Deborah Birx knows how to solve America’s rural health care crisis, and it involves faith leaders and congregations. How does she know? Because she fixed Africa’s rural health care problem during the height of the AIDS pandemic, relying every step of the way on faith communities.

Birx, now a senior fellow with the George W. Bush Institute, led President Bush’s signature aid program, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, as an ambassador to dramatically reduce HIV/AIDS infections in developing countries. She went on to lead the U.S. response to COVID, as the White House coronavirus response coordinator, working to reduce deadly infection in a health care landscape that in some ways is weaker, she says, than the services in sub-Saharan Africa during the height of AIDS infections.

Ambassador-at-Large Deborah L. Birx, M.D., Coordinator of the United States Government Activities to Combat HIV/AIDS and Special Representative for Global Health Diplomacy, testifies before a U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing to urge critical support in the global fight against HIV/AIDS May 6, 2015, in Washington, D.C. She is accompanied by Sir Elton John. (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images for EJAF)

PEPFAR is a $100 billion program that targets countries with high infection rates, largely active in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. According to the State Department, by helping countries control HIV spread, PEPFAR saved 25 million lives, prevented millions of HIV infections and strengthened health security for the entire globe.

The secret to PEPFAR’s success, Birx says, is community connections on the ground, and often the nexus for the community is a church or mosque. As PEPFAR celebrates its 20th anniversary this week, Birx wants to apply that model to rural health care in the U.S.

The 20% of Americans living in rural areas have fewer hospitals and doctors than those in urban areas. And for many, health care services are hundreds of miles away. In turn, the lives of rural Americans are, on average, shorter.

Cardiovascular disease and drug overdose are top causes of death in the U.S. and particularly problematic in rural areas. Both can be prevented with proper health care.

Birx talked with Baptist News Global about the success of the Bush program, the difficulty of COVID, and why rural care is critical for the health of the entire country. This interview is edited for length and clarity.

Why are you doing interviews specifically with faith publications such as BNG ahead of the PEPFAR anniversary?

Birx: I was working in Africa before PEPFAR. I started working there in 1998. I can’t tell you what it was like working there, knowing that you had life-saving medicine in the U.S. that was changing people’s lives from 1996 on, and then wheelbarrow-loads of individuals being carried to the hospital, and being turned away because there was no care for them.

There were religious groups like CMMB (Catholic Medical Mission Board) and other groups that had been providing technical assistance and program implementation overseas, yet were headquartered in the U.S. And then there were faith-based health care delivery systems in sub-Saharan Africa that had been established and working for more than a century. …

President Bush realized very early on that we had to have an integrated approach, that all the money couldn’t go through host governments. It had to go through organizations that already were established, that already had established trust in the community. And in many areas, those hospitals, those clinics were the lifeline for those communities.

When you’re dealing with a highly stigmatizing disease like HIV, having it within a trusted community, the faith-based community, makes a big difference. Through the years of that investment, we had some very thorny issues of trying to reach men. No matter where you are in the world, men are recalcitrant to health care delivery.

So, we started a program, a public-private partnership called MenStar. And they looked at different programs to how they were successful or not. And believe it or not, a lot of the programs that were grassroots outreach to men were faith organizations. … They listened to one person in their lives. Their moms. … And we knew where the moms were. We knew the moms over 40 were all in church on Sunday.

President George W. Bush (R) speaks on the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington DC. Also present are (from L-R) Jean William “Bill” Pape, “Aunt” Manyongo Mosima “Kuene” Tantoh and Bishop Paul Yowakim. (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

What a contrast to the ability to disseminate health care information during the COVID pandemic.

Yeah. When governors closed down institutions, you closed down one of the primary, trusted information delivery networks. The community centers weren’t open, and the churches weren’t open. … We knew who was vulnerable. It was people often over 60, over 65, and those with a lot of other underlying medical conditions. They Zoomed (religious services) while the younger generation could have been in person and carrying information back to their family members from the churches.

AIDS is in a different phase as a disease. What is the role of these faith-based organizations now?

They remain very important for service delivery and information and communication. … I think a lot can be learned from how we controlled HIV/AIDS without a vaccine, and how we aren’t controlling COVID with a vaccine. And I think it really shows that you have to do the hard work at the community level.

“A lot can be learned from how we controlled HIV/AIDS without a vaccine, and how we aren’t controlling COVID with a vaccine.”

I mean, let’s think about who is most at risk (of COVID), the people who are still in churches in the United States on Sunday or still have the relationship with churches. And I think by not utilizing that, we were not communicating information in a way where, particularly rural communities, can get information they can relate to.

In the many rural communities, there’s a dollar store and a church. There’s not a Walgreens, a CVS or a clinic. And of course, that is the way it is often in sub-Saharan Africa.

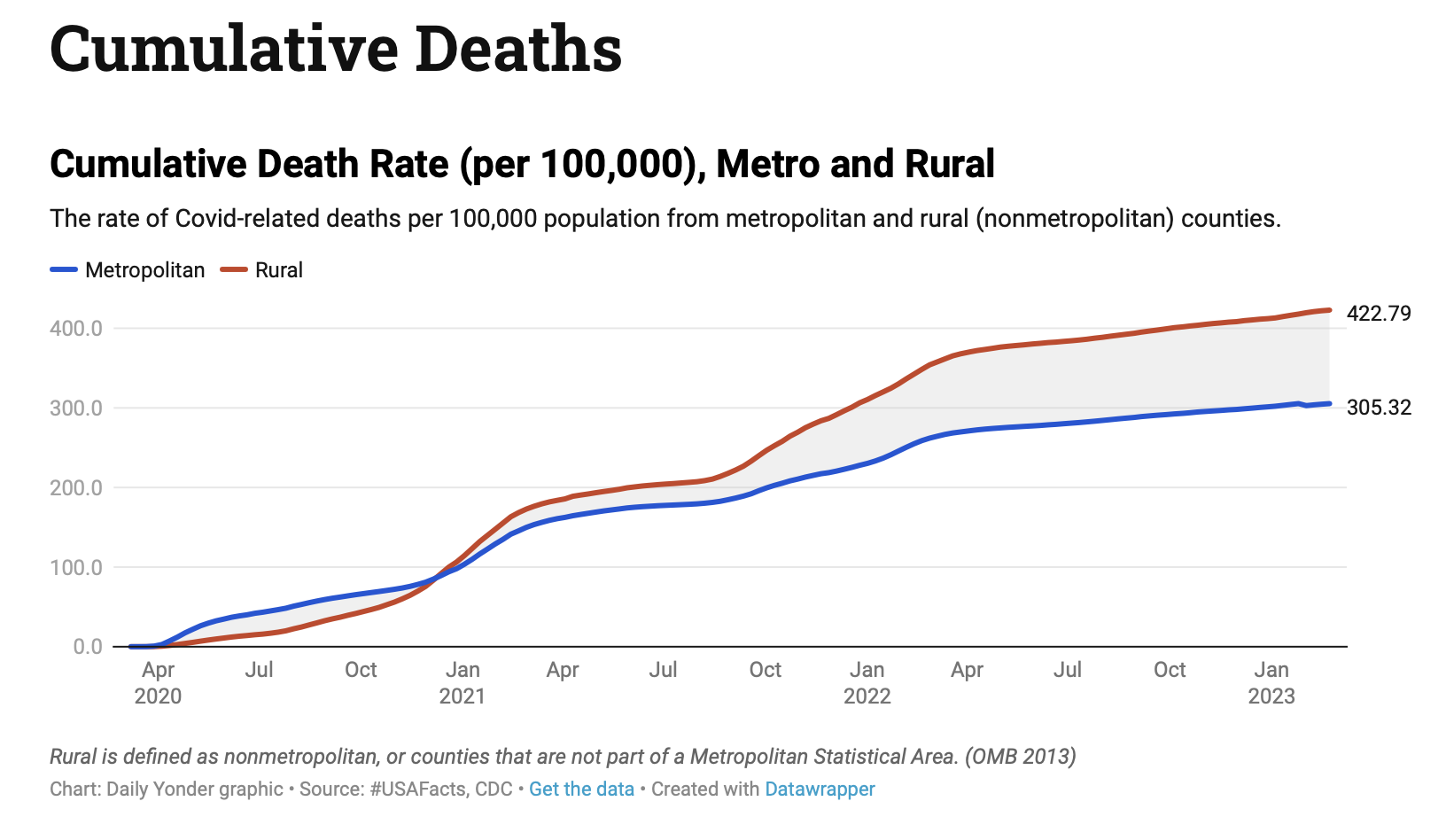

Source: Daily Yonder (https://dailyyonder.com/covid-19-dashboard-for-rural-america/)

In the U.S., our rural health care is weak and seems to only get weaker. And in sub-Saharan Africa that also was the case. Can you connect those dots?

So now you have defined my current passion. When I went out through the country, I went to rural areas as well as urban areas. I got to 44 states, and I got to the tribal lands. What struck me is rural health care in the United States was worse than what I had found in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Rural health care in the United States was worse than what I had found in sub-Saharan Africa.”

I had spent 20 years working to ensure everyone in a community has access to that lifesaving information, that they know about their risk to HIV, that they can get tested. And then I come back to a region where there are no clinics, no outreach, no engagement with the community. Half the community hospitals are closed, no primary care. The tribal lands were worse than the community I had served in Africa. And no one seemed to care.

And then they say, oh gosh, look, people in rural areas died at 20% higher rates than people in urban areas from COVID and started pointing fingers. They died because they didn’t have access and they haven’t had access. They’ve been dying at a higher rate of 20% greater than average long before COVID. …

I am absolutely committed to bringing those solutions back that we know work in rural areas. … It’s doable. We did it, we fixed it.

Ambassador Deborah Birx, M.D., Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Department of State, speaks at “Making AIDS History: A Roadmap for Ending the Epidemic” at the Hart Senate Building on June 14, 2017, in Washington, DC. (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

New infections in Africa are down on average 50%, but in some countries, 75%. Deaths are down by 90%. Now imagine if we did that. Imagine if we decrease opioid deaths by 90%. These are the things that are possible if you look at things differently.

Is this a policy issue, a money issue? What do we do?

I think people have given up. They look around and say nothing can be done. Well, I could tell you when a million people were dying a year in sub-Saharan Africa, everybody was looking away. And that was what was so spectacular about what President Bush did.

It’s going to take some resources, but not new resources. It’s a matter of programming our current federal dollars according to our population. What do I mean by that? If HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) committed 15% of their funds to rural health care innovation research delivery like we did in Africa, … if they committed 1% of their funds in the same way to the tribal nations, if SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) or substance and mental health groups did the same, there would be more than enough resources to fund these local organizations and churches to do outreach and deliver information. …

And then it can link you to telehealth. But telehealth without the wraparound community information and services is never going to be enough.

That’s the most hopeful thing I’ve heard anyone say about rural health.

I am on this 24/7 now. It’s been two years of trying to convince people there are solutions out there. These are models that are tried and true.

Africa was able to respond to COVID because of the infrastructure and the personnel and the church commitments that we had been funding. … It became the platform that responded to COVID, and there was no one there except the local communities. The international groups weren’t there, almost all of the expats left. …

And that’s why I know we can fix rural health, because everybody — Harvard and Yale — can leave and these communities can continue to thrive. To thrive and strive forward because they’re going to have the empowerment to actually deal with the issues they’re confronted with.

Related articles:

Mercer University dedicates new $50 million Medical School campus

As more Americans delay health care they can’t afford, it’s time for the church to be a light once again | Analysis by Rick Pidcock