Since the 2016 election, pundits, preachers and politicians have been asking why more than 80% of white evangelical voters threw their support behind the most corrupt, ill-informed, vulgar and intentionally divisive politician in American history.

Gradually, a consensus emerged. Donald Trump won over white evangelicals by giving them exactly what they wanted.

A transgressive political strategy

Since the Democratic Party embraced the Civil Rights movement in the mid-1960s, Republican politicians have made room in their big-tent coalition for white evangelical Christians. While big donors provided the funding for the conservative movement, the reasoning went, white pro-life evangelicals would supply the grassroots passion.

White evangelical pastors and opinion leaders weren’t always happy with this arrangement, but it was the best deal on offer. Republicans talked a good game on abortion and adopted conservative stances on sexual issues, but nothing changed. White evangelicals felt manipulated, patronized and taken for granted.

After listening to the complaints of white evangelical leaders, Trump saw his opportunity. If he could win the support of working-class white evangelicals in the South and Midwest, the conservative movement would be forced to fall in line. He was right.

Initially, the Republican establishment was horrified by Trump’s candidacy. Fox News was less than enthusiastic. But the base loved him, and their support didn’t waver in the wake of the Access Hollywood tape, the Mueller probe or the Ukraine bribery scandal. Even a failed insurrection didn’t dampen their enthusiasm.

“If Lincoln appealed to the better angels of the American spirit, Trump unleashed the demons.”

It wasn’t enough to champion the stated interests of his base, Trump realized; to win abiding loyalty he needed to insult and ridicule the opposition. White evangelicals weren’t simply willing to overlook his transgressive behavior; they positively reveled in it. Every bleat of outrage from the Left enhanced his credibility in their eyes. If Lincoln appealed to the better angels of the American spirit, Trump unleashed the demons.

There was a downside to this strategy, of course. By the end of his presidency, Trump’s sophomoric sadism had earned the scorn of mainstream media, Hollywood, SNL, late-night comedians and a solid majority of non-white voters. Privately, Fox celebrities like Tucker Carlson were eager to ditch Trump and move on. Mitch McConnell, the second most powerful man in Republican politics, was finished with the former president.

Trump’s white evangelical base didn’t budge. And it wasn’t long before Kari Lake of Arizona, Ron DeSantis of Florida, Greg Abbott of Texas, and Republican-controlled legislatures across the nation were photocopying pages from Trump’s playbook.

C.S. Lewis Republicans find their voice

A small but intrepid band of Never Trump Republicans has become increasingly outspoken. Just listen to Charlie Sykes on the Bulwark Podcast and you’ll see what I mean. Never Trump evangelicals are equally unrestrained. Check out The Holy Post Podcast and listen to Skye Jethani, Phil (Veggie Tales) Vischer and Kaitlyn Schiess express their dismay with the evangelical world. Russell Moore, who recently left the Southern Baptist Convention to become editor in chief at Christianity Today, uses The Russell Moore Show to map out a more loving, rational and compassionate expression of evangelicalism.

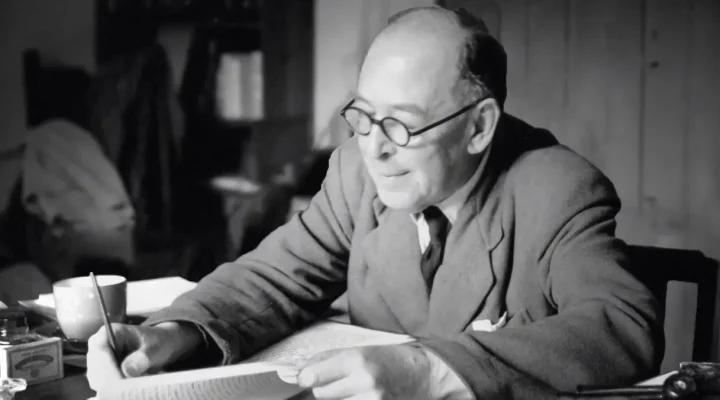

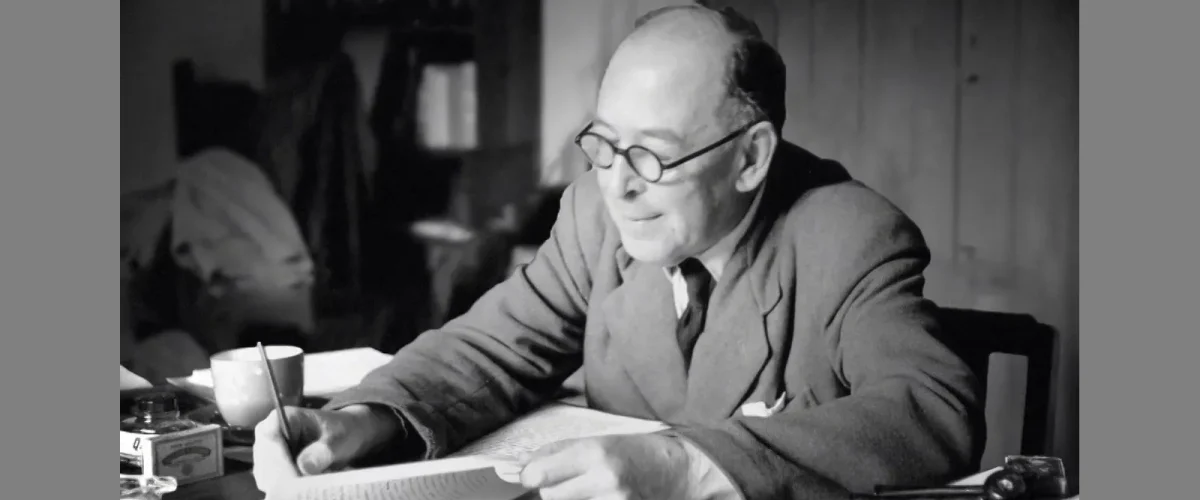

I call these people C.S. Lewis evangelicals. They are always quoting the British author who breathed his last six decades ago. And even when they don’t drop his name, they share his perspective. Watch the Russell Moore Show and you will see a portrait of Lewis just over his left shoulder. Having been a big Lewis fan in my younger days, I recognize his voice when I hear it.

Lewis in a nutshell

A respected professor of English literature at Oxford and Cambridge, Lewis was essentially a popularizer who, when writing for a popular audience, avoided academic jargon. In children’s books like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, works of science fiction like That Hideous Strength, and mercifully brief works of popular theology like The Screwtape Letters, Lewis bristled with elegant grace.

Ideologically and theologically, Lewis was a traditionalist who saw human beings as tragically fallen yet called to radical sanctification. He despised “chronological snobbery,” the notion that modern progress has rendered irrelevant the moral ideals of past generations.

Lewis had little patience for the pompous posturing of an academic culture that, in his view, had foolishly dispensed with God. But he also cautioned that “every intrusion of the spirit that says ‘I’m as good as you’ into our personal and spiritual life is to be resisted just as jealously as every intrusion of bureaucracy or privilege into our politics.”

A confirmed monarchist, Lewis argued that when “men are forbidden to honor a king they honor millionaires, athletes or film stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.”

One shudders to think what Lewis would have made of a self-promoting charlatan like Donald Trump.

But Lewis never appealed to an inerrant Bible, he realized the universe was very old and very big, and he respected scientific authorities (so long as they confined themselves to their field of expertise). He didn’t pretend to be a theologian, a philosopher, and confined himself to “mere Christianity,” the small corpus of basic teaching most Christians have affirmed through the ages.

Lewis believed in the ultimate triumph of God, but he didn’t see it coming through human effort. He was uncomfortable with the penal-substitutionary theory of the atonement, he believed non-Christians could be saved, and he saw hell as God’s ultimate concession to free will.

Inerrantists in name only?

In America, most C.S. Lewis evangelicals do affirm biblical inerrancy, while admitting the Good Book can be used to prove just about anything. The rhetoric of biblical inerrancy is their way of affirming a high view of biblical authority.

In a recent interview with Russell Moore, Rick Warren, a megachurch pastor recently ejected from the Southern Baptist Convention, distinguished between “conservative” Christians who believe in the inerrancy of Scripture, and “fundamentalist” Baptists who believe in “the inerrancy of their interpretation.”

Warren insisted his recent decision to ordain women to pastoral ministry was driven by the clear teaching of Scripture. In a recent column in Christianity Today, Moore acknowledged that “many of us are rethinking who we once classified as ‘enemy’ and ‘ally.’” It is possible, he concluded, that “the lines of division were in the wrong places all along.”

Although Moore is frequently criticized for having “gone liberal,” his views on many issues have a distinctly conservative ring. He believes same-sex attraction isn’t sinful in itself but still insists gay Christians must remain celibate. I fully suspect Moore will eventually change his mind on gay inclusion just as he has evolved on the role of women in the church.

Forging a new kind of conservatism

C.S. Lewis evangelicals straddle the line between politics and religion. Pundits like David Brooks, Peter Wehner, David Frum, Michael Gerson and David French speak of Trump Republicans and white evangelicals as if they comprised a single group. Once influential Republican operatives, these men have been cast out of their political tribe. Since white evangelicals were largely responsible for this shift, their tendency to speak of religion and politics in the same breath is understandable.

Evangelical women like scholars Kristin Kobes Du Mez and Beth Allison Barr recently have emerged as critics of a male-dominated white evangelical world. Beth Moore, a bestselling author and popular speaker, recently joined the revolt.

“Having lost their place in conservative Christian culture, C.S. Lewis evangelicals are forging new relationships and creating fresh networks.”

Having lost their place in conservative Christian culture, C.S. Lewis evangelicals are forging new relationships and creating fresh networks. In the process, they may be fashioning a new kind of conservative Christianity.

Carving out a new middle

When I listen C.S. Lewis evangelicals decrying the great American culture war, I am reminded of a line from an old ’70s song: “Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right, here I am, stuck in the middle with you.”

Remaining true to Jesus, in their view, means rejecting the “extremist positions” peddled on both sides of the ideological divide. Never Trump Republicans speak glowingly of a center-right, center-left coalition. C.S. Lewis evangelicals appear to be looking for something similar in the theological-moral arena.

But C.S. Lewis evangelicals are primarily worried by the “jokers to the right.” Being rejected by your spiritual tribe can be profoundly traumatizing, almost like being disowned by your mother. So, it is natural for them to work through their grief out loud.

Besides, most of the hostility directed toward C.S. Lewis evangelicals on social media comes from the right, if only because these folks are rarely picked up by liberal radar. Secular Democrats associate “evangelicals” with Trump, gun culture and Christian nationalism, and, on most big issues, C.S. Lewis evangelicals sound a lot like center-left Democrats. They believe in racial justice, religious liberty for all faiths (and people of no faith), and (with a few exceptions) compassionate immigration and economic policies. Ostensibly pro-life, they are increasingly uncomfortable with the punitive laws currently being passed by Republican legislatures.

“The Republican Party and white evangelicalism have both been crippled by a catastrophic brain drain.”

The Republican Party and white evangelicalism have both been crippled by a catastrophic brain drain. By now, anyone refusing to accept a status quo that grows more bizarre by the day has been jettisoned. Those who remain either glory in the madness or they have gone mute. No one is left to stem the lemming stampede.

“The scandal of the evangelical mind,” Mark Knoll opined in 1994, “is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.” Knoll was right, but not because evangelicals of the period lacked intelligence or insight; most of them were simply too cowed to think or speak freely.

I am confident C.S. Lewis evangelicals will continue to evolve on theological and ethical issues. No longer subject to extremist backlash, they will be free to consider fresh options. Gradually, cautiously, C.S. Lewis evangelicals are speaking up. We should listen in. We just might learn something.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He lives in Fort Worth, Texas, and is a member of Broadway Baptist Church there.