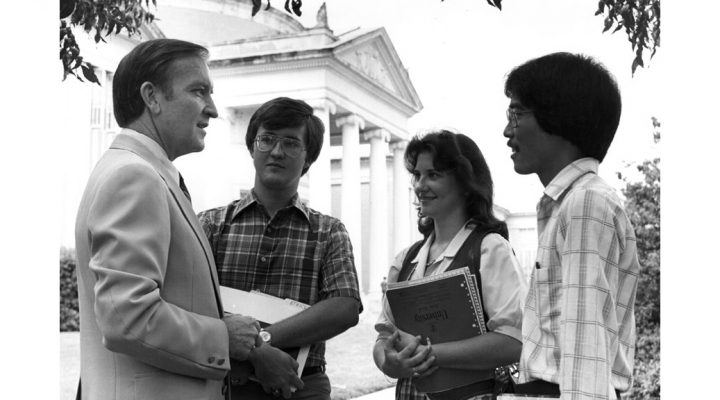

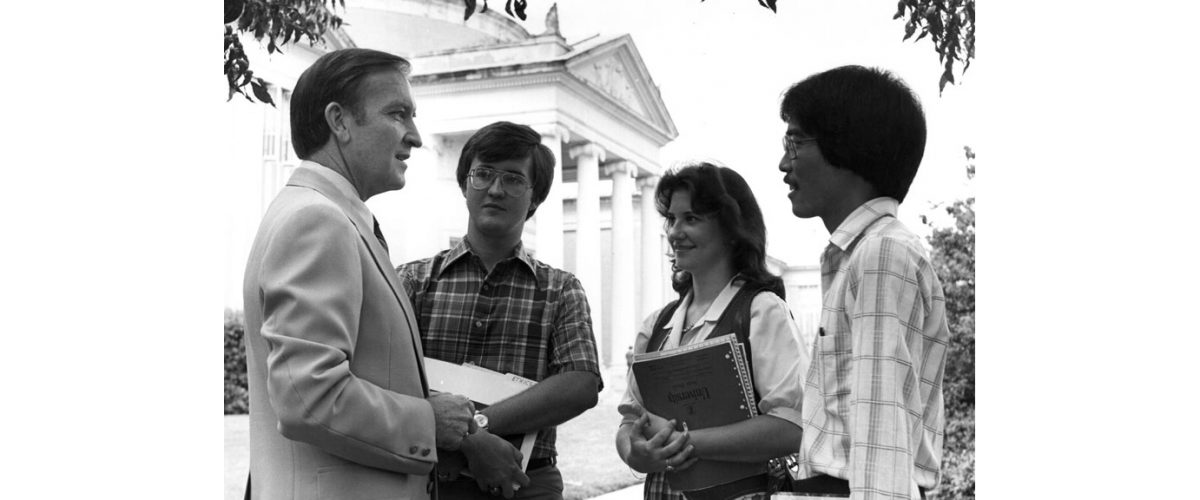

The president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary from 1978 to 1994, Russell Hooper Dilday, died June 21, at the age of 92. Under his leadership, Southwestern reached heights of enrollment and impact seen neither before nor after by a Southern Baptist seminary.

Dilday was preceded in death by his wife, Betty, and by his son, Robert. Please allow me to tell you a little about Russell Dilday from the perspective of one student, professor and pastor.

Malcolm Yarnell

In 1991, after I spent almost four years preparing intellectually and spiritually for full-time vocational Christian ministry, Russell Dilday acknowledged my completion of the master of divinity degree with biblical languages. During my student years at Southwestern, I had arrived at a different political position than Dilday regarding the controversy disrupting the Southern Baptist Convention. However, that difference in outlook never kept the president who handed me the degree from displaying his exemplary civility in Christian conduct.

In 1994, I watched from afar as Dilday was locked out of his own office and shown the exit to his beloved seminary. Like other Southern Baptists, I was shocked by this rough treatment yet impressed by his graceful dignity.

Over the next decade, while researching the experiential theology of Edgar Young Mullins, I also discovered Dilday’s thorough research into the theology of that previous denominational statesman. Dilday not only wrote about the apologetic legacy of Mullins; he continued his legacy as a statesman.

While I remain less individualistic than either Dilday or Mullins, I have come to appreciate the deep wisdom in their conservative religious personalism and their fervent advocacy of Baptist identity.

In 2005, I received a telephone call from the front desk of the Baptist college at Oxford University. It was Russell Dilday asking if I would mind being a host for him and several Texas Baptist dignitaries attending the centennial celebration of the Baptist World Alliance. Feeling quite honored, I rearranged my day, then gave Dilday’s group an overview of Baptist history in Great Britain. During our long conversation, I showed them several portraits of Baptist dignitaries and the death couch of William Carey, the founder of the modern missions movement. It was unusually hot in England that summer, and we Texans were suffering slightly from the British lack of air conditioning, yet these true Baptists were elated to learn more about their own heritage.

The group sought to present me an honorarium. I refused, noting my pleasure at deepening my fellowship with Dilday and coming to know each of them. However, the former president of Southwestern gently forced the honorarium into my hand, winked at me, and said, “Malcolm, you forget that I know how little you faculty earn. Receive this as a gift from the Lord and from me as a token of our appreciation for your continuing service to all Southern Baptists.”

He then smiled, gripped my hand firmly, and walked away before I could raise an objection. Again, I was struck by his exemplary graciousness.

“While we might have differed by degrees over anthropology and bibliology, we both swam in the same great tradition of Baptist life.”

Through the following years, I came to realize the import of his parting words for me as one of the few theologians who continued the Southwestern tradition of theology at Southwestern Seminary. While we might have differed by degrees over anthropology and bibliology, we both swam in the same great tradition of Baptist life in Texas, in the Southern Baptist Convention, and in the Baptist World Alliance.

Moreover, I came to lament with him certain “low points in the SBC odyssey.” Dilday summarized these low points as “forced uniformity, political coercion and egotistic self-interest.”

In 2020, at the funeral service of professor James Leo Garrett Jr., I reflected publicly on my theological mentor’s legacy with both former teachers and current colleagues. Before the proceedings, the visibly declining Dilday again addressed me personally, shook my hand and thanked me for my faculty service. For those who are not quite aware of how significant that is, please understand that he engaged me graciously before and after momentous events in his life, in our seminary’s life, and in our denomination’s life. Through each encounter, he showed Christian civility: during a controversy, after he was summarily dismissed, and after many years of watching me actively advocate my own theology.

Russell Dilday affirmed the calling of Baptist students, professors and pastors, no matter which side of the aisle they occupied.

As a lifelong advocate of biblical inerrancy, as a current pastor in a Texas Baptist church and as a current faculty member of his former seminary, I am convinced the way forward for all Southern Baptists must be to heed Dilday’s final challenge. In Higher Ground: A Call for Christian Civility, the sixth president of Southwestern Seminary wrote, “So the best way forward from this quarter century of strife is to let the past convict us and work to restore a gentler, kinder tone in our discourse and deliberations —in short, a return to Christian civility. That’s the road to higher ground.”

Russell Dilday was in his personal character what he advocated in his public proclamations. Rest in peace, dear brother in Christ and father in Christian ministry. You have reminded Southern Baptists and Baptists in Texas what it means to be like Jesus. May our Lord speak to you even now the words you longed to hear throughout your meaningful life of often painful service: “Well done, good and faithful servant! You were faithful over a few things; I will put you in charge of many things. Share your master’s joy!”

Malcolm Yarnell serves as teaching pastor at Lakeside Baptist Church in Granbury, Texas, and as research professor of theology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Related article:

Russell Dilday, Baptist statesman