In 2010, I arrived for my interview with an educator. Brushing raindrops off my tan trench coat, I was directed to a room where several folks were seated. This panel would determine if I’d be a good match as their editor.

Looking from left to right, I noticed all were Black. I am white. For a brief moment, this new experience gave me a fleeting, unfamiliar sense of awareness.

Phawnda Moore

Rex Fortune’s professional demeanor was calming. To begin, he modestly outlined his lifelong dedication to successful leadership in education. He proudly introduced his team, explaining their roles for a research project that would become his first published book.

It begged the question: “How can low-achieving minorities close the achievement gap?”

To illuminate the way for change, the Fortune team had studied 20 K-12 schools and then traveled around California to personally interview administrators, teachers and parents who shared his dream.

I, in turn, introduced myself as the editor for the California Community Colleges chancellor’s office. I wrote grants and our divisions’ reports to the Legislature, where I served in the communications department.

It was a good meeting. Our two worlds connected for one purpose — the common vision of what education could be, should be. I left with the assurance that Fortune embraced everyone he met with respect and fairness. I was thrilled to be selected for the position.

More than two years later, it was my pleasure and honor to place the 512-page book, Bridging the Achievement Gap: What Successful Educators and Parents Do in his hands, saying, “You are a published author.”

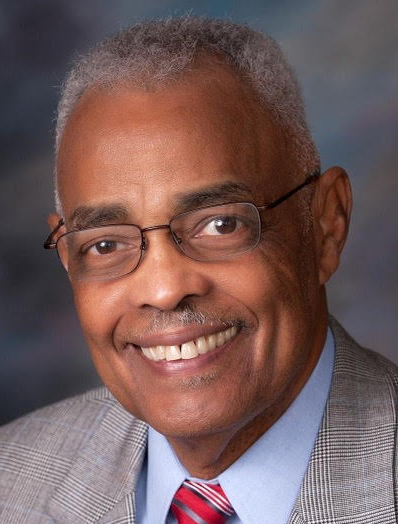

Rex Fortune

Fortune didn’t intend for me to learn about discrimination, but how could I not. I’d attended all-white schools and met my first Black student in high school; she was the foreign exchange student. I lived in a predominantly white neighborhood and community.

I hadn’t thought there was a race problem in education or anywhere else, but here was clear evidence to the contrary.

Fortune cited one of the nation’s leading advocates in the field of education, Kati Haycock, early in his book to define how the achievement gap affects minorities. For every 100 students, 49 Asians obtain at least a bachelor’s degree compared to 30 for white students, 16 for Black students, and six for Latino students. In addition, Black students also face unemployment and/or lower income and incarceration as a direct consequence.

Here’s one explanation of the situation: “Achievement gaps in the United States are observed, persistent disparities in measures of educational performance among subgroups of U.S. students, especially groups defined by socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and gender. The achievement gap can be observed through a variety of measures, including standardized test scores, grade point average, dropout rates, college enrollment, and college completion rates. The gap in achievement between lower income students and higher income students exists in all nations and it has been studied extensively in the U.S. and other countries, including the U.K.”

Administrators, educators and parents acknowledge the achievement gap is a tragedy of America.

And finally, so did I.

I began to see things differently; I read articles and joined a church group about race. We had conversations about Jim Crow laws, segregation, slave escapes and more. Most of us did not learn much about Black American history at all in school.

I could not have imagined the injustices a Black person experienced — then or now — without their powerful, personal stories.

Fortune’s questions and more were still being explored years later. Christina A. Samuels, in her article, asked: “Who’s to blame for the Black-white achievement gap?” One matter is funding. “Right now, majority-minority school districts get $23 billion less in funding nationally than majority-white school districts, according to EdBuild, a nonprofit organization working to overhaul school finance systems.”

“Why achievement gaps exist is an important question. But more to the point, I think, is that we agree that we are all responsible for trying to close them.”

Samuels continues: “So why are achievement gaps so persistent? I’m left with the realization that none of us are off the hook. Not parents, teachers, schools or policymakers. I have a son who is just a few years into his public school education. Like my parents did for me, I’d like to create a path so smooth that he is successful without even having to think too hard about how it happened. But I can’t do it by myself, no matter what my SAT scores were. Why achievement gaps exist is an important question. But more to the point, I think, is that we agree that we are all responsible for trying to close them.”

Beyond awareness, the next step is being responsible to enact change. Can we do it? Will we do it?

During the next decade, Fortune continued his work quietly and with purposeful energy. We produced a series of parenting books in English, Chinese and Spanish. He was excited about these “little” books, a much lighter assignment than before. “Can you paint a bird?” he smiled. “I just want a little bird on the cover.” Of course. I chose a robin which is said to symbolize happiness and following one’s dreams.

On occasion, we exchanged cards and emails. He supported my own books and awards with kind, funny and encouraging words. It was a sad moment, days before Black History Month began, to learn he had passed away.

I was surprised to read that he recently shared more personal experiences from his childhood in the South. The Sacramento Observer reported: “It was when Dr. Fortune’s father asked him to erase the names of white children from textbooks sent to Black schools when he began to realize segregation was separate and unequal. ‘Do you think our science books had the same information as the new science books being sent to the white schools?’ he reflected.”

I realized Fortune’s legacy continues to make achievement possible for all. This fall an elementary school bearing his name will open. A ground-breaking photo shows smiling, young Black students saluting him, and he is returning the love, beaming back. This was the essence of his life.

“What many underestimate is the impact of Black teachers,” he said, his voice breaking as he reflected on his own childhood. “They said — while we may not have everything — we could be anything we wanted to be.”

His life modeled that, not only for himself, but for others. As he said in Bridging the Achievement Gap: “Please know that our young people need your initiative, courage and thoughtful steps toward a promising future.”

We can be anything we want to be. Thank you for living your vision, Dr. Fortune.

Phawnda Moore is a Northern California artist and award-winning author of Lettering from A to Z: 12 Styles & Awesome Projects for a Creative Life. In living a creative life, she shares spiritual insights from traveling, gardening and cooking. Find her on Facebook at Calligraphy & Design by Phawnda and on Instagram at phawnda.moore.