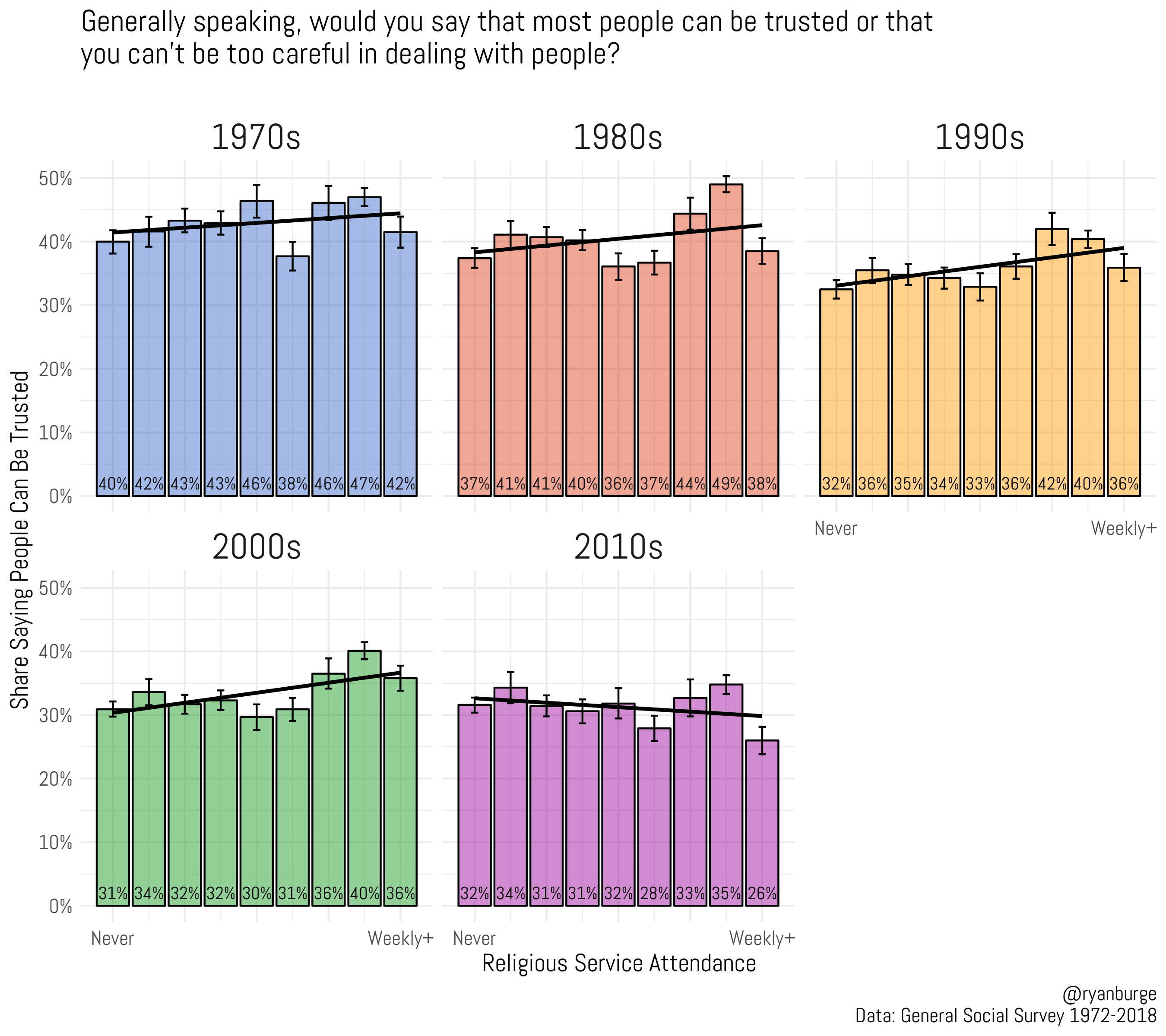

On March 8, statistician, pastor and author Ryan Burge tweeted a series of graphs showing responses from survey participants sorted by varying frequencies of religious service attendance. Participants answered the question, “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”

The graphs demonstrate that religious service attendance was positively correlated with increased levels of interpersonal trust in each decade from the 1970s until the 2000s. However, in the 2010s, a reversal occurred. During this decade, as the frequency of religious service attendance increased, levels of interpersonal trust decreased, with only 26% of weekly church attendees saying, “People can be trusted.”

Political polarization among church congregations may be the culprit here.

According to data from Pew Research Center, more Republicans than Democrats attend religious services at least once per week (44% vs. 29%). Pew Research Center’s data also show that in general, a greater share of Republicans are Christians compared with Democrats, although both parties do have a majority representation of Christians (82% vs. 63%).

When asked to interpret the data, Burge said increased levels of polarization between people of different political identities play a huge role in this lack of interpersonal trust. Burge called this an “increased homogeneity among weekly attenders,” as Republicans attend weekly a third more often than Democrats.

“High attenders are predominantly Republicans now,” he said. “Conservative folks, by and large, hold to a more individualistic view of the world.”

Because of this individualistic worldview, he explained, cooperation becomes hard. Conservatives believe Democrats — who often do not hold this worldview — are unlike them and should not be trusted.

This makes for politically segregated congregations, as both conservative Christians and more liberal Christians often choose to attend churches they think align with their political affiliations. That means they increasingly do not often intermingle with the opposing group.

“They may not even know a liberal person anymore.”

“What makes that worse is the fact that so few liberals/Democrats are sitting in the pews next to (conservatives/Republicans) each week. So, they may not even know a liberal person anymore,” Burge said. “And that’s a bad thing. The social contact theory says that ‘intergroup contact under appropriate conditions can effectively reduce prejudice between majority and minority group members.’”

However, because politically conservative and liberal Christians are not interacting with each other on a regular basis, let alone having conversations with one another, prejudice is growing and assumptions they should not trust one another are being affirmed.

“So, no bridge building between those distrustful conservatives and liberals. And in the absence of relationship development, humans tend to create caricatures of the other side,” Burge said.

This is not a new trend but has become more extreme in recent years.

In his 2018 article, “Democrats Are Wrong About Republicans. Republicans Are Wrong About Democrats,” Perry Bacon Jr. discussed how many Americans divide themselves politically based on “negative partisanship” rather than personal beliefs. People identify themselves within a certain party not based on their own political alignments, but on how much they dislike the opposing party, Bacon said, reporting 40% of both Democrats and Republicans do this.

However, most Americans’ views of the political parties they do and do not belong to are wrong, he added. According to a study by Douglas Ahler and Gaurav Sood published in the Journal of Politics, when Republicans and Democrats are asked demographic questions about the opposite party, they get the answers wrong, usually by a large margin of error. So, the biases Americans hold against others based on their political affiliation are not as accurate as often assumed.

For both Democrats and Republicans, partisan identity has become a “mega-identity.”

Political scientist Lilliana Mason, in her book Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity, says for both Democrats and Republicans, partisan identity has become a “mega-identity” because it not only describes political preference but also describes other aspects of identity that are socially associated with that party, even non-political ideals such as sexuality, race or religion.

For example, it is more likely that someone who identifies as a Democrat will be assumed to be part of or in alliance with the LGBTQ community, while it may be assumed someone who identifies as a Republican will not. But this is not always true.

Still, research also shows that after joining a political party, many Americans subsequently change their views to conform to what they perceive that party’s identity to be.

For example, polls asking both Democrats and Republicans about their opinions on Vladimir Putin each year from 2014 until 2017 showed little change in the number of Democrats who viewed him favorably. However, after the 2016 election of Donald Trump as president of the United States, there was a big change in Republican attitudes. Pollsters found an increase of 13 percentage points in Republican favorability for Putin between September 2016 (before the U.S. presidential election) and December 2016 (after the election).

These three factors — “negative partisanship,” the “mega-identity” and conforming to perceived partisan views — cause Americans to become more politically polarized.

As more Christians segregate themselves (and completely avoid each other) by political affiliation, they begin to view Christianity as part of their own political mega-identity.

Correspondingly, because they are only interacting with those in their party and never those outside, conformity to their own party increases and biases against the other party become progressively stronger.

That, in turn, leads to assumption that their party is associated with “good” and “Christian” things while the other party is not.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

Conservative or liberal? Jesus widens our political landscape | Opinion by Russell Waldrop

Social liberalism grows while economic conservatism still dominates