, and how we were going to afford her treatments.

Doing nothing was not an option. And we had no idea what insurance would or would not cover.

A plight for poor families and women

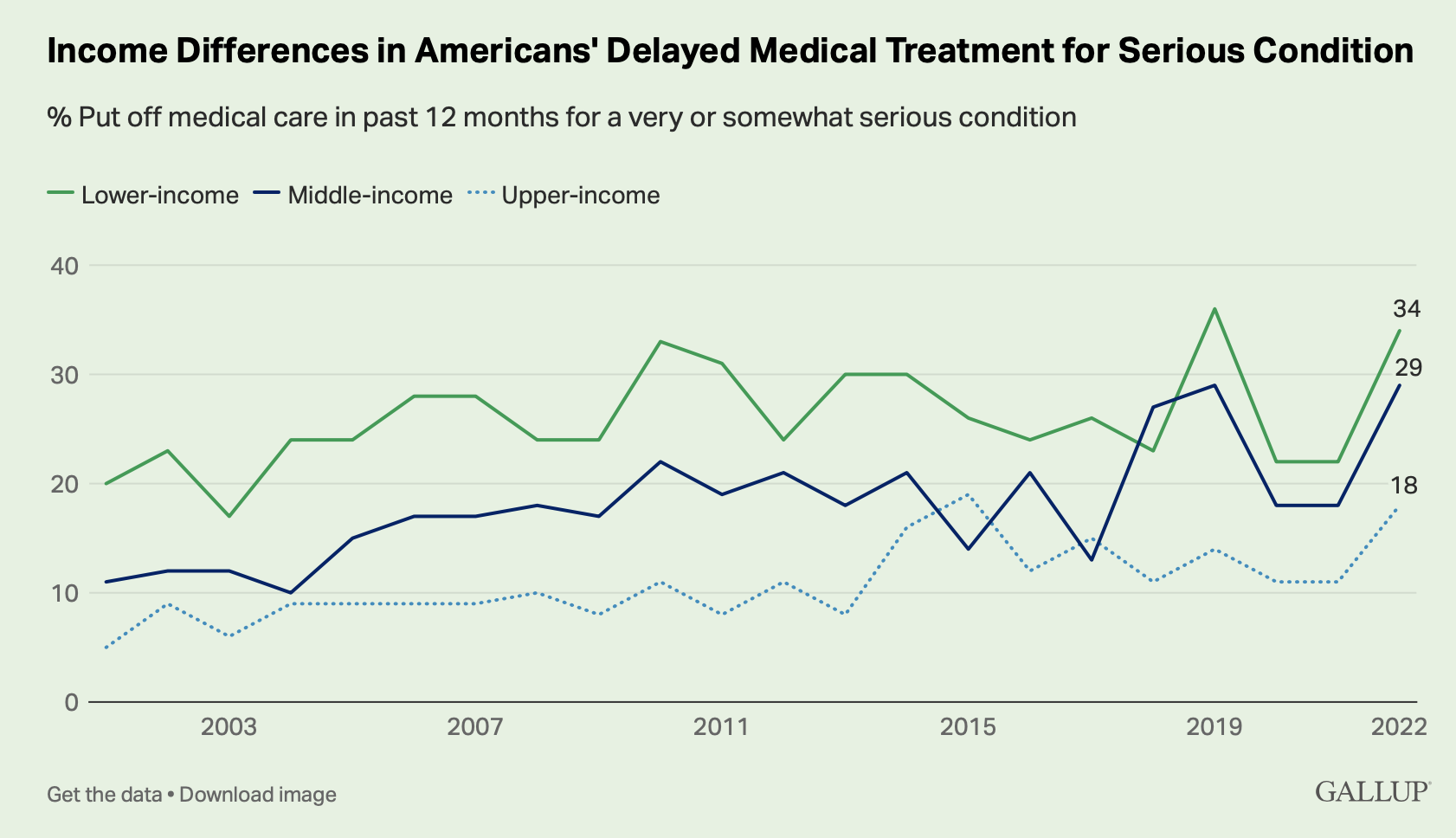

The problem of being able to afford health care is especially felt by families with lower incomes. According to Gallup: “Americans with an annual household income under $40,000 were nearly twice as likely as those with an income of $100,000 or more to say someone in their family delayed medical care for a serious condition (34% vs. 18%, respectively). Those with an income between $40,000 and less than $100,000 were similar to those in the lowest income group when it comes to postponing care, with 29% doing so.”

“A significant percentage of children have parents who are not receiving the medical care that they need.”

While many older people are covered by Medicare, younger families do not have that luxury. So while 13% of people 65 and older skipped treatment, 25% of those between ages 50 to 64 and 35% of people between ages 18 to 49 opted out. This means a significant percentage of children have parents who are not receiving the medical care that they need.

Gallup also found women were disproportionately affected, with 32% of women compared to 20% of men delaying treatment, which was “a 12-point increase from 2021 for women and a five-point increase for men.”

Playing the blame game

Because health care tends to be viewed primarily through political lenses in the United States, the question many want to ask is whether the Republicans or the Democrats are more to blame.

One obvious factor to consider is the influence of inflation on these numbers. With the rising cost of living, it makes sense that people would have financial concerns about how they might pay for the medical attention they need.

Republicans blame Democrats for inflation due to the stimulus packages that have been passed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and because it’s easy to blame the president who is currently in office for the problems currently happening. Democrats blame inflation on more complex global issues related to the pandemic and claim Republicans didn’t do enough to support those who need help the most and to hold accountable those who would take advantage of them.

But whoever is to blame for inflation in the years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic is to some degree beside the point. The trends going back to 2001 show the disparity between the wealthy and the poor, between the old and the young, and between men and women have been consistent the entire time.

In other words, our health care crisis cannot be reduced to blaming it on political opponents of the past few years. It has been going on for decades and the disparities along gender, race and class lines are getting worse.

The history of communal Christian hospitality

In his book Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity published by Johns Hopkins, Gary Ferngren explores what the earliest Christians believed about disease and healing. Even though the Bible contains stories about miraculous healing, Christians accepted the medical knowledge of the Greco-Roman world rather than hoping for miracles to heal them.

While the Greco-Roman practitioners had a growing understanding of medicine, scholars say they operated as individuals, moving from place to place attempting to make a profit. But when a pandemic came along, their individualistic, profit-driven approach to health care left them without adequate structures to care for people.

During the middle of the third century, the Roman Empire suffered from a pandemic that killed 5,000 people in Rome every day. Kyle Harper wrote in The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire that the city of Alexandria saw its population drop from 500,000 to 190,000 as a result of this pandemic.

“There is nothing remarkable in cherishing merely our own people.”

Despite the persecution Christians were under, the pandemic revealed their common suffering with non-Christians. As a result, Cyprian, who oversaw the church in North Africa, said to his church: “There is nothing remarkable in cherishing merely our own people.” Instead, he proposed that Christians “should love our enemies as well … the good done to all, not merely to the household of faith.”

Christians began to care for their non-Christian neighbors. And because they were organized communities, they were able to do so more effectively than individual traveling doctors. In a review published by the National Library of Medicine, Ildiko Csepregi wrote: “Christians’ long experience in medical charity prepared the way for the eventual establishment of the first hospitals as faith institutions. Christians were able to organize themselves well for a large-scale charity activity.”

Ferngren also noted the hospital was “in origin and conception, a distinctively Christian institution, rooted in Christian concepts of charity and philanthropy.”

As a result, the church began to grow, not by embracing the power of the empire, but by trusting the medical professionals and loving their neighbors as a community in the midst of a pandemic.

Baylor Hospital in Dallas as it appeared on a postcard in the early 20th century.

Christian and public hospitality for the poor

According to the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing: “A nursing tradition developed during the early years of Christianity when the benevolent outreach of the church included not only caring for the sick but also feeding the hungry, caring for widows and children, clothing the poor, and offering hospitality to strangers.”

This tradition continued through monastic communities in the Middle Ages, and then began involving universities through the Renaissance.

While the wealthy were able to afford medical care, including surgery, in their homes, the poor in the United States relied on isolation hospitals and almshouses beginning in the 1700s. But with the economic growth from industrialization and the professionalization of health care, the practice of medical care began taking place more frequently in hospitals.

A combination of Protestant and Catholic hospitals spread throughout the country, along with specialty institutions as medical knowledge continued to grow. But historian Rosemary Stevens wrote in “A Poor Sort of Memory”: Voluntary Hospitals and Government before the Depression that in the 20th century, “the hospital for the sick was becoming more and more a public undertaking.”

“Religious institutions were often the first ones built in these areas.”

“Other regional variations in hospital development reflected regional economic disparities, particularly in the South and West, where less private capital was available for private philanthropy,” the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing explains. “This hindered the creation of voluntary hospitals. Religious institutions were often the first ones built in these areas. Between 1865 and 1925 in all regions of the United States, hospitals transformed into expensive, modern hospitals of science and technology.”

After World War II, demand for hospital care rose as improvements in education and technology led to far more specialized services. The funding from individual citizens simply could not keep up with the costs. So the government had to provide more funding and oversight in order to ensure safe access to medical care for all.

With education, technology and medical care all converging together with their own profit motives, costs have continued to rise. The University of Pennsylvania has concluded: “Rising costs have forced many hospitals to close, including public hospitals that have traditionally served as safety nets for the nation’s poor.

A crisis of access to a wealth of resources

Households in the United States have 45% of worldwide gross financial assets, according to the Allianz Global Wealth Report of 2022. China is the second wealthiest at just 14%.

“The fact that in one of the richest countries in the world almost one third of the population belongs to the global low wealth class has not changed in the last two decades.”

But despite the wealth concentration in the United States, the discrepancy of resources is unparalleled in the world. The Allianz report says: “In hardly any other rich country is the distribution of wealth as unequal as in the U.S. … The fact that in one of the richest countries in the world almost one third of the population belongs to the global low wealth class has not changed in the last two decades.”

According to Forbes, the average American pays between $313 and $1,225 monthly for health insurance, depending on age, deductible and plan. Many families are paying more than $1,000 a month. Ironically, these are the plans under the Affordable Care Act.

It makes sense then that 38% of Americans would put off medical treatment due to concerns about the cost.

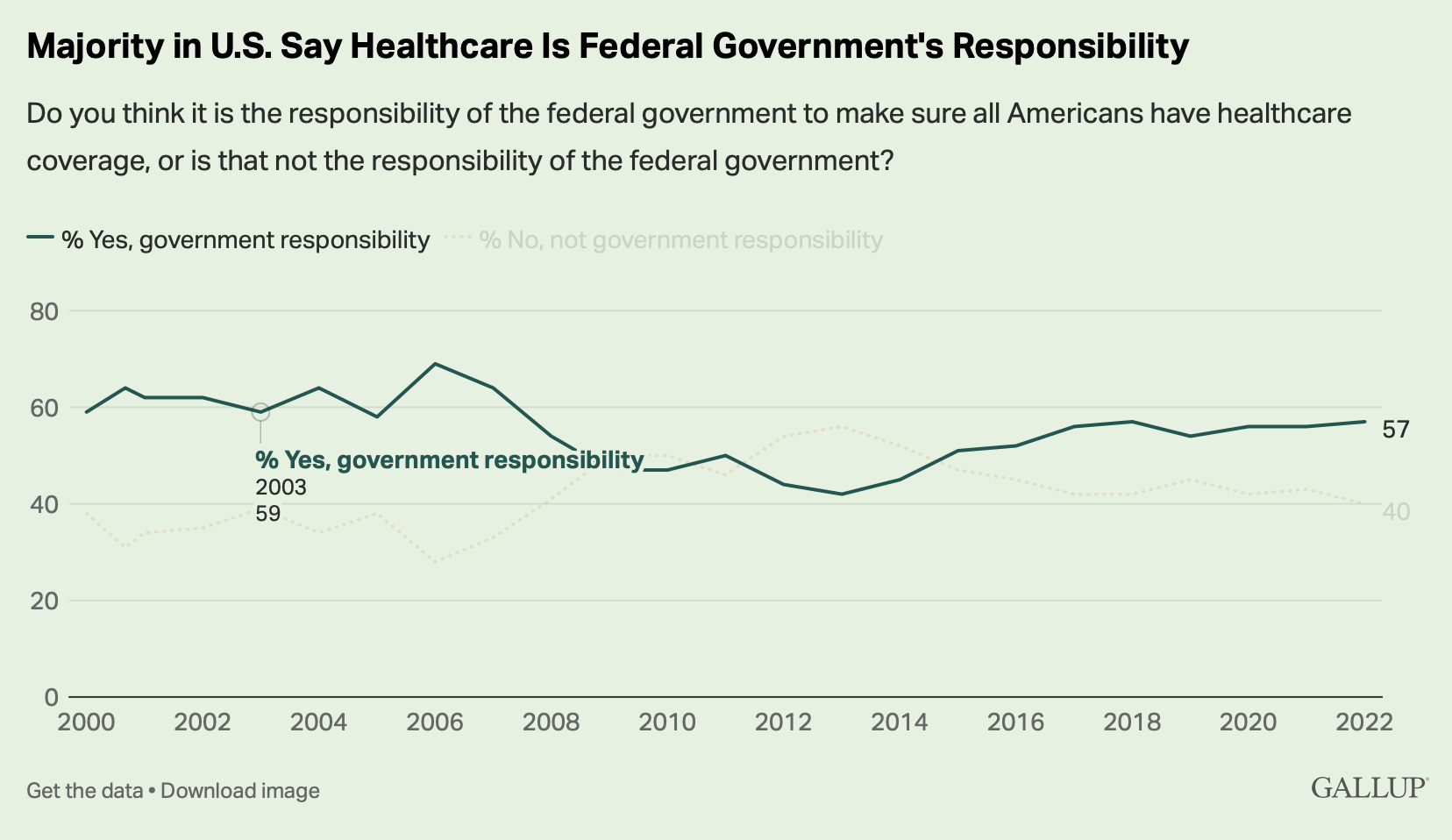

Meanwhile, another Gallup poll found while 57% of U.S. adults believe the federal government should ensure all Americans have health care coverage, nearly as many (53%) prefer the U.S. health care system be based on private insurance only.

Gallup summarized: “Americans continue to hold a nuanced view of the U.S. health care system, with a majority saying the government should ensure that all Americans have coverage but preferring that the system be funded privately. Partisans have fundamentally differing views on how health care should be delivered in the U.S., with Democrats indicating support for a system where the government not only guarantees coverage but provides health care, while Republicans remain wedded to the current system of private coverage and health care.”

Howard Thurman’s communal ethic of Jesus

The heart of the gospel in its earliest form, according to Jesus, is “good news to the poor … release to the captives … sight to the blind … (freedom to) those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Jesus’ mission described in Luke 4 was about God’s favor in the cultivating of human wholeness through physical healing and the removal of financial debt for neighbors.

Howard Thurman, who spoke of “the religion of Jesus” as an alternative to empirical Christianity, discussed this ethic for communal wholeness in The Search for Common Ground.

Howard Thurman (Photo: Boston University photo services)

“If the mind of man has an affinity with the world external to him, and if in his origin and continuity he is a child of nature, then the experience of being consciously in touch with other forms of conscious life around him is a vital part of all life that seeks ever to realize itself in its many forms,” Thurman wrote. “When men ignore this, then their behavior very easily becomes wantonly destructive, and in their blindness, ignorance or arrogance they force expressions of life around them to fall short of actualizing their potential. In the extent to which this takes place, community itself is defeated in the life all around us. If this is done, it may be that man himself is cut off from actualizing his potential and thus cannot know community in himself and in the world of his fellow.”

One way we help our fellow humans actualize their potential is through freeing them from what is holding them down. In the United States, 38% of our neighbors have delayed medical treatment due to the financial costs involved.

Of course, I am not an expert in economics or health care. But I know enough to say that far too many of us are falling short of actualizing our potential because we’re too financially strapped from an individualist, profit-driven health care system to seek the medical attention we need.

Connecting through our common human suffering

In an article for the Journal of Religion and Health titled “An Exploration of Suffering and Spirituality Among Older African American Cancer Patients as Guided by Howard Thurman’s Theological Perspective on Spirituality,” Jill Hamilton and Walter Fluker wrote: “Thurman’s theology also proposes that all individuals strive for a sense of community through harmonious relationships with others. Individuals make conscious deliberate choices to strive for wholeness and harmony and integration within themselves, others and the world. Specifically, Howard Thurman’s conceptualization of ‘common ground’ was his quest for community.”

During this past year in our family, Ruth Ellen has undergone chemotherapy, multiple surgeries, and radiation treatments. In November, we celebrated her becoming cancer free by throwing a party for all the people who helped us during that year. As we gathered together under the glow of the lights in our friends’ backyard that evening, I noticed how much diversity was there. Both Republicans and Democrats came together to help us. Everyone from conservative evangelicals to agnostics and atheists gave of themselves to bring us food, clean our house, watch our kids or simply offer friendship.

“Despite our profound differences across religious and political lines, we came together in our common human suffering to help a neighbor in need.”

Despite our profound differences across religious and political lines, we came together in our common human suffering to help a neighbor in need.

When Ruth Ellen was fighting just to stay awake and I was trying to take care of her and the kids, the last thing we needed to do was to compete in the most economically imbalanced health care system in the world against insurance companies that feed on profit. We needed to focus on ourselves, and we needed community to help us survive.

Wholeness, communism and community

For Christians to pursue Jesus’ mission of embodying God’s favor through the cultivation of human wholeness, we need to do more than touting the Christian history of starting hospitals as a way of washing our hands of our responsibilities today. We need to stop ignoring the ethic of Jesus and Christianity’s history of social concern by labeling any attempt to care for our neighbors in community as communism. We can’t be so afraid of communism that we disembody ourselves from community.

Instead, the challenge for Christians today is to reflect on what Jesus proclaimed, and to remember how Christianity has responded throughout history to pandemics through communal health care for all.

Many stories today are being told about the harm Christian communities have caused for their neighbors throughout history. And those stories must be told. But the story of how Christians have come together amidst pandemics and health crises throughout history to help their neighbors is one we can look back on as a positive example to learn from.

We also need to recognize the capitalistic beast of American health care has gotten far too big for us to compete in as individuals. But by remembering where we’ve been, and by becoming aware of the injustices in our profit-driven health care market today, perhaps we’ll have a better perspective on how we can love our neighbors toward human wholeness today.

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

Health care crises reveal our nation’s character flaws | Opinion by David Gushee

Caring for the casualties of a broken health care system | Opinion by Beth Jackson-Jordan

How a Baptist educator and businessman’s simple plan gave rise to the health insurance industry