Participating in the racial integration of Mercer University was not for the faint of heart when the process began in the 1960s, said Pearlie Toliver, one of the first Black women to attend the Macon, Ga., institution.

Toliver, who also was among the first African American students to integrate local public schools in Macon, delivered Mercer’s Feb. 1 Founder’s Day address marking the 60th anniversary of the university’s integration under the leadership of then-President Rufus Harris and Mercer’s board of trustees.

Pearlie Toliver

While rewarding at times, becoming an undergraduate at Mercer in 1965 also demanded courage, Toliver said in her address. “To say these were dangerous times is an understatement. The integration of Mercer and the public school system was not appreciated by all in the community, as you would suspect.”

Toliver said she was honored to be invited to speak at the observance but also admitted to struggling with how to express gratitude for the university’s positive impact on her life while relaying some of the challenging episodes of integration.

She explained “How do I share this college experience? How do I share without sounding bitter? How can I be uplifting to the students? How can I positively share my personal pain and disappointment with strangers? I found the answer in the words of Charles Dickens: ‘It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.’”

Change began in September 1963 when Cecil Dewberry, Bennie Stephens and Sam Oni become the first Black students to take classes at Mercer, the university reported in a racial integration timeline. That year, Mercer and Emory University in Atlanta became the first two private universities in Georgia to voluntarily integrate.

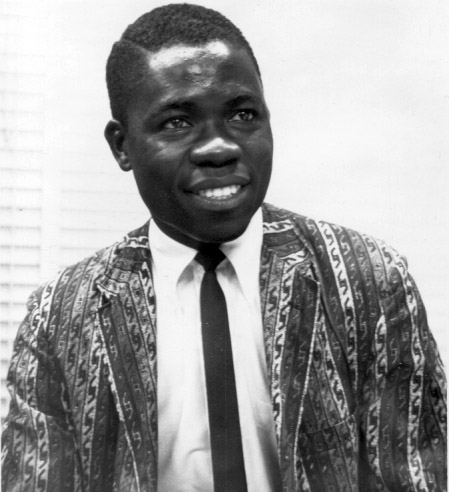

Sam Oni

It wasn’t easy. Upon graduating in 1967, Oni, a native of Ghana, vowed “to never return to Georgia again due to the difficulties he experienced while in Macon, primarily in the religious community.”

Even with the support of Harris and many faculty members and administrators, opponents of integration made their feelings clearly known, Toliver said.

“I remember repeating to myself over and over again: ‘I have the right to be here. I have the right to be here. I have the right to be here.’”

“Can you imagine the unbelievable mental pressure? It was scary. I can remember the day we met President Rufus Harris. I remember walking through the line to shake his hand, and I remember repeating to myself over and over again: ‘I have the right to be here. I have the right to be here. I have the right to be here.’”

Toliver said she was helped through the experience by Mercer faculty members who had been involved in guiding the integration of the Macon-Bibb County School System in 1964, beginning with the 12th grade.

“This was the start of my first personal interaction with Mercer University,” she said. “Realizing it would be a tremendous challenge to integrate (the public school), several professors from Mercer University … worked with the Black leadership to facilitate this experiment in social and educational change. These individuals played a vital role in accomplishing a smooth transition. They held meetings with us and really tried to make this historical transition as smooth as possible.”

“This was the start of my first personal interaction with Mercer University,” she said. “Realizing it would be a tremendous challenge to integrate (the public school), several professors from Mercer University … worked with the Black leadership to facilitate this experiment in social and educational change. These individuals played a vital role in accomplishing a smooth transition. They held meetings with us and really tried to make this historical transition as smooth as possible.”

It also helped that Toliver’s older sister and longtime Mercer snack bar manager Thelma “T-Lady” Ross was universally revered by administrators, faculty, staff and students at the historically Baptist University.

With integration, Ross became an immediate ally and comfort to Black students adjusting to campus life, Toliver said. “She was always there for us, as she was for every student who walked through those doors. She called us her ‘young’ns.’ We were young, and she was indeed the mama bear.”

Another inspiration was the late Francis Otto, then dean of chapel at Mercer. His weekly talks to students helped her through to graduation in 1968 and well beyond.

“He would say, ‘In order to be successful, you have to know who you are, where you are and where you are trying to go.’ Now, that was more challenging to me than any class I took. It frustrated me for years. But it has been the guiding light for me through life. Therefore, I challenge you today to know who you are, where you are and where you’re trying to go.”

Pearlie Toliver with Sam Oni

Studies at Mercer gave way to a career in retail banking and mortgage lending that included collaborating with the university, government agencies and nonprofit groups to racially and economically revitalize numerous Macon neighborhoods, Toliver said.

With a nod to current Mercer President William Underwood sitting nearby, Toliver concluded with a recitation of the university’s mission statement pledging to educate students to live successful and full lives and to inspire them to become leaders.

“President Underwood, as I have been forced to look at my life over the last few days by you, I can honestly say in my case: Mission accomplished. Thank you for allowing me to stay connected with Mercer.”

Related articles:

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

‘Listen before you preach,’ Godsey says at McAfee Founders Day